I still remember the first day of our posting to Thailand in the Bangkok Montien Hotel in 1987. Of all days, we arrived on Chinese New Year, and I am sure that must have influenced our family’s never-ending fascination with Southeast Asia. In the hotel lobby a calligrapher offered to write our names in Chinese characters on red paper. I still have them. All this culminated with a Chinese Lion Dance – my first contact with what later turned into a passion for all things Asian.

It was one year later that I was introduced to my first Chinese ink painting teacher, Master Lim Eow. Lessons were held once a week, and two or three students would gather around a big table in Master Lim’s modest home. He would then paint a picture in front of us from which we would practice at home and bring back our work the next week. As he and I could not communicate in English, Master Lim spoke Chinese and Thai, he would smile and spread check marks or crosses on the paper to indicate good or bad execution.

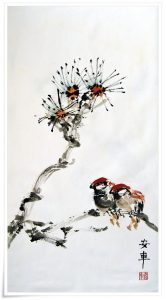

Beginning students were required to brush circles for several weeks as preparatory work for proceeding to plum blossoms, then filling pages and pages with those until at last we were allowed to paint a branch with plum blossoms. Impatient as I was, I asked about bamboo. Master Lim just smiled and had someone translate that I would need a lot more experience before being allowed to do that. Indeed, I later discovered, when allowed to paint bamboo, that to achieve what looked so gracefully swaying in a breeze was one of the most difficult strokes to master.

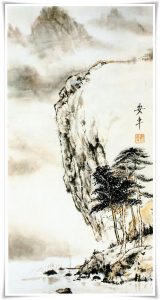

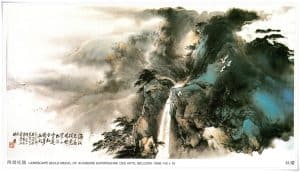

After about seven months Master Lim introduced me to landscape painting. As a geologist and nature lover I was thrilled, as that was what I really wanted to explore.

At that time Master Lim was organizing an exhibition in Bangkok with his students. It was a huge honor to be asked to be a participant. But now came the difficult part – how to sign my work with my name in Asian style. Fortunately, Master Lim had already thought about the fact that I would need a Chinese name for my work at some stage.

At first he tried to translate the meaning of my name literally, but he wasn’t really happy with the result. The words “gold” and “flames” did not make him feel at ease. From a Chinese perspective, it was not a good name. Therefore, he pondered a while over the sound of my first name and finally came up with two characters which pleased him – “an che” (安車, pinyin: ān chē), that is, “peace or stability” and “cart or vehicle”. If I understood him correctly, he interpreted the characters to mean “a safe and peaceful journey”. Of course, I liked that, that represented my life as I saw it.

Thus, with the chosen characters, I had to sign my name with brush and ink. I had, and still have, more difficulty with calligraphy than painting. I still remember the fear of setting the brush to paper for signing. A painting with which you are happy sits before you, yet it can be ruined so quickly with a poor signature. Last, of course, was the need for a seal. He insisted that the Hong Kong carvers are better than those in Bangkok. Thus, he arranged for my seal to be carved in Hong Kong.

Master (he prefers to be called Mr.) Lim Eow was born in Thailand, his Thai name is Opas Harnvanich, and he has earned quite a reputation in Thailand and internationally. Among many honors, he was invited to teach one of the Thai princesses, and in 1981 H.R.H. Maha Chakri Sirindhorn presided over the opening ceremony of Mr. Lim Eow’s painting exhibition, a great honor, of course. At the time that I was his student, he was 71 years old.

In 1988 he was awarded the Gold Medal for his work by the Academie Europeenne des Arts in Belgium.

I think he was very proud of this award. The letter he had received was written in French, so he asked me to translate it for his daughter who spoke English. I can still see his smile….

In an interview in Asia Magazine, April 1989, he responded: “ I look to many other painters for my inspiration – young ones, old ones and those in between. I can learn from them all. In fact, one of the problems I have now because of my age and my status is that nobody bothers to tell me what I’m doing wrong. Even now I’m always hoping that I can find a teacher to help me continue to develop as an artist.” Asked about his happiest moments as a painter he had pondered for some minutes and said it is his students who have given him his greatest pleasure. “I enjoy passing on my knowledge”. That certainly rings true to me, and it makes me feel very fortunate that I was able to be one of his students.

His own first teacher, in 1930, when he was 13, was Professor Liu Chang-Chao at the Paei Eng School in Bangkok and must have impressed him very much. “I can still remember his instructions”, he said. In 1934, he studied for 5 years in China with Professor Sun Pei-Gu.

He also was a student of Master Chao Shao-An, a famous Chinese Brush Painter of the Lingnan School He has several paintings in the San Francisco Asian Art Museum.

When I left Bangkok, Master Lim gave me a roll of paper for ink painting and said it would last a long time and that he hoped that one day I would teach brush painting art. At the time, I could not believe that to be a possibility ever. I interpreted that he was simply being polite, but perhaps he believed in me more than I did in myself.

I never saw myself as an artist, I just used creativity to stay sane as I could not work professionally while living in the many countries we were posted to. Now, many years later, I know that progression and paths count and that the time has to be right, you have to be ready and not rushed.

By the time we left Bangkok, I did speak Thai but not enough to understand all of the technical terms, and therefore, I only partially understood the verbal explanations. This, however, forced me to observe closely the hand of the master and, once back at home, I would play and develop my own style. This is, in fact, the traditional Chinese way of learning this art. You copy the masterpieces, you study the brush strokes – a totally different approach to the Western way of learning.

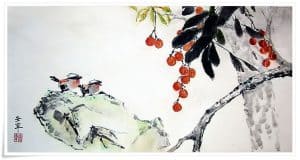

I like painting lotus, birds and landscape – mountain and water as the Chinese would call it. Chinese landscape painting is not an account of a realistic landscape, just an ideal world you would like to delve into. It exists in your fantasy only, a place where you would like to be, where you find happiness and can revere the wonders of nature. You paint not what you see but what you want to see.

In Chinese brush painting, strokes need to be executed quickly and with determination, without hesitation, and there is no room for error as Mariusz Szmerdt said so rightly in one of his articles. Therefore, practice is the core of success in brush painting and calligraphy.

I was privileged to be Master Lim’s student for about nine months, which is, of course, not long enough, but our nomadic life would lead us to Australia next.

Continue to Part II

Text, art and pictures: Antje Goldflam

English editing: Rona Conti

Copyright (c) 2012 Beyond Calligraphy & Antje Goldflam. All rights reserved.