The brush (筆, fude) is the most important out of the four treasures of the study (文房四宝, bunbou shihou). It symbolizes the extension of mind and body of the calligrapher. In this capacity it is much more than just a writing tool.

The first brushes must have appeared around 5000 – 3000 B.C. together with the emergence of Yangshao culture (仰韶文化). Numerous earthenware vessels decorated with coloured markings prove the usage of primitive brushes. Naturally, they were nothing like their modern cousins and lacked many substantial features such as flexibility, ink absorbance, longevity, etc.

The first brushes used purely for calligraphic purposes appeared during the Shang dynasty (商朝, 1600 – 1046 B.C.), together with oracle bone script (甲骨文, koukotsubun). By that time historian diviners known as Zhen Ren were writing characters on animal bones and tortoise shells which were usually carved with a sharp knife afterwards, and finally rubbed with a cinnabar or black pigment. The inscriptions served religious purposes and recorded important state events.

The oldest intact brush ever found is over 2000 years old. It was discovered in Changsha (長沙), a capital city of Hunan Province (湖南). Its history goes back to the Warring States Period (戰國時代, 475 – 221 B.C.). It was made of rabbit hairs attached to a wooden handle.

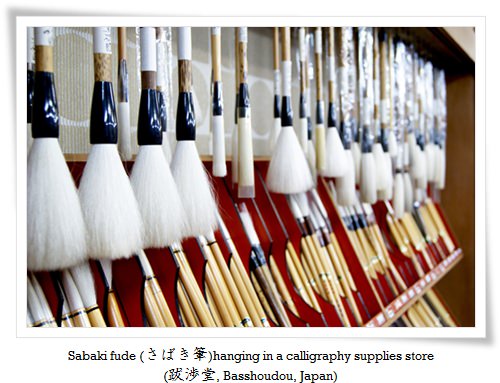

Today, brushes come in various forms, types, sizes, and quality. They are not only made of all kinds of animal hairs, but also bamboo, bird feathers, or even human hairs as well. There are also brushes manufactured out of nylon, but usually of enormous size and for writing gigantic works (such brushes can soak up to over one litre of ink!). The biggest brush made of natural hairs was manufactured in Tianjin in 1979. It is nearly 1.6m long including 20cm long hair tip (end of the tuft). The whole brush weighs 5kg.

Choosing one’s brush is like choosing one’s musical instrument. It needs to please the artist, agree with his personality, style of writing and have the desired effect. In this capacity, the specific purpose decides the brush choice.Professional calligraphers can own as many as hundreds of brushes. On the other hand, the Japanese saying: “Kukai (空海, 774 – 835)did not choose his brush” means that a good calligrapher can adapt to any writing instrument.

The brush is a living object. It is made of natural materials such as hair, bamboo, etc. If taken care of properly it will last for years, though it is not a permanent tool. Brush makers put two or three hairs inside of the tuft (the longest hairs in entire brush) and call them the “hairs of life” (命毛, inochige). They are the beating heart of the brush and if worn out the brush loses its vitality, and dies.

According to an old Japanese tradition brushes that have “passed away” are to be buried at a Buddhist or Shinto shrine. For us calligraphers who are spiritually involved in the art of calligraphy, a brush is an extension of our soul and therefore ourselves. Treating it with respect, we not only preserve the sacred nature of sho, but also allow countless hours spent on writing with a beloved brush to become an immortal memory cherished forever.