History of the hanging scroll.

The hanging scroll is an art of its own, although it does not exist without the calligraphy work. It is said that the beauty of calligraphy depends on the brush work, ink application, character structure, composition, and rhythm. But equally important factors are the signature and the seal, the quality of framing, the display location, and even the time it is presented to the world (season, occasion, etc.).

The history of scroll making goes back to the Northern Song dynasty of China (北宋, 960 – 1127). Initially scrolls were hung in temples (and later on in houses) and used for religious purposes, mainly for worshipping Buddha. In time, being easy to carry from place to place, rolled up in a light wooden box called 桐箱 (Japanese: きりばこ, kiribako, i.e. a box made of Paulownia tree”), hanging scrolls became quite popular. First hanging scrolls presented calligraphy of Buddhist phrases, images of the Buddha, or ink-paintings related to the Buddhist tradition.

Kakejiku (掛け軸, かけじく, i.e. “a hanging scroll”) was introduced to Japan during the late Kamakura period (鎌倉時代, 1185-1333). Nonetheless, it is important to point out that the Buddhist tradition, and especially the popularity of calligraphy, was increasing in influence starting from the Asuka period (飛鳥時代, 592 – 710). It was the Japanese prince Shōtoku Taishi (聖徳太子, しょうとくたいし, 574-622), who, being a great admirer of Buddhist teachings, eagerly promoted Buddhist traditions in Japan (such as copying Buddhist sutras). The custom of hanging the scrolls with ink-paintings depicting Buddhist motifs or calligraphy was further encouraged by the philosophy and doctrine of Zen Buddhism (禅宗, ぜんしゅう, zenshuu), which eventually led to developing a Japanese calligraphy style called bokuseki (墨蹟, ぼくせき, lit. “traces of ink”).

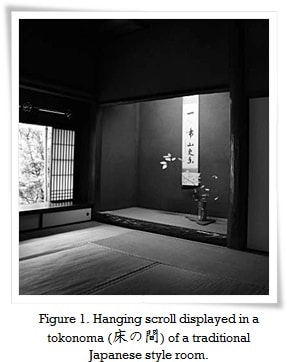

In the early 15th century the eccentric Japanese Zen monk and brilliant calligrapher, Ikkyū Sōjun (一休宗純, いっきゅうそうじゅん, 1394-1481), initiated the practice of admiring hanging scrolls with the Japanese tea ceremony (茶の湯, ちゃのゆ, chanoyu, lit. “tea (flavoured) hot water”. Note: the tea ceremony has many names in Japanese). Scrolls were displayed in a special alcove called tokonoma (床の間, lit. “a gap in the floor”), found in rooms with tatami flooring (座敷, ざしき, zashiki, lit. “spreaded seats”). Even today, traditional Japanese-style rooms are fitted with the toconoma, and a special opening in the tatami floor to place a kettle to prepare tea.

After introducing the Chinese “literati painting” school (文人画, Chinese: Wén rén huà) and its methods to Japan during the Edo period (江戸時代, 1603 – 1868), the art of scroll making flourished and various new techniques were developed. The end of the Edo period was marked by the opening of the famous school of Japanese painting called 狩野派 (かのうは, Kanōha). Its style was dominant throughout the entire Meiji era (明治時代, 1868 – 1912).

The Taishō period (大正時代, 1912 – 1926) were the last years when traditional Japanese hanging scrolls enjoyed popularity. After Wold War II, together with growing appreciation of Western fashion and life style, as well as the industrialization and rapid development of Japan, the understanding of true Japanese aesthetics has declined dramatically. Nowadays, the number of hanging scroll enthusiasts is very small, and the art of calligraphy, once again, has become a secret knowledge pursued only by a few.>

Figure 1. Hanging scroll displayed in a tokonoma (床の間) of a traditional Japanese style room. The phrase 一鳥啼山更幽 (いっちょうもなかざればやまさらにしずか, icchoumo nakazareba yama sarani shizuka), tells us a story about a secluded place deep in the mountains so peaceful and tranquil, that even a single bird cry does not break the absolute silence.

Figure 2. A fully hand-made silk scroll with cedar wood axis. Calligraphy by Kuwahara Suihō (桑原翠邦, くわはらすいほう, 1906 ‐ 1995), ink on paper. The top character means “longevity” (壽, ことぶき, kotobuki), and the bottom one means “happiness” (福, ふく, fuku).

Figure 3. Silk scroll properly rolled up and secured in a Paulownia tree box (桐箱, きりばこ, kiribako). Good quality boxes are custom made to fit the scroll they were designed for, and are assembled without any glue. Kiribako provides perfect protection against dust, stains and insects.