Japanese mandalas are typically graphic visualizations of scenes described in a particular Sūtra. The most known examples are probably the Kongōkai (Diamond) and Taizōkai (Womb) mandalas introduced in Japan by the monk Kūkai (空海 774~835) in the Heian period.

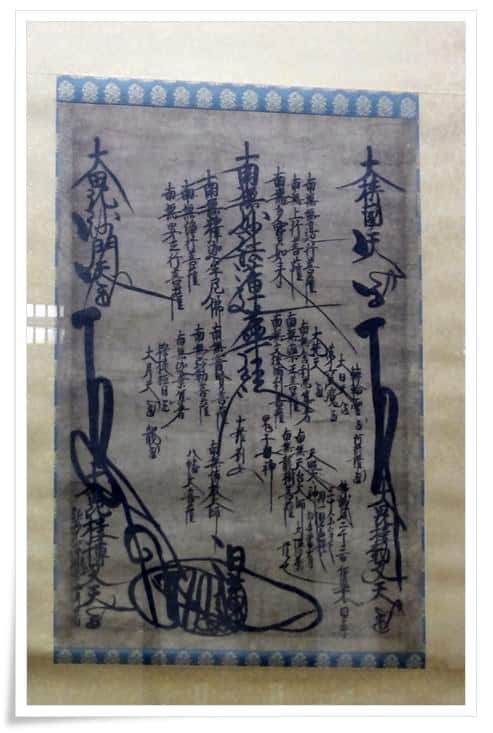

Inscription date: 21st day, 4th month, 1st of Kan (1278) Size: 924 ×

458 mm (3 sheets)

Recipient: Ubasoku Nissen (優婆塞日専)

The calligraphic mandala, known as Moji-Mandala, conceived by the monk Nichiren (日蓮 1222~1282), equally describes a specific scene contained in a Sūtra, the Lotus in this case. The Moji-Mandala, however, is inscribed by making use of logographs only, without any other form of figurative painting or decorative pattern. Nichiren is certainly not known for being a calligraphic virtuoso, yet his Moji-Mandala presents a few interesting characteristics, worthy of being mentioned in this context.

The inscriptions in the classic moji-mandala consist of Chinese characters and medieval Siddham script representing elements of the Buddha’s enlightenment, protective Buddhist deities and certain Buddhist concepts whose appearance may otherwise vary depending on the particular school and other factors. The Siddham characters descend from the Brahmin script. The name Siddham comes from Sanskrit meaning accomplished or perfected. Kūkai introduced it to Japan in 806 C.E. after he studied Sanskrit and Vajrayana or Mantrayana Buddhism in China.

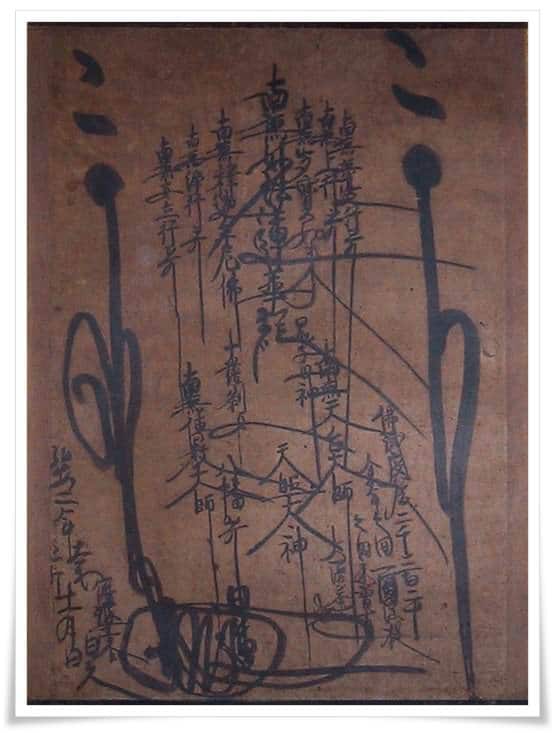

Inscription date: 11th month, 2nd year of Kan (1279)

Size: 451 × 300 mm (1 sheet)

Recipient: Ubasoku Nichiku (優婆塞日久)

Bestowed upon Izu Egawa Yoshihisa (伊豆 江川吉久)

In Japan, Siddham is mainly known as Bonji. The script was used for writing mantras and copying Sutras in the Shingon and Tendai Esoteric Buddhist schools as well as in Shūgendo syncretistic teachings. The use of Siddham later vanished in other areas. The sutras introduced from India to China were written in a variety of scripts, but Siddham was the most important. During the period in which Kūkai mastered this script, the trading and pilgrimage routes to India over the Silk Road, were closed by the expanding empire of the Abbasids. When China tried to eliminate Buddhism, considered a threatening foreign religion, around the middle of the 9th century C.E., Japan was cut off from the primary sources of Siddham texts. During the same period in India, Siddham was replaced by other scripts such as the Devanagari.

Ironically, Japan remained the only place which preserved Siddham, even though solely for writing mantras and copying sutras. Although Siddham became de facto a langue morte, it was influential in the development of the Japanese kana writing system attributed to Kūkai. While the shapes of kana derive from Chinese characters, the principle of a syllable-based script and their systematic ordering was borrowed from Siddham.

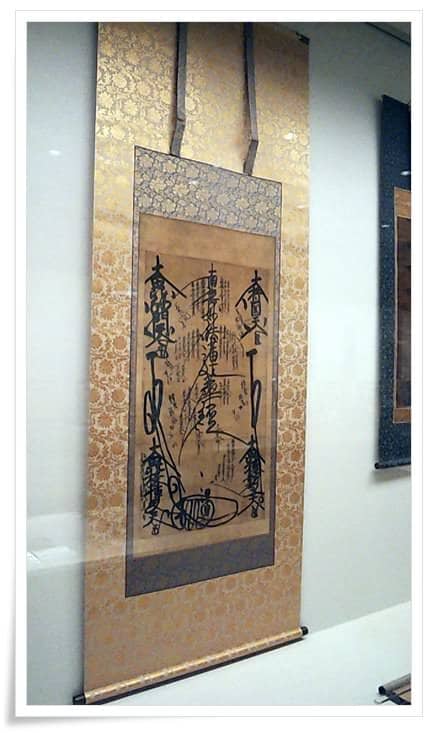

Inscription date: 8th month, first year of Kan (1278)

Size: 955 × 530 mm (3 sheets)

The mythological scene which Nichiren depicted on his mandala is described as the “Ceremony of the Air” symbolizing enlightenment. In classic Lotus iconography the two Buddhas, Śākyamuni and Tahō (Many Jewels), are placed within a huge stupa surrounded by a great assembly of Bodhisattvas, Saints, Deities and so on.

Nichiren substituted the stupa with the seven characters of Na-Mu-Myō-Hō_Ren-Ge-Kyō (Devotion to the Mystic Law of the Lotus Teaching) and inscribed the figures on different spatial levels in a way that, by facing the mandala, one would be actually “looking at the assembly.”

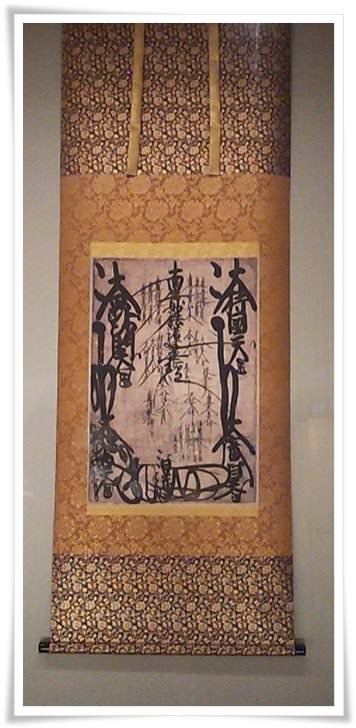

Inscription date: 4th month, 3rd year of Kan (1280)

Size: 618 × 409 mm (1 sheet)

From the point of view of calligraphy, there are perhaps two interesting aspects. One is the rendering in graphic form of one of the so-called 32 physical features of the Buddha, which is the “Pure and far reaching voice”. Nichiren chose to represent the Buddha’s voice by inscribing the characters using elongated spikes known as kōmyō (光明), usually translated as “rays of light”. This method of visualization is particularly relevant because instead of typical static butsu-ga imagery, these kōmyō spikes, representing the Buddha’s voice, would enable the devotee to be projected inside the mythological scene as described in the Lotus Sūtra, listening to Śākyamuni or performing devotional rituals with all those figures present at the event.

In the course of the centuries, these kōmyō inscriptions have been institutionalized so that all later abbots in the Nichiren tradition would inscribe the Moji-Mandala using the same particular calligraphic traits.

Another area of interest is the signature on the mandala, known as kaō (花押), literally “imprinted flower” A kaō seal is a stylized signature or mark. It first appeared in China during the Tang Dynasty (618~907) and was introduced in Japan during the Heian period. Although its popularity faded after the 15th and 16th centuries, it is still used among contemporary politicians, famous individuals, and of course, the Buddhist clergy. The reading of an individual kaō often requires advanced knowledge, and exhaustive literature is devoted to this topic.

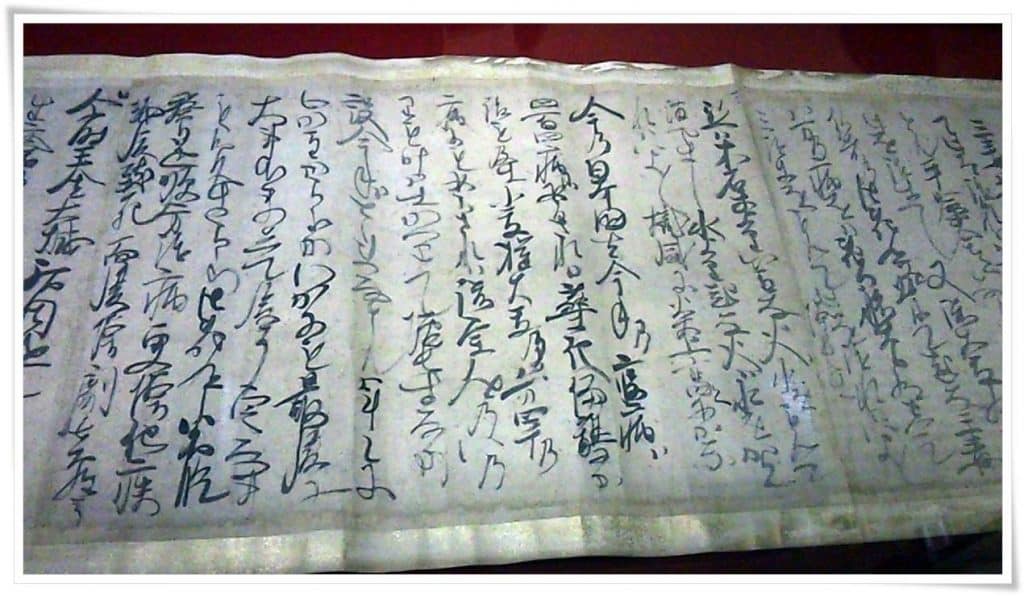

Called the Nakatsukasa Saemonj dono gohenji (中務左衛門尉殿御返事),

size: 318 × 2900 mm

The recipient was a samurai named

Nakatsukasa Saemon-no-j Yorimoto (_中務三郎左衛門尉頼基)

best known as Shij King.

Nichiren would place his kaō signature thick and bold at the bottom of his mandala. As the kaō seal is written in cursive script, it is difficult for others to copy. Nichiren did also conceal Siddham characters in his own seal, called kao. In the Bun’ei, Kenji and Koan periods, these three elements have changed significantly. Until the 5th or 6th month of 1278, he based his kaō on the root character vam. During the summer of that year, he changed it to bhrum.

Size: 315 × 11210mm, Size: 296 × 197mm.

As an additional note, it is worth mentioning that the moji-mandala is not Nichiren’s exclusive invention. Besides the Lotus mandalas inscribed in Siddham characters and adorned by decorative elements, the monk Shinran (親鸞 1173~1263) drew a mandala of six characters based upon the invocation of the Buddha Amida. The format was also a hanging scroll inscribed vertically. Quotations from the Amidakyō and from the “Pure Land treatise” of Vasubandhu, written on different sheets of paper were pasted to complete the mandala. Someone else usually added a lotus dais at the base of the central inscription. As in Nichiren’s case, these moji-mandalas were easily accessible objects of worship, compared to statues or elaborate paintings.

To purchase “The Mandala in Nichiren Buddhism volumes” please visit the The Nichiren Mandala Study Workshop – store.

All Photos and text is © The Nichiren Mandala Study Workshop

Commentary about images:

1. Mandala inscribed by Nichiren

Inscription date: 21st day, 4th month, 1st of Kan (1278) Size: 924 × 458 mm (3 sheets)

Recipient: Ubasoku Nissen (優婆塞日専)

Nissen is the believer’s name, usually a combination of the actual name with “nichi”. Ubasoku is the Japanese transliteration for the Sanskrit word “Upasaka”, literally “attendant”, but in a broader sense, indicating a lay person who had taken certain vows.

Location: Gusokuzan Ryuhon-ji temple in Kyoto.

2. Mandala inscribed by Nichiren

Inscription date: 11th month, 2nd year of Kan (1279)

Size: 451 × 300 mm (1 sheet)

Recipient: Ubasoku Nichiku (優婆塞日久)

Bestowed upon Izu Egawa Yoshihisa (伊豆 江川吉久), a lay follower. As observed in many cases the nichig is composed with a part of the actual name. The last character of Yoshihisa can also be read ku.

Location: Rissho Ankoku-kai, Chiba

3. Mandala inscribed by Nichiren

Inscription date: 8th month, first year of Kan (1278)

Size: 955 × 530 mm (3 sheets)

Location: Honno-ji temple, Kyoto

4. Mandala inscribed by Nichiren

Inscription date: 4th month, 3rd year of Kan (1280)

Size: 618 × 409 mm (1 sheet)

Location: Minobusan Kuon-ji temple, Yamanashi

This mandala was previously in possession of the Hon’ami clan, after it came into the ownership of Hon’ami Ksa (本阿弥光瑳), an adopted child of the famous Honami Ketsu (本阿弥光悦 1558~1637), a craftsman, potter, lacquerer, and calligrapher who started his work under the patronage of Tokugawa Ieyasu. He was a devout follower of Nichiren’s Buddhism, and his retreat was used for prayer meetings, in addition to its function as an artist gathering. This Gohonzon is the only one housed at Minobusan Kuon-ji since all the other scrolls were lost in the great Meiji fire. Mrs. Kaji Sakiko donated the Gohonzon to Kuon-ji in 1933.

The scroll was recently restored, and unfortunately, much of the original antique patina has been removed, and the results are not of good quality.

5. Original holograph by Nichiren

Called the Nakatsukasa Saemonj dono gohenji (中務左衛門尉殿御返事), in English, “The two Kinds of Illness”. One of the few original letters that are complete in their original form. It is composed of six sheets mounted on a scroll measuring 318 × 2900 mm in total. The recipient was a samurai named Nakatsukasa Saemon-no-j Yorimoto (_中務三郎左衛門尉頼基) best known as Shij King.

Location: Gusokuzan Ryuhon-ji temple in Kyoto

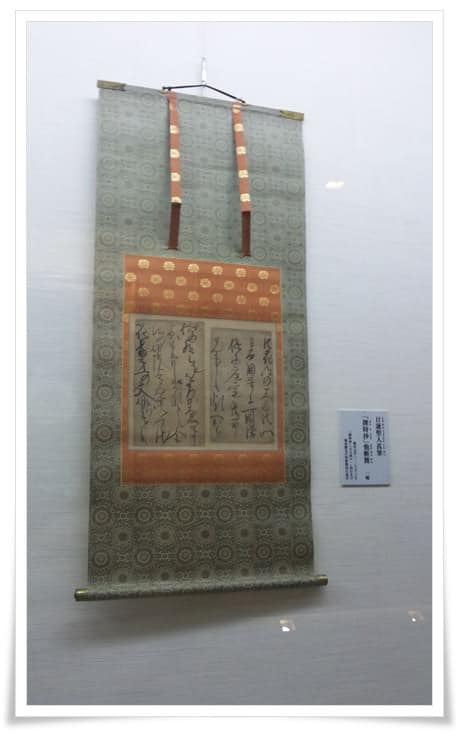

6. Original holograph by Nichiren:

Two fragments of Nichiren’s letter to the Ikegami brothers, known in English as “Letter to the Brothers” (兄弟抄). Portions of the letter kept at Ikegami Honmon-ji are the sheets 4~13 and 17~32. One scroll is mm 315 × 11210, while another sheet is mm 296 × 197. Other fragments are stored in Kyoto, Ishikawa, Yamanashi, while another part is privately owned.