The origin of Chinese writing is debatable and scientists cannot settle down agreeing to a concrete point in time. We could however confidently state that it has all begun at the very moment when a human being decided to put his thoughts down in a form of symbolic drawing or abstract design, linked to an idea, feeling or a moving experience.

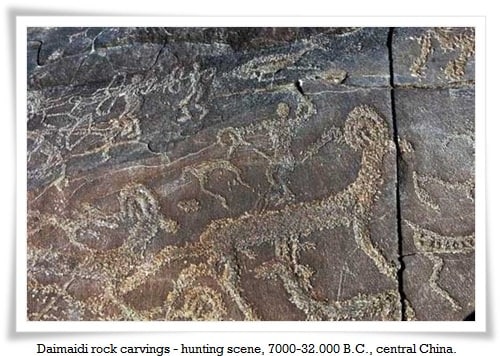

In 1988, a few thousand mysterious petroglyphs (zoomorphic characters) carved into the rocky cliffs of Beishan Mountain were discovered in Damaidi area (大麥地), Zhongwei (中衛) a prefecture-level city in China. The oldest of them were created twenty to thirty thousand years ago, whilst the latest ones were from around six to seven thousand years ago, i.e during the New Stone Age.

They mainly depict images of animals such as tigers, dogs, horses and sheep, but also scenes from life, like weddings or other ceremonies and events.

Whether those are the cradle of Chinese characters is still a mystery, though one thing is certain, that drawings from Daimadi are the oldest creations of human artistic imagination and thought, ever discovered in China.

Since Far Eastern calligraphy is based on concept of imagery and abstract visions of the surrounding world, it would perhaps not be erroneous to state that Damaidi rock carvings are the aesthetic seed of the modern art of shodo.

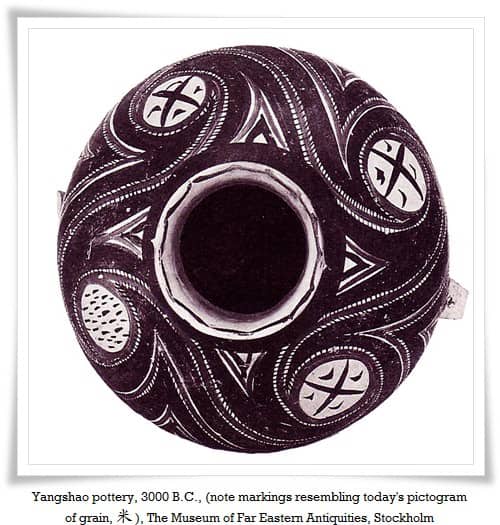

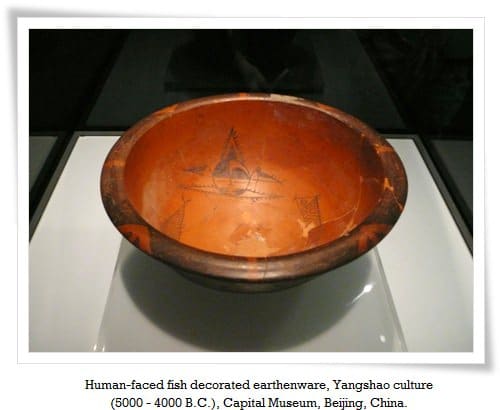

The next great step on the pages of history for the Chinese art of writing, was made in 1921 when a Swedish archeologist Johan Gunnar Anderson discovered decorated pottery near Yangshao village (仰韶), Henan Province.

Yangshao culture lasted for an astonishing 2000 years, starting around 5000 B.C. Such a span is rather unusual for the New Stone Age era. Ceramics found on the site were decorated with black, white and red markings. Some experts have successfully linked them to modern Chinese language, however the debate continues.

Even if we discard Damaidi drawings as a farfetched theory of the origin of the Chinese logographic script, Yangshao markings could be successfully classified as its beginning. Consequently, it would mean that the history of Chinese calligraphy is at least 7000 years old, 1500 years older than the most ancient written language on Earth – Sumerian cuneiform, dated at 3500 B.C.

One fact is certain, that the majority of earthenware were created on territories along the Yellow River throughout the New Stone Age, the first dynasty of China, Xia dynasty (夏朝, 2070 B.C. -1600 B.C.), and up to the beginning of Shang dynasty (商朝 1600 B.C. – 1046 B.C.).

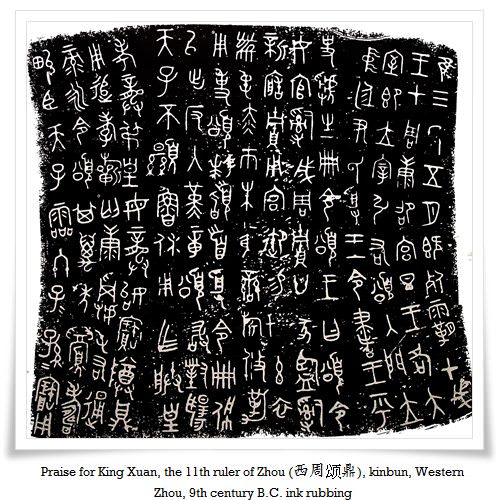

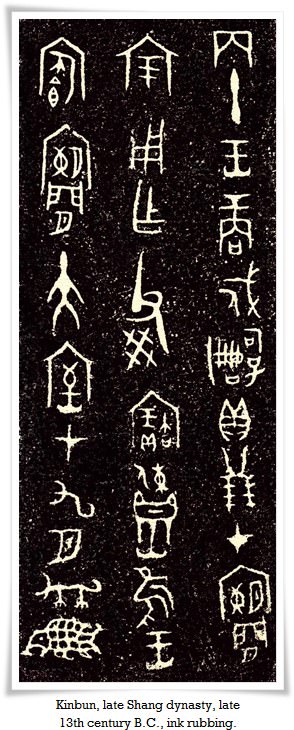

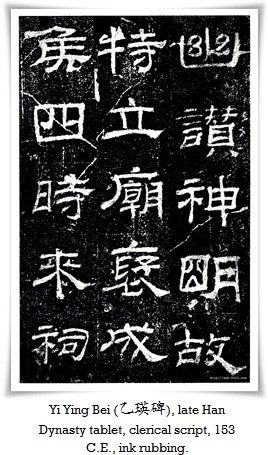

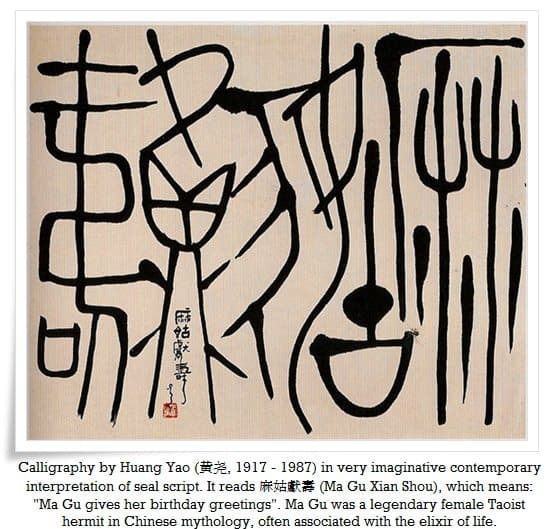

From the 16th century B.C., calligraphy evolves rapidly. Various styles come to life, starting with seal script, clerical script, then, cursive, standard and semi-cursive, respectively. Chinese calligraphy reached its full maturity in early C.E., which is when all of the styles were already in use. Nonetheless, since the Chinese writing system was introduced to other nations, for instance Japan, it kept evolving in slightly different cultural and linguistic circumstances. As a result, it led to the development of new “territorial” styles, such as Japanese kana, also known as onnade (女手, i.e. woman’s hand).

Due to the great importance and emphasis each individual country placed on the growth of the calligraphic art of the Far East, particular styles characteristic to given areas or time periods will be discussed separately. This should provide a detailed perspective and contribute to better understanding and appreciation of this remarkable art.

The question that one may ask at this point is why does such a complex writing system persist, and why it was not ever simplified (although to a degree it was, especially in The Democratic Republic of China). The answer is to be found in culture. The Western world values what is explainable scientifically or logically, thus it is touchable or definable. The East has an opposite approach to life, deeply rooted in the appreciation of nature, belief in cosmic forces, the supernatural, magic and all that is unexplainable rationally. All calligraphic theories were based on nature. Many masters were inspired by the simple sounds of a creek, falling rocks or the graceful moves of a skilled dancer. This is why the art of shodo is so elusive, making it impossible to catalogue or classify. Calligraphy is being created long before it appears on paper; in the very heart of the Universe itself.

If we look at the development of painting, the West went through a transformation from realism to abstraction of 20th century. Intriguing is what Picasso once said:

“Had I been born Chinese I would have been a calligrapher, not a painter.”

Mythical beauty and advanced imagery of calligraphy fascinated him and encouraged him to pursue a highly abstract style in his masterpieces. Now think a moment. Whilst Picasso was a pioneer of the abstract style in painting or sculpture, in the Far East it was a standard for millennia. Still today the Chinese believe that painting and calligraphy are sister arts, and the border between them is fluent. They not only complement each other but are even governed by the same rules: abstract concept, no retouching, use of brush ink and paper, etc.

In China and Japan realistic paintings were literally a taboo, and even considered vulgar, as creations bleached of any sophistication. It is believed that if one seeks in art (especially painting or calligraphy) a reflection of the real world, he has the insight of a child.

In modern times nations inhabiting the Earth are becoming one, exchange of information is instant, and cultures blend. Only recently do we see western art depicting the world as it has being accepted by Oriental aesthetics, with an appreciation for the abstract nature of reality, though still with some reserve.

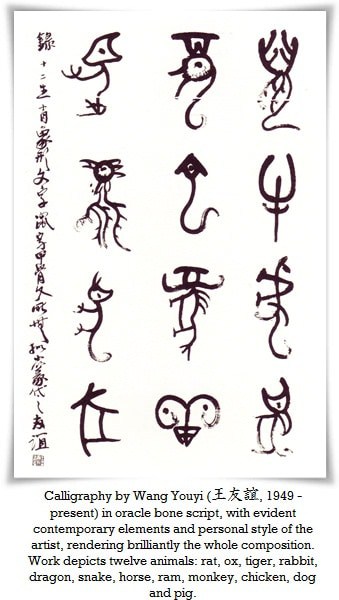

Famous words of brilliant landscape painter Shi Tao (石涛1642-1710) of the Qing dynasty (清朝, 1644 – 1912) laid the foundation for modern Chinese calligraphy aesthetics. He said that “the ink should follow the times”. Still, it was not until the 20th century that Chinese calligraphy started to deviate rather drastically from the classical rigid approach.

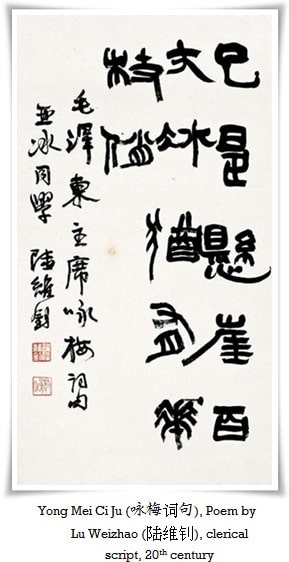

The first person who absolutely revolutionised Chinese calligraphy was Lu Weizhao (陆维钊1899-1980) who was deeply influenced by Picasso, and vice versa. He introduced a new approach to writing lines and the way that characters are proportioned, which led to new ways of expressing artist’s feelings and strong emotions. By intentional exaggeration of strokes, stretching character form, or redesigning white space around characters new intriguing aesthetics have been achieved.

Another well-known technique is using different shades of ink, just as it is done in ink painting. This was initiated in Japan but widely pursued by many neo-classicists in China. The calligraphy brush conceals countless possible ways of writing a line. For instance, repeatedly loaded with water and ink, it will deliver fascinating effects of multi-shaded lines, creating various depths and moods within one stroke. Together with the characteristic blur effect of Xuan paper (宣紙), the result is most intriguing aesthetically.

Some bold calligraphers went even further by merging two or more characters within one cluster. It may be interpreted as assimilating treasures of various cultures and unleashing them within one work. Looking at some modern abstract paintings it becomes obvious that they resemble Chinese calligraphy. So many artists of the West like Klee, Matisse, Picasso and others were fascinated by the art of calligraphy.

The essence of calligraphy, both classical and modern, stems from raw magic of simplicity and deeply natural spirituality. It should never be trivial or predictable. Even the most technically correct calligraphy can be the dullest thing on Earth. A great master calligrapher and seal carver Sha Menghai (沙孟海, 1900—1992) once said in reference to boring calligraphy:

“There’s no music in it; it’s nothing but blah, blah, blah, all the way through.”

Inspirational calligraphy ought to move the viewer to the core even if it is the most abstract work. It has music-like rhythm, a fascinating imaginative story, spectacular aura and unmatchable ambience. Anything else is not calligraphy but a waste of perfectly good ink and paper.

Obvious art is unappealing and it does not stimulate our senses. On the other hand some of the avant-garde masterpieces can leap far ahead of their times, as has often happened in the past, and be left unappreciated for centuries. Calligraphy works can be so extreme that characters become unreadable yet their meaning is still sensible through their amazing condensation of energy. This trend was initiated by the Japanese grand master calligrapher Hidai Ternai (比田井天来1872 – 1939). He was the precursor of a style known as “image of ink” (墨象, bokushou) that inspired many modern artists and calligraphers worldwide.

Even though characters in avant-garde calligraphy (前衛書道, zenei shodou) may seem to be or may actually be unreadable, it does not necessarily make such calligraphy a painting. We need to remember that although the border between those two arts is subtle, even most abstract sho is born like a phoenix from the ashes of years and years of classical studies. In any other case it would be an incomprehensible maze of lines and dots. In other words, one may not be able to “read” what is written, but can definitely feel it.

The main difference in artistic approach and philosophy is that classical calligraphy was meant to soothe the mind and harmonize energy flow, whereas its modern counterpart is there to stimulate as a visual and spiritual enhancement.

Unfortunately, in modern society there is no time, or perhaps people do not want to make time, for hours of studying classics and copying them in order to develop one’s skill. We don’t even have time to talk to each other face to face anymore, always escaping to use mobile phones instead. The ability to express one’s emotions not only via art but even words is therefore declining rapidly. The present plastic mentality is not sophisticated enough to meet the steep requirements of Chinese classical calligraphy. Sadly, fast, shallow lives, where immediate gratification is desired and viciously pursued, seem to be the predominant way of being.

The realm of calligraphy is vast, and requires venturing deep beyond if one wishes to discover its secrets, despite whether he writes or admires it. Just standing there in front of a work will not do the trick. Sho is like a living entity. It can see weaknesses, sense mindlessness and detect any reservation. One needs to deserve to be graced by the enchanted images and unrestrained passion that lurk quietly inside a calligraphy masterpiece.

Today, the majority of people do not understand the art of calligraphy. This also applies to people native to the region where calligraphy was developed. One reason is a commercial lifestyle, and another is a lack of reliable information on the subject. It is important to know that a calligrapher’s main concerns are the vigour of the patterns that characters form on the paper, and the white space secluding the black lines. Some are content with uniform and rather organised compositions, whose approach is greatly appreciated by the majority of Westerners due to its “readability”. Others seek deeper, and use their creativity for energy emanating imaginative compositions, in which symmetry and logic step aside, and life experience and the artist’s unique personality take over the work. Such works are usually misunderstood and missed for a simple reason, that people forgot how to mentally free themselves from emotional shackles of the everyday rush.