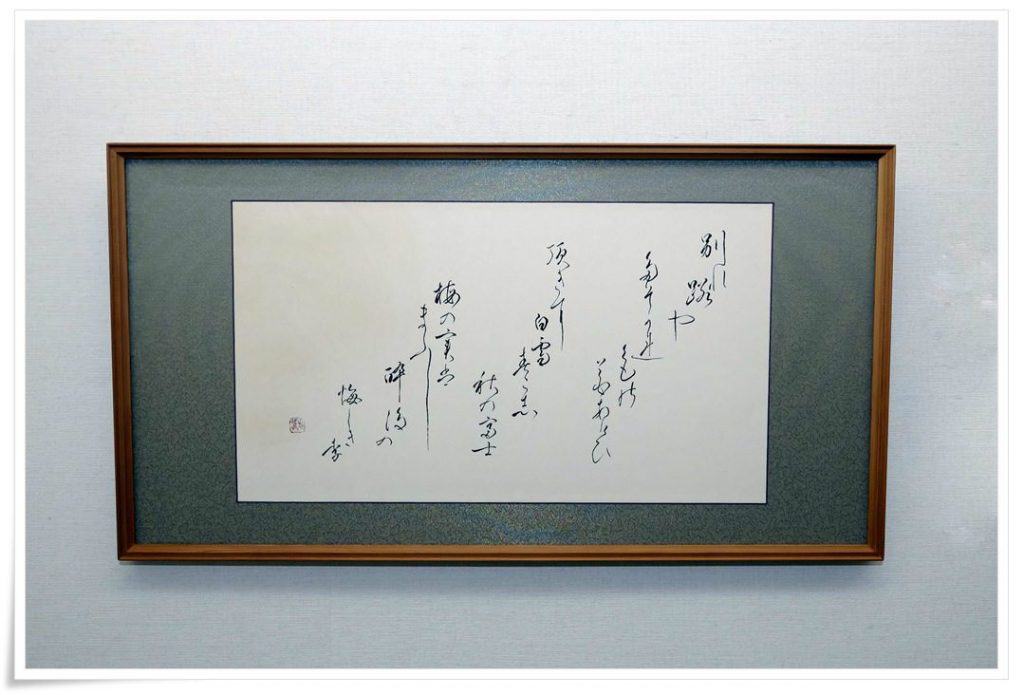

In Figure 4 you can see a small, framed calligraphy of three haiku (俳句,はいく, i.e. “a very short Japanese poem”). Haiku is governed by three major rules:

1. A verbal punctuation word that separates two ideas or verbal images.

2. It consists of 17 morae and phrases within haiku have (usually) 5, 7, and 5 morae respectively.

3. The text has a seasonal reference (which does not necessarily mean that haiku must be nature related).

As you can see, the work in Figure 4 has three haiku, but none of them has 3 verses (5+7+5) fitted into one row each. This is another example of merging “scattered writing” with the “broken writing” techniques (already explained in Part 1 of this article). Note the open space in the top-left and bottom-right corners of the work, which give it a spacious look and add a lightness to the form. It further emphasizes the gently cascading composition of this calligraphy, showing the skill of the calligrapher. Delicate ink accents suggest that it was written by a female artist. In fact, it is a work of a relative of Master Ono, Master Ono Saga (小野左鵞, おのさが).

In Figure 5 you can see both the work and the person behind the brush. The smiling face of Master Mitsuno Mihō (光野美峯, さんのみほう) and her stunning kana work incorporating two Japanese poems (和歌, わか, i.e. “waka”). The history of waka goes back to Heian period (平安時代, 794 – 1185), the time when the Japanese art was at its peak, highly influenced by the philosophy of Buddhism and Confucianism. In the Heian period, waka had many forms which varied mainly in their length. Throughout history its meaning was narrowed down to a “short poem”. Since traditionally waka is neither ruled by a stiff structure or concept (in contrast to haiku), nor encumbered with rhyming requirements, it is basically free style poetry. This particular calligraphy employs both a “scattered writing” and a “broken writing” technique.

Kana was not the only theme of the exhibition. In Figure 6 you see seven hanging scrolls (掛け軸, かけじく, kakejiku) with single characters and the signatures of the respective calligraphers below. The meanings of the kanji are as follows (in order from right to left): 喝 (かつ, katsu, i.e. “hoarse”), 麗 (れい, rei, i.e. “lovely”), 鼓 (つづみ, tsuzumi, i.e. “hand drum”, also “beat”, or “rouse”, though it may be a farfetched reference to the scenic island in China 鼓浪屿 (Chinese: Gǔ làng yǔ)), 福 (ふく, fuku. i.e. “happiness”), 超 (ちょう, chō, i.e. “superb”), 健 (けん, ken, i.e. “healthy”). Those works not only show the personal brushworks of several calligraphers, but also a variety of arrangements of the white space on the paper, as well as different preferences in materials chosen for framing.

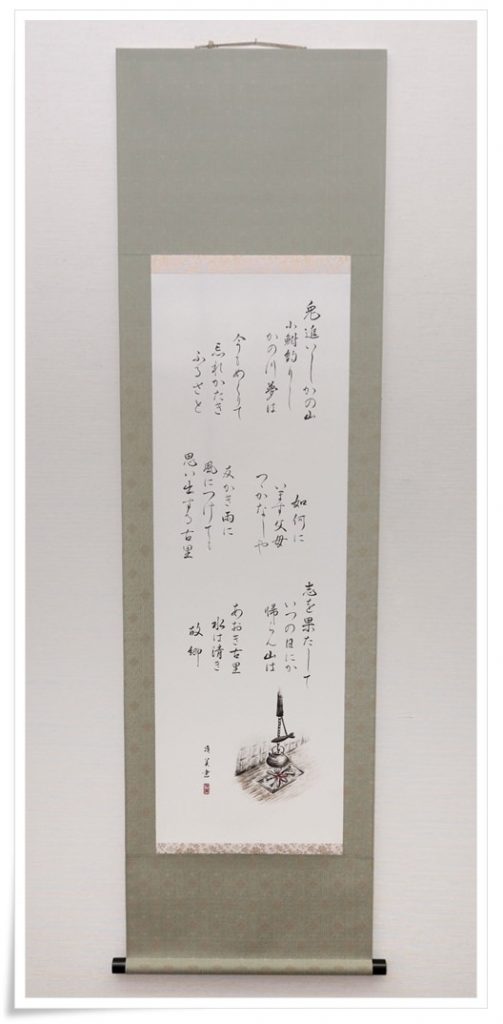

In figure 7, you can see a calligraphy of a dōyō (童謡, どうよう, i.e. “nursery rhyme”), with a small ink painting at the bottom. Ink painting and calligraphy are considered sister arts. In the ancient history of China, those who were skilled at calligraphy, ink painting and poetry, were treated with a great respect.

The text is written in historical Japanese language, which is not easy to translate, even for native speakers. In my interpretation below I tried to stay as close to the original as possible. I have also added readings of kanji in hiragana.

兎(うさぎ)追(お)いしかの山(やま)

That mountain where I chased a rabbit

小鮒(こぶな)釣(つ)りしかの川(かわ)

That river where I caught fish

夢(ゆめ)は今(いま)もめぐりて

As now, a commotion in my heart

忘(わす)れがたきふるさと

Unable to forget my home (place where one grew up)

如何(いか)にいます父母(ちちはは)

Wondering about my parents wellbeing

恙(つつが)無(な)しや友垣(ともがき)

Worrying about their health and my friends, too

雨(あめ)に風(かぜ)につけても

While facing difficulties of my own

思(おも)い出(い)づる故郷(ふるさと)

I remember my home<

志(こころざし)を果(は)たして

It revitalizes my memories

いつの日(ひ)にか帰(かえ)らん

And makes me want to return one day

山(やま)は青(あお)き故郷(ふるさと)

To the home of green mountains

水(みず)は清(きよ)き故郷(ふるさと)

To the home of fresh water

Now, I hope the ink painting seems clear in meaning. It symbolizes one’s home, which is dearly missed.