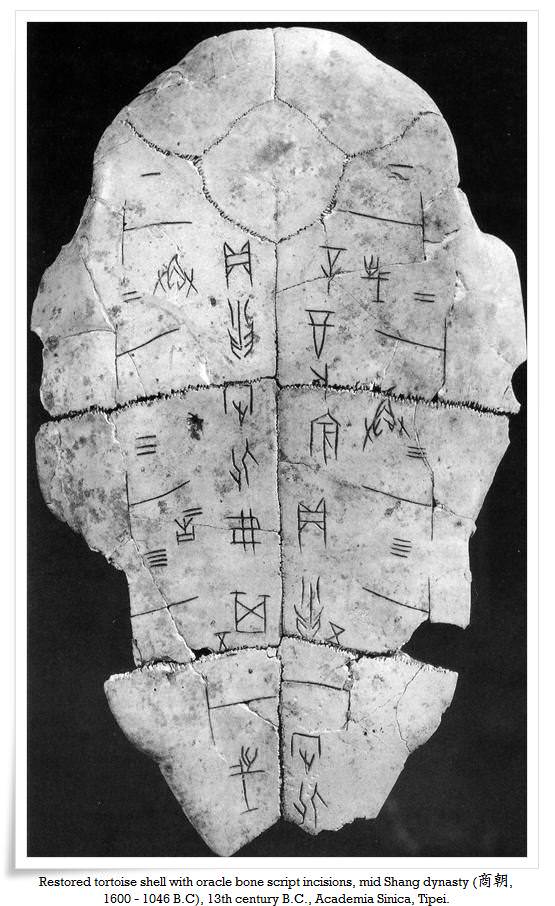

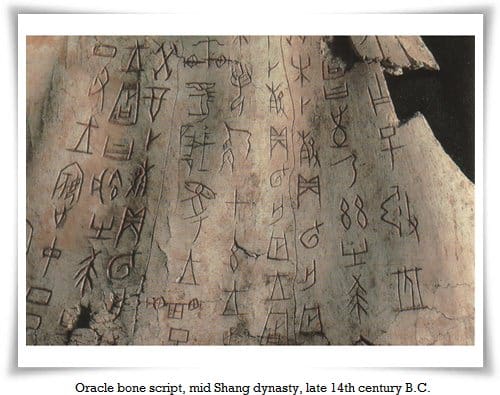

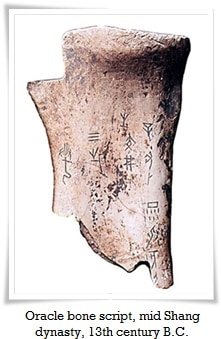

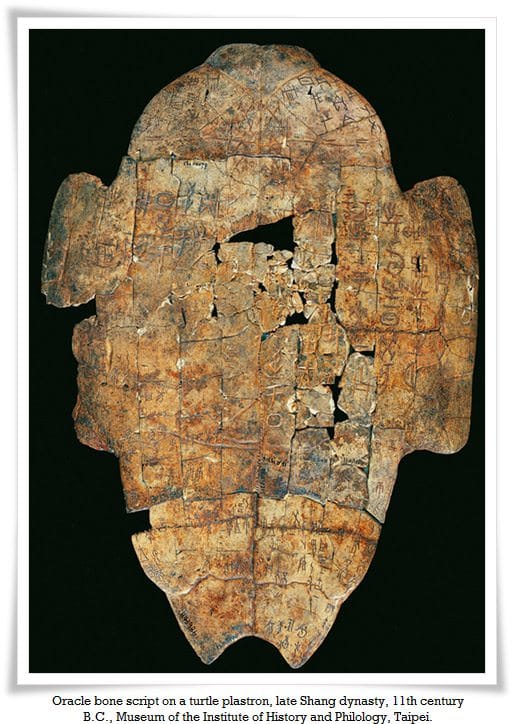

Before we dive into the vast world of core calligraphy styles in a strict sense, let me introduce you to the grandfather of all scripts: oracle bone and tortoise shell script (亀甲獣骨文字, kikkou juukotsu moji).

In short, oracle bone inscriptions are called koukotsubun (甲骨文) in Japanese, which translates to “text (文, bun) on shells (甲, kou) and bones (骨, kotsu)”. In Chinese it is also known as qi wen, i.e “engraved text” (刻, to engrave, 文, text), although there were bones found with characters written with a brush, and not carved afterwards.

Koukotsubun was discovered by accident in 1899 by Wang Yirong (王懿榮), an official from Beijing, who fell ill. A doctor prescribed him a medicine of which one of the ingredients was “dragon bone” (龍骨in Chinese: long gu). The piece of bone he had purchased from a traditional pharmacy was covered in ancient carvings resembling Chinese characters. Being a man of science it intrigued him and eventually led to a great discovery in a small village just outside Anyang (安陽), Henan Province (河南省).

Till today, approximately 150,000 pieces of bones and shells were discovered, though “only” around 2000 out of total 4700 classified characters have been deciphered. The earliest inscriptions are dated back to 15th – 16th century B.C during the Shang dynasty (商朝, 1600 – 1046 B.C.).

The main creators of texts written in oracle bone script were officials called Zhen Ren (diviner-historians), responsible for recording important events and religious ceremonies. Bones, with small dents made in them, were first heated up in fire until they cracked, which produced divinatory signs. The way the inscription was separated by the cracks suggested a divinatory sign. Afterwards, the text was often rubbed with cinnabar or ink. Thanks to those inscriptions, many interesting details regarding everyday life and records of significant political events in rapidly growing Shang society were confirmed.

Oracle bones script was not always carved. As mentioned above, sometimes characters were written by means of a brush. During the Shang (商朝, 1600 – 1046 B.C.), Zhou dynasties (周朝, 1046 B.C. – 256 B.C.), right through to the Jin dynasty (晉朝265 C.E. – 420 C.E.), bamboo and wood (many experts and historians also suggest silk) were the prevailing writing materials. Although paper was in use since 265 B.C. it was rather expensive, and until the invention of Xuan paper (宣紙) around eight centuries later, it was used only in richer circles. This extraordinarily extended period of some 2000 years has come to be known in Chinese history as the “Age of the Bamboo Slips”. Unfortunately, due to the vulnerable nature of wood and cloth, not many of these artifacts survived to today.

Oracle bone script is stunningly beautiful in its raw simplicity. It is secluded deep under a veil of primordial aura, untouchable and proud, yet elegantly brilliant. Due to the primitive tools used for inscribing the script (knives as carving tools, and low quality brushes made of rather “dull” and non-responsive hairs), the lines forming the characters resemble compositions made of wooden splinters. Strokes are canoe shaped, narrowing gradually to the sharp endings. Even curved lines are made of a series of straight cuts.

Nonetheless some of the texts on these bones show that their creators already perfectly sensed the balance of the whole composition or strokes within given character. Some of the bones bear well executed characters aside rather clumsy ones, suggesting examples written by a master for students to follow. Picture this … the first documented Chinese calligraphy “schools” are 3500 years old.

It is important to point out, that oracle bone script was not a linguistically advanced writing system. Numerous inconsistencies and irregularities of forms and meanings would lead to the conclusion that koukotsubun cannot be classified as a fully matured language transmitter.

In a broad sense, oracle bone script is included into the seal script (篆書, tensho) family, and more precisely, great seal script (大篆, daiten) – the first mature script of Chinese calligraphy. Bone inscriptions were in official use for some 800 years, until early period of the Western Zhou dynasty (西周, 1046 – 771 B.C.).

Mastery of oracle bone script takes years of devotion. The whole calligraphic journey starts with backwards learning. Student begins with regular script (楷書, kaisho; it is used commonly today in books, internet, etc.), then moves to clerical (隷書, reisho). This phase may take up to as much as a few years. Cursive (草書, sousho) and semi-cursive (行書, gyousho) scripts come next, as they require a solid foundation of balance and the knowledge of stroke order that rules the proper way of writing characters. If the stroke order is not followed, characters will look grotesque. With easily over 60000 kanji (other sources suggest as many as 90000!), you can imagine what a task it is to achieve mastery of this art.

After cursive scripts, student moves to seal scripts, of which oracle bone script is the last one to be learned. Differences between characters and their construction can be so significant that the forms of the same character written in all five styles may seem completely unrelated to each other.

Oracle bone script is usually introduced after at least a decade of diligent studies in Chinese or Japanese calligraphy. The paradox of it is, that even though it looks so primitive and simple, it is insanely difficult to execute by means of single strokes, on the one hand, to preserve its antiquity, and on the other, to let it be imbued with the calligrapher’s unique personality and style.