My own involvement in this special art has a haunting and evasive, sometimes very simple, undertone. Haunting because it is part of my mental life that includes much that is beyond or not part of everyday rational habits. It is more than an exotic Asian mystery and philosophy felt as a special mystique by many Westerners, and it is more than skilled performance, more than a craft, and more than simple language in the service of its content.

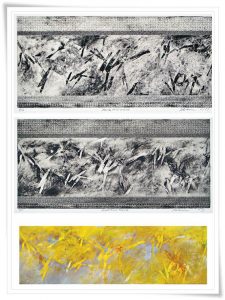

Art: Goldwalk-5×7 card

The complex and special Chinese characters, largely historically based in images, combines with Japanese with its own Kana glyphs, a visual, sound-language syllabary, an “alphabet” of a limited number of characters, giving us a realm very different from our 26 abstract, Latin alphabet characters and its ten Arabic numerals. This, of course, also has a rich historical development from image-based signs; but that is left well behind and is little known or felt in Western written or printed language. The Western language also has a sound-expressive life in poetry and song, with the help of musicians and their scores and symbols. The Western written forms are basically abstract and work efficiently with mathematical symbols and functions. Both Eastern and Western writing have traditions of beautifully crafted writing.

I am not trying to conduct a comparison of Eastern and Western calligraphy, so this is all now in reference to the Chinese and Japanese realm. The Four Treasures of the calligrapher, of course, are paper, brush, ink and inkstone.

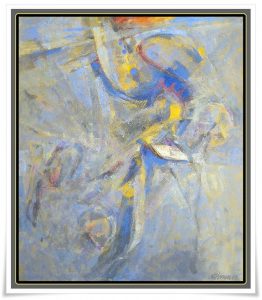

Art: Gears

So, what is the haunting mystery? I think of it as a 5th Treasure or dimension of calligraphy that is the silent experience itself. Questioning, some half century ago, how one should or might initiate one’s learning in the pursuit of visual art and calligraphy, Saburo Hasegawa Sensei, instead of referring me to a book of design rules or principles, told me to spend time at night contemplating and viewing the stars. And it is there, or much of it is: space, our ever-present format, all the known gestalts of design: similarity, continuity, grouping, and closure, which is our sensory preference for ‘simplest available’ structures or shapes. There is much more that transcends rules and abstract reasoning: the felt quality of dark and light, of tangible energy density, even color in the blue, red and yellow hints in the star’s and planet’s light. Space itself is a tangible mystery-here crowded and sparkly and there dark and deep, nearly obscured, empty, silent. And scale; we are in that space and sense its complex simplicity all without words or other abstract aids. Being in it, we lose ourselves and our worldly concerns if we give it a bit of time, more than the split seconds it takes to read a character or the 17 seconds average a viewer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art views a masterpiece.

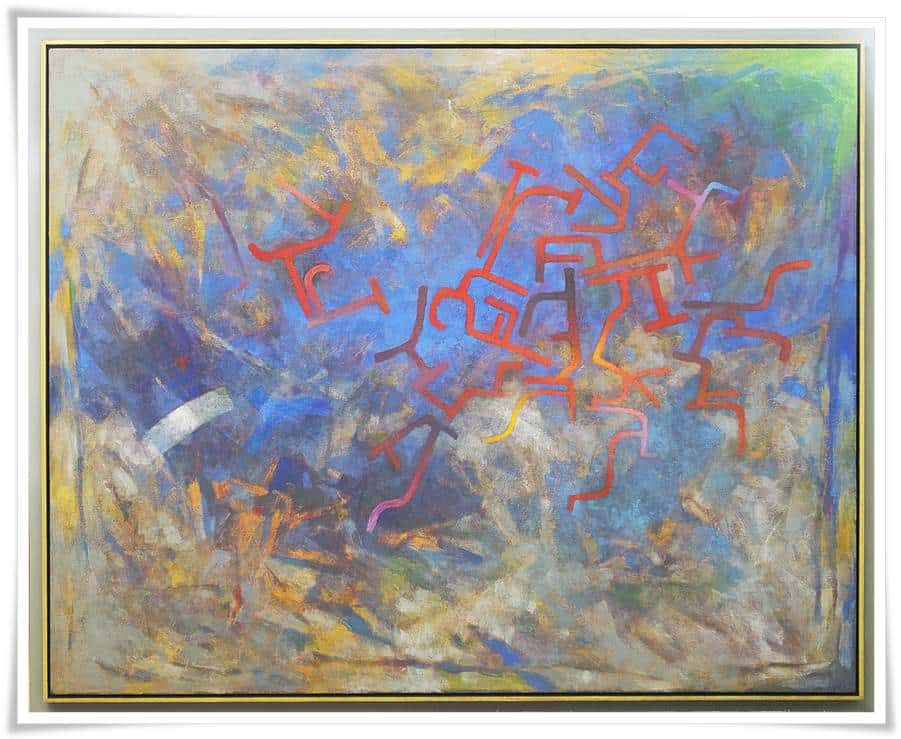

Art: Jaderitek

Something of this is possible in the calligraphy experience. In practice it is a going into the space, beyond the surface of the paper with the brush and its night-space ink, in fluid density, slowly or in haste, with power or gentle movement. There is a texture of feeling and a special kind of knowing in that doing. And in viewing a finished work one can access it all, even if one’s own craft of execution is wanting. In learning to see and then write a character there is a subtle enterprise in what I think of as ‘energy rehearsal’. In learning to write a new character there is a really rigorous inner struggle to first, comprehend what is actually there, then, in response, to imagine and rehearse that kinetic event, the act of writing. Not only the paper, ink and brush have to be prepared but one’s inner capabilities. We have to go beyond what is seen, the model character, and here, for me at least, rules have to be forgotten and the space-movement-configuration realized as one event to be released into being. One’s sensibility is in charge, for better or worse.

Art: Meander

Then, open to calligraphers and viewers alike, is the work itself. For it to be realized, really perceived, requires that same sort of effort of going mentally and imaginatively into its space and time. If the glyph is in fact a known “word”, its literal meaning is invoked and becomes part of the experience. If it is “abstract”, then one is free to discover its immediate, intrinsic meaning as one’s own experience. The point is that, as literal or abstract an image may be, as one’s own inner experience it is significant beyond its literal sign function or, absent a signed meaning, in how one takes it in, following its movements, configurations and other qualities. And that is qualified, i.e., given its unique substance by everything involved: the texture, color and density of ink, quality of paper or other surface, its scale, energy and format including presentation, mounting, velocity and contextual relationship to previously known works. And, if realized, this is my 5th dimension of calligraphy: an experience beyond the concerns of all else, even craft and technique, that fills up the time and space of our daily world .

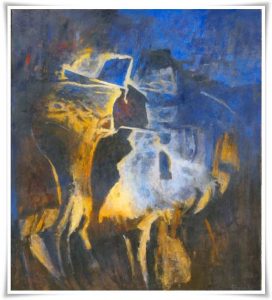

Art: October Dance

As the lesson of gazing at stars instructs one’s sensibility, the study and appreciation of good calligraphy modifies the inner life-form sensibilities that govern the creation of any visual art. It is one source of the artist’s creative knowing that transcends learning a set of mechanical rules or even trying to faithfully reproduce a masterpiece. A masterpiece performed freely is not a mechanically processed reproduction, a document. When a character is truly perceived and internalized one can then perform it – or some other work and even be ‘not conscious’ of the rule/model.

In a wonderful new book, “The World Encyclopedia of Calligraphy“, is stated this, to a westerner, off-putting fact:

…to become truly adept one must spend years mastering the forms of one’s models.”

And this:

…students must spend years simply memorizing them.”

(the thousands of Chinese characters). I submit that, while true for those who would indeed master the entire language, this is something that can be gotten “Beyond”. One’s intention may well be a kind of simple, yet rewarding and even transcending experience through the study and practice of calligraphy. The fact that a single character can become the focus of a very challenging and rewarding experience should relieve the fear of being ignorant of all of them. One sees, then perceives beyond the mechanics of “seeing”, then forgets, goes to blankness, emptiness, then assembles in ones’ own internal working space all that needs to be realized in the four dimensional space of sho. Show?. The Westerner’s awe of Oriental “otherness” needs to be gotten Beyond; and this can be done in accepting, not fearing; in acting simply to take in, forget and ‘reassemble-act-out’ with the warm and friendly means of the Four Treasures. One’s own 5th Dimension.

Art: White Drift