Great Seal script (大篆, daiten) in the broad sense of its definition includes oracle bone script (甲骨文, koukotsubun) and kinbun (金文, literally, “text on metal”, and more precisely bronze). Great seal script was further unified in 221 B.C. under the name of small seal script (小篆, shouten).

Kinbun existed simultaneously with oracle bone script. In fact many styles were in simultaneous use, sometimes for hundreds of years or more. We still use seal script today for carving calligrapher seals, although, not only for that purpose. Corporations in kanji using countries have official stamps made in seal script, too.

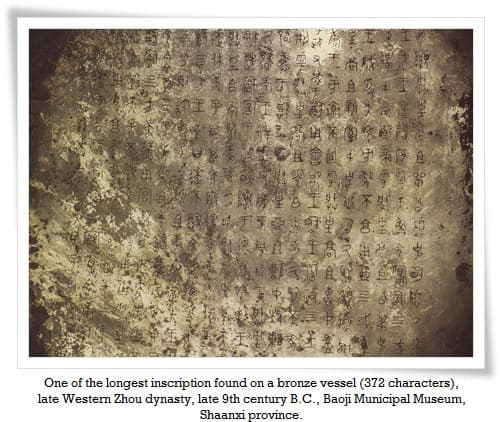

The origins of kinbun may extend back as far as the beginning of the Bronze Age in China, or the Xia dynasty (夏朝, 2070 – 1600 B.C.). At that time, oracle bone script was used for more practical purposes such as divination and recording historical events, where kinbun was playing more of a decorative role, being carved or cast on bronze tripods, cauldrons, bells and other vessels.

The interesting thing is that even though oracle bone script was the first systematic writing script in China, it is important to point out that recent findings prove that pictographic words directly related to later forms of kinbun appeared as early as the 16th century B.C, thus preceding koukotsubun.

Kinbun of the early Shang dynasty (商朝, 1600 – 1046 B.C) was used to identify the owner of the inscribed artifact, and also to express power and status of the ruler through these artifacts. One needs to keep in mind that bronze was the most precious metal at that time. Gradually, engraved bronze-ware was also used for religious purposes, for tributes of recognition from one clan paid to another, memorials honoring the deceased, etc. Those inscriptions delivered an astonishing amount of information about ancient history, as well as the development of calligraphic art.

Kinbun of Shang dynasty was extremely decorative in a way, yet simple and well designed. The variety of line thickness, the smooth curves, character size differences, and their virtually infinite forms make kinbun a real treat for both the eye and the soul.

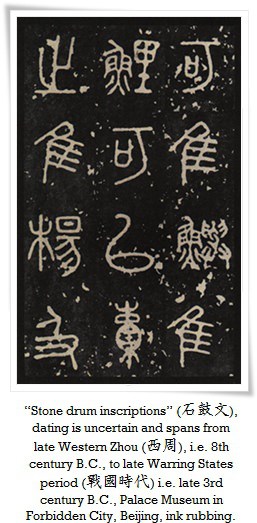

The irregularities within the script seem to dissipate towards the Zhou dynasty (周朝, 1046–256 BC). Some zoomorphic patterns were simplified and become more abstract. During Western Zhou (西周, 1046 – 771 B.C.) when ancient calligraphy reached the first peak of its development, kinbun was showing the first signs of transformation into small seal script which had more standardized character forms.

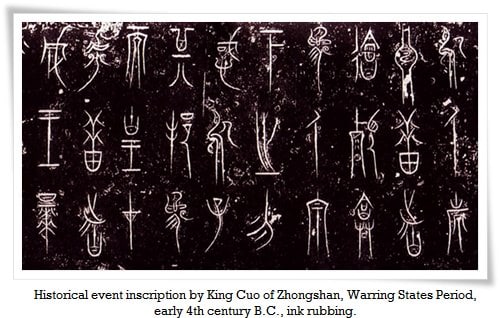

Together with the fall of the Western Zhou dynasty to a nomadic clan called the Quan Rong (犬戎, lit. “Dog Rong”), followed by three hundred years of struggle during the Eastern Zhou dynasty for supremacy over other feudal states (東周, 770 – 256 B.C.), two trends emerged. One aimed at more accurate and distinctive writing methods, cultivating the tradition of great seal script, which eventually led to standardizing it under small seal script (小篆, shouten) in 221 B.C. The other one took a more practical approach, simplifying character forms, allowing for faster and easier writing, and eventually led to the emergence of clerical script (隷書, reisho).

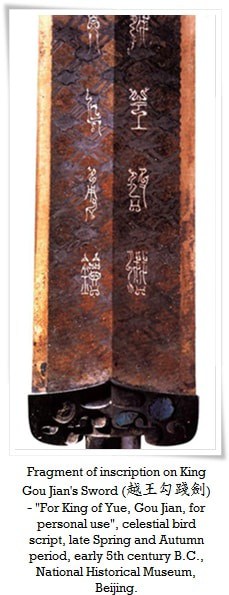

There is much more to great seal script than “just” oracle bone inscriptions and kinbun. The Spring and Autumn Period (春秋時代, 722 – 476 B.C.) was also a time when highly decorative, yet rather troublesome to read, scripts were created, with animal motifs (snakes, dragons, birds, worms, fish, etc) inter-woven into the designs. The script is generally called chouchuuten (鳥蟲篆, lit. bird and worm seal script). Zoomorphic motifs were inspired by nature, specifically the swamps and wetlands surrounding human dwellings along the Yellow River. They were used mainly on weapons, musical instruments and bronze vessels. Such decorative markings had a sacred meaning pointing at strong beliefs in the supernatural, magic and occult practices in ancient China. Those magic and lavishly decorative scripts had many forms. One of them (a celestial bird script) can be observed on King Gou Jian’s Sword (越王勾踐劍) inscription, from the early 5th century B.C.

The main characteristic features of great seal script are the irregular shape of the characters and line thickness, differences in stroke number (characters of the same meaning may have additional strokes), and non-uniform size. Characters are usually oblong, and in some cases they seem stretched out to the extreme edge of our sense of “balance”.

Engravings done in great seal script, and especially in kinbun, are absolutely fantastic. The first time I saw it, I was bewitched by its cosmic and, in a way, alien beauty. It felt as if the characters had descended from space as a gift from an unknown civilization. They are of rich and complex yet well thought out form, are unpredictable in a way, and display the incredible artistic creativity of our ancestors.

The oldest scripts also show how close to nature people once lived, and how inspired they were by it. Most people these days are increasingly removed from nature and we are obsessed with our technological innovations. If you ever happen to have a chance to admire these works, written in one of the oldest scripts on Earth, try to open your inner eyes and forget yourself for a moment. You may just find out that time travel is possible, and that the time machine is not a mythical creation, but is a cleverly concealed concept behind the gates of our very soul.

Today, knowledge of great seal script is all but forgotten, known only to a chosen few. Not many dare to enter its mysterious realm with a brush. We can take you there.