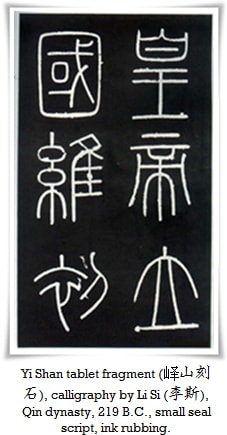

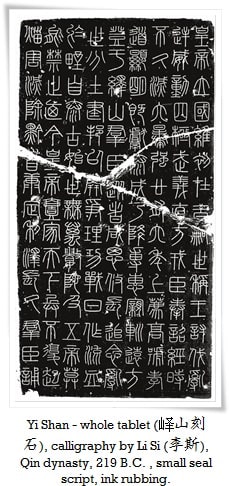

The popularity of great seal script (大篆, daiten) was further enhanced by political unrest and domestic wars between kingdoms. After the ruler of the Qin (秦) monarchy conquered the eight nations in 221 B.C., and united them under the name Qin Shi Huang (秦始皇, lit. the first Qin emperor), he introduced numerous political and legal reforms, including reforming the writing system, which were executed by Prime Minister Li Si (李斯). Over 3300 kanji were normalized in a small and vertically rectangular form of shouten (小篆, small seal script), leading further to creating the first Chinese dictionary of characters, The Erya (爾雅).

Small seal script was, however, neither an invention of one man, nor was it developed immediately. Roots of alteration that eventually led to unifying the great seal script go back long before 221 B.C., to the north-western territories of the Qin monarchy.

Aside from small seal script, there were seven other styles that coexisted during the Qin dynasty (including great seal script and clerical script – 隷書、reisho). Nonetheless, shouten was meant to be used as an official writing system. All eight styles that matured through the Han dynasty (漢朝, 221 B.C. – 206 C.E.) were known as Ba Ti (八體, “eight bodies”), although only few of them played a vital role, especially seal and clerical scripts. At the beginning, the latter was only used for everyday purposes and minor records. The eight scripts (as defined by Xu Shen (許慎, 58 C.E. – 147 C.E); a Chinese philologist of the Han dynasty) were: great seal script (大篆, daiten), small seal script (小篆, shouten), clerical script (隷書, reisho), courier voucher script (刻符, Chinese: ke fu), worm script (蟲書, Chinese: chong shu), script used for seals (摹印, Chinese: mo yin), script for ornamental tablets (署書, Chinese: shu shu) and script for inscriptions on weapons (殳書, Chinese: shu shu).

During the Eastern Han (東漢, 25–220 C.E.) clerical script (隷書, lit. “slave script”, as it was originally secondary to seal script, and mainly used by petty clerks) became the official style.

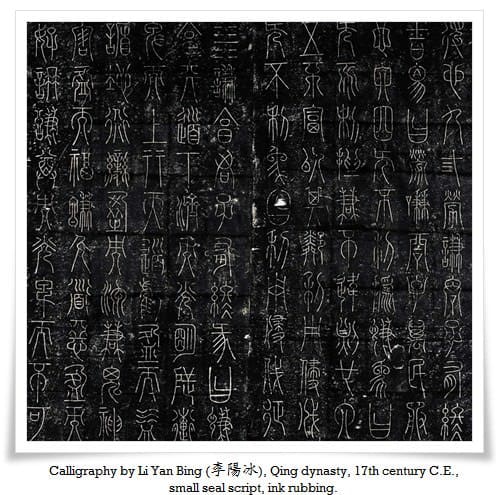

Seal script remained popular through the Han dynasty, preserved on numerous stone stelae (inscribed stone slabs), used for official documents and ceremonial purposes, inscriptions on bronze vessels, and seal carving (篆刻, tenkoku).

It is also being practiced in the modern era, not only in calligraphy (calligrapher seals, so called hanko, 判子) but also in business. All corporate and governmental offices use seals carved in seal script.

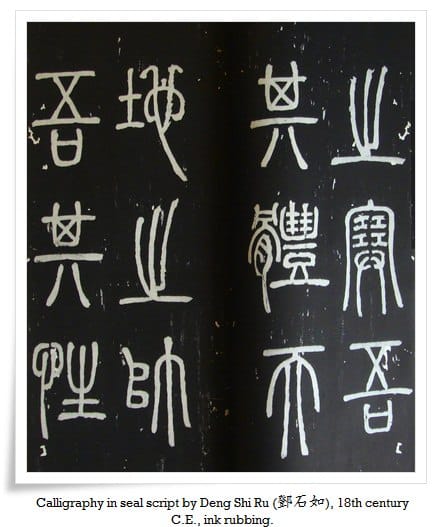

Seal script is extremely raw and of exceptionally archaic beauty. On the other hand, it is difficult to study due to its irregularity of forms and lines, as well as its complexity and, to an extent, its vague etymology. To be able to write seal script smoothly and without hesitation, one needs to study all other styles in depth.

It may appear easy to write, but in fact it isn’t. It requires a lot of skill and practice as well as superb brush control, applying the technique known in Japanese as enpitsu (円筆, lit. “rounded brush”) dependent on delivering a smooth and round line, achieved by “hiding” the sharp spear of the brush tip inside the line of a stroke, making it look rounded and smooth (藏鋒, zouhou – “hidden spear”).

Uniform stroke thickness and rounded edges are the basic rules of small seal and reisho (to a lesser extent) calligraphy scripts. The strokes should be consistent and preferably free of kasure (without white streaks within the line, caused by fast brush movement or deliberately excessive ink thickness). By rounding the line edges, the calligrapher loops the energy flow in a closed circuit and allows the spirit of his mind to live in the work forever.

Energy distribution, or energy flow, is one of the most important features of calligraphy. In Japanese it is called gyouki (行気, lit. “moving spirit”). It is defined by vigour, power, flexibility, knowledge, certainty and emotions. If one of these elements is missing, the characters look dead, pale, frozen and passionless.

The above, however, does not present the real challenge in writing a seal script, yet. The most difficult part is to make such a well-organized, neat and somewhat static character look original and alive, while preserving its “antiqueness” at the same time. It takes years and years to achieve mastery, and it comes naturally not only with practicing calligraphy, but also through training one’s mental strength. Visually harmonious and imaginative tensho does not represent the power and stability of your arm, but of our soul and mind. By “hiding the hair tip of the brush” we dismiss our pride and ego, and preserve within the lines inner harmony, that guides the soul.