Today ink comes in two major types: hardened (固形墨, kokeiboku) and liquid (墨汁, bokujuu). The latter one is mainly a domain of Japan, and it is chemical based. Washable ink was even developed for children practicing shuuji (習字, lit. “studying characters”) at school.

It is said that the best quality ink is hardened, made of pine soot (松煙墨, shouen boku), young deer horn glue and preserving perfume. Pine soot ink produces multiple layers of enchanting light-black shading. They overlap each other on paper, and create an unforgettable monochromatic blurred mosaic of splashes and lines. Since the second ingredient is extremely rare, other animal based glue (mostly cow hides in Japan and fish bones in China) is used. Pine soot ink is usually more expensive and rather troublesome to manufacture, and so cheaper ink made of oil lampblack (油煙墨, yuen boku) is more common today.

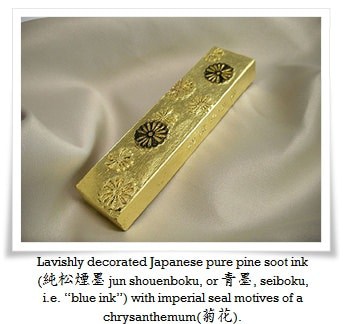

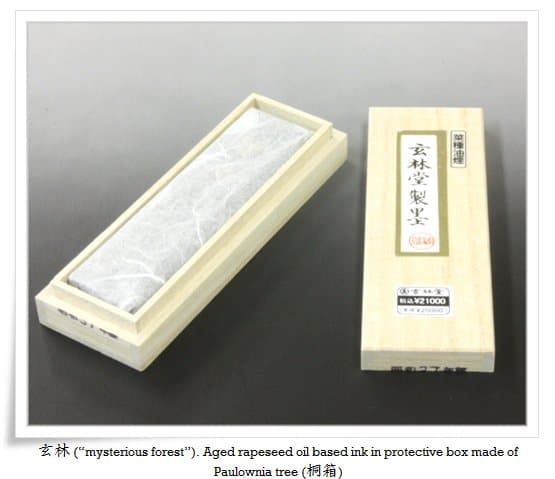

Ink is often decorated with motifs, or comes with engravings disclosing the manufacturer, ink name, etc. Better quality ink is sold in protective boxes usually made from Paulownia tree (桐箱, kiribako).

Liquid ink is of an inferior quality and it does not face the passage of time as well as hardened ink. Also, the entire concept of a “ready-made product” goes against the spirituality of calligraphy. For those and other reasons serious calligraphers will never even consider using liquid ink, even for studying purposes.

Hardened ink comes in various shapes and colours. The bigger ink sticks (20cm long) are mainly used for ink making machines (墨すり機, sumisuriki), whenever large quantities of ink are needed for big scale works.

Other than black ink, there is gold (金墨, kinboku), silver (銀墨, ginboku), red (朱墨, shuboku), various shades of brown-ish grey (茶墨, chaboku), or even violet (紫墨, shiboku), etc. Naturally, coloured ink is rarely used in calligraphy, with exceptions of special instances. Ink painting (墨絵, sumi-e) artists often apply coloured ink in their works. Light coloured ink is popular among Japanese kana (かな) calligraphers, too.