Monstrous snake-like hulks, scales reflecting memories of the mighty skies, massive mouths armed in rows of razor sharp teeth, and sometimes even wings….. by now your mind has surely conjured familiar images of a creature that lurks in oft’ forgotten myths of both East and West. The word “dragon”, in most European languages, has as its origin the Greek word “draken”, meaning “sharp-eyed” (English: “dragon”, German: “drache”, etc.). The modern Chinese character 龍 (pinyin: lóng, i.e. “dragon”) was originally a pictograph of a beast with a snake’s body and a head with horns.

Whether in Europe or Asia, from ancient times to the present, a myriad of interpretations of dragons were crafted. What is interesting is that in spite of differences between East and West in the images of a dragon (A Western dragon was often associated with evil and ferocity, whereas an Asian dragon was characterized as wise and benevolent.), some features and attributed powers seem to be similar in both the East and the West.

|  |

|  |

The dragon, like the snake, is associated with the water element. It is a symbol of authority, power, the sun, a symbol of kings and emperors, just as the western image of the eagle and lion is an allegory of wisdom, knowledge, vigilance and watchfulness. A dragon spitting fire might depict summer.

During the Middle Ages, it was common to see a dragon interwoven into a design of crests displayed on the armour of knights or painted directly onto their shields. On helmets, the dragon represented bravery and the spirit or war, and its coiled muscular tail symbolised strength and energy. A dragon shown biting its tail depicted eternal motion, cyclicality and renewal.

|  |  |

According to ancient Chinese beliefs, the dragon is a guardian of primordial mysteries, an entity that links Heaven and Earth, an invisible beast roaming freely among its own chosen realms. To read more about Chinese dragons, please refer to the Beyond Calligraphy article entitled “Nine Sons of the Dragon King”.

Dragons appear in mythology all over the world, including Greek mythology, where, similar to gryphons, their role is that of guardian. It was none other than Christian ideology that has given dragons a negative image, equating them with the devil, synonymous with evil, sin, chaos, pagan beliefs, and heresy. However, the main purpose of this article is not to discuss the mythology of dragons, but to describe my recent ink painting (墨絵, すみえ, sumi-e) of nine dragons, from conception to process to completion.

|  |

Prior to commencing painting, an artist creates an image of what he or she intends to paint in their mind. The image is then transformed from the artist’s imagination onto the paper or canvas. Usually, in traditional European painting, an artist begins with a preliminary sketch. However, the paper used for calligraphy and the tenets of Chinese or Japanese ink painting art do not allow for this preparatory stage. This means that what you see in the pictures embedded in this article, was created without any corrections or changes, additions or painting over. Ink painting is defined by spiritual momentum and the “one stroke, one touch” method. Any mistake means that the entire work has to be discarded and begun again.

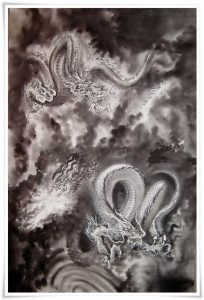

The main concept of the paintings was to depict the five elements (五大, ごだい, godai) of Buddhist philosophy, namely: Earth (地, ち, chi), Water (水, すい, sui), Fire (火, か, ka), Wind (風, ふう, fū), and (possibly the most difficult to present) the Void (空, くう, kū), an element that represents creative energy and the ability to communicate.

|  |  |

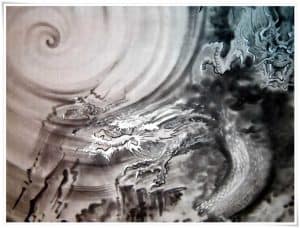

I began the painting with the dragon that symbolises the Water element. His body levitates, floating on waves with water springing from his mouth. He also holds a pearl in his paw. Next, I painted the dragon that you can see in the bottom-left side of the painting, the one that is resting firmly on a rock, symbolising the Earth element above which I incorporated the Wind element, represented by the turbulent clouds. At the very top of the painting you will notice a dragon with fire exploding from its open mouth, clearly defining the Fire element. Its massive body somewhat dissipates into the fury of smoke-like clouds not defined by any contours.

The last of the five elements I placed at the very top of the painting. My intention was that it represents the most distinguished and largest of all of the beasts on the scroll. I wanted it to dominate the other elements, guarding the Void element with its whip-like flexible body, ready to spring out in one fast surprising strike, like a viper striking its victim.

|  |

The painting itself was created quite spontaneously. I allowed the dragons to coil freely in the distant realm of mystical clouds and vapour. At some point I realised that I did not really need to emphasise the fifth element of ether, it seemed to paint itself. The entire scroll was infused with movement and energy, the element so elusive, yet so clear. Whether or not my observations are correct, I shall leave to your judgement.

I must say, the painting of this particular scroll gave to me great pleasure. There were, however, two incidents that nearly caused my heart to jump out of my mouth. The scroll was painted on the floor. At one stage, I was crossing over to its other side and slipped while carrying in my hand an ink-stone (硯, すずり, suzuri) filled with freshly ground ink (墨, すみ, sumi). I lost my balance and accidentally stepped onto the wet paper. Miraculously, I didn’t tear the work, even though I landed with my elbow in the middle of one of the dragons, and the majority of the ink spilled onto the floor. My blood rushed into my head, and I have never felt so warm during the winter season.

The second drama took place when my two and a half year old son, who had patiently waited for his moment of fun with “the dragons that daddy painted”, ran straight onto the paper and then fell down when the paper slipped from beneath his feet. The painting moved together with him about 1.5 meters. Luckily, the work was dry at the time, and nothing happened. The dragons clearly wished to remain painted and stood their ground.

After I finished painting with ink, I considered adding colour to my work but then abandoned this idea. Calligraphy ink has such a rich range of greys that it was truly not necessary. Nonetheless, I applied white paint, called titan white, to emphasise the meandering serpent-like bodies of dragons, as well as to redirect the patches of light, an element that I felt was missing. Work on the scroll was not easy due to its significant size. The entire work is 2.5 meters long and 65 cm wide. Traditional materials of sumi-e, i.e. water, ink, and calligraphy paper, were used. The only Western accent was the above mentioned white watercolour paint.

The inspiration for the scroll came from various legends about dragons, both Eastern and Western, and the unforgettable painting that haunts my mind ever since laying eyes upon the outstanding Nine Dragons Scroll (九龍圖卷, pinyin: Jiǔ long tú juǎn) by Chinese artist Chen Rong (陳容; pinyin: Chén Róng, ca. 1200–1266 C.E.) of the Southern Song dynasty (南宋, 1127–1279). The intention of this work was to show how a Western artist might approach a traditional Asian subject – a dragon motif. As the artist, all that I can hope for is that this painting will satisfy your aesthetic needs and please your soul, even if it is only for a split second. This work opened my inner eyes and made me realise the infinite possibilities of Far Eastern ink painting.

Copyright (c) 2012 Beyond Calligraphy & Mariusz Szmerdt. All rights reserved.

Original text, art and photography: Mariusz Szmerdt

English translation: Ponte Ryuurui (品天龍涙)

English editing: Rona Conti