Paper (紙, kami), alongside the compass, gunpowder and printing press, is one of the four great discoveries of China. Many sources state that paper first appeared in 105 C.E as an invention of a Chinese official Cai Lun (蔡倫, 50 C.E. – 121). This is however incorrect, as numerous archaeological sources prove that paper existed as early as the middle of the 3rd century B.C. Excavated sutras from the end of the Zhou dynasty (周朝, 1046 – 256 B.C.) are considered to be the first works written on paper. Cai Lun however greatly contributed to the improvement of paper production technique.

The left radical (糸, ito, “a thread”) of the Chinese character for paper (紙) indicates usage of silk floss in its production at early stages. This is why the first paper was very different from its later forms, as it was not produced purely out of plant fiber. Consequently, it was costly, and also due to a hard and slippery surface and weak absorption, it was not very suitable for writing.

In later stages paper ingredients included tree bark, fabric scraps and fishnets (technology introduced by above mentioned Cai Lun). It was the dawn of the modern paper that is being used in calligraphy today, known as Xuan paper (宣紙) which was invented around the 8th century during Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907). After the fall of the Han dynasty (漢朝, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.) paper manufacturing technology and therefore its quality were improving. It was produced out of all kinds of materials, including bamboo, wisteria tree bark, etc. Xuan paper is well known for its spectacular longevity and strength, as well as outstanding ink blur ability.

The art of making paper in Japan was initiated by a Korean monk in 610 C.E., who brought the recipe with him. From this period, the popularity of the art of calligraphy grew rapidly. During the Edo period (江戸, 1603 – 1867) paper production duty was the shogunate‘s (将軍, shogun – “leader of the army”) main source of revenue.

Japanese paper (和紙, washi) has slightly different characteristics than Xuan paper as it is produced out of different plant fiber and different water. Aside from calligraphy its numerous forms are applied in everyday life, such as interior design, or other arts (折り紙, origami).

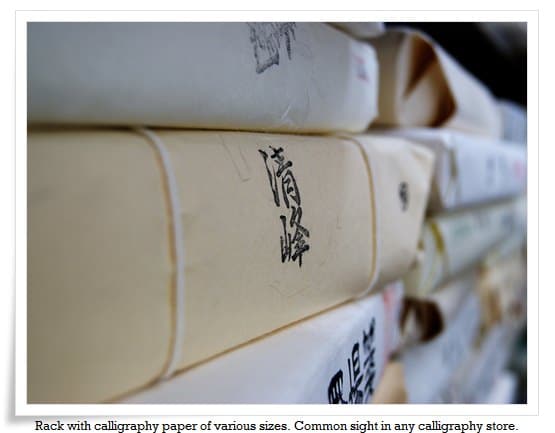

The difference in paper ingredients is not the only factor that separates Xuan paper and washi. For instance, Japanese paper used for writing kana (かな) called Kana Ryoshi is often lavishly decorated with gold flakes, silver powder, floral patterns, different colour shading (雲紙 kumogami, so called “cloud paper”), and often has ink mixed into the paper pulp, which creates various smudge effects. Some sheets are even perfumed. Modern paper types are virtually infinite.

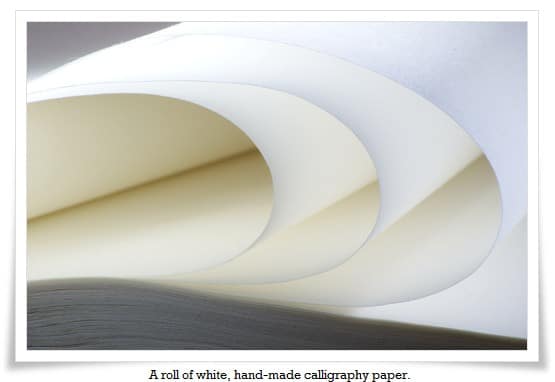

Despite the differences, Chinese and Japanese paper types have a lot in common. They not only absorb ink very well, but seem to do the same with light. Western paper is coated and slippery to the touch, and usually hard and stiff. Calligraphy paper is warm, fuzzy, and has an irregular surface that seems to absorb light, storing it as universal energy. While writing, all that power is mixed with ink producing various spectacular blurring effects and fascinating lines. Finally, Xuan paper and washi are mostly handmade. Each sheet, even from the same factory, has unique patterns and characteristic irregular watermarks that define its natural beauty. Similarly to calligraphy, they cannot be copied or reproduced.