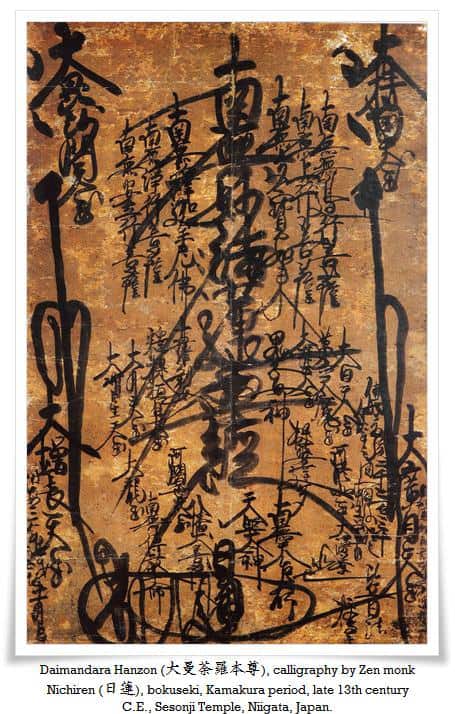

Bokuseki (墨蹟, “traces of ink”) is a calligraphy or abstract “ink painting” created by Zen Buddhist monks entranced in a meditative state. The history of Zen calligraphy goes back to the Tang (唐朝, 618 – 907 C.E.) and Song (宋朝, 960 – 1279 C.E.) dynasties of China.

Since Ikkyuu Soujun (一休宗純 1394-1481), an eccentric Zen monk who was also a refined calligrapher, initiated the practice of combining tea ceremony with admiring a calligraphy that is traditionally hung in toconoma (床の間, lit. “a gap in the floor”; a built-in space designed for displaying hanging scrolls, or ikebana), the popularity of bokuseki in Japan started to grow rapidly. Over time, meditating while appreciating a Zen phrase written on a kakemono (掛け物, lit. “hanging thing”, it is a reference to a hanging scroll) and drinking Japanese tea, has become the essence of sado (茶道, lit. “the way of tea”, i.e. tea ceremony).

In Japan, there were two main trends in calligraphy. One of them was based on Chinese tradition, deeply influenced by works of Chinese grand masters such as Wang Xizhi, (王羲之, 303–361), or those from later periods (mainly Tang dynasty). It is known in Japanese calligraphy as karayou (唐様, lit. “Chinese style”, or “Tang style”). Another trend is called wayou (和様, lit. “Japanese style”) and it is rooted deeply in Japanese aesthetics. Bokuseki was derived from karayou calligraphy trend.

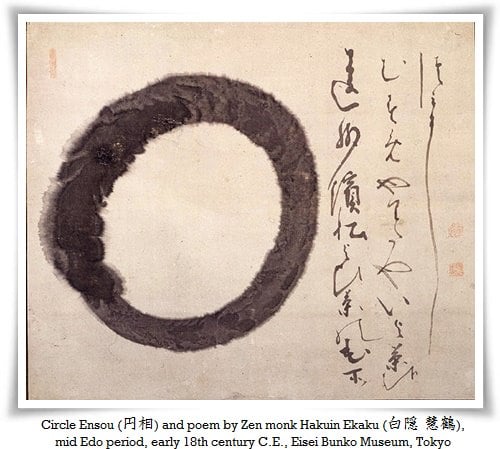

The concept of Zen calligraphy reaches deep beyond art, evoking intimate spiritual experiences. The calligrapher enters a state of mushin (無心, lit. “void heart”) which can be defined as “being free from obstructive thoughts”. Written by a mind swept of all distortions, the calligraphy becomes the void itself (空; kuu, i.e. “the void” is the highest element in the Japanese theory of the five elements, a reference to absolute detachment).

The energy emanating from such a work is overwhelming, if one allows it to reach their soul. As with traditional calligraphy, one does not read what is written, but inhales it with his senses. Bokuseki is a form without form, a direction without direction and action through inaction. It cannot be simply understood, bottled or defined. It ought to be experienced.

The main difference between traditional Chinese calligraphy and Zen calligraphy is the writing rules they obey and their total spiritual detachment. Many Zen monks, although there are exceptions, are not professional calligraphers. Their creations are meant to be ethereal and indefinable, just like prayers in Western world. For this reason they often tend not to follow strict rules of calligraphy, giving priority to expressing themselves freely and without any restraint.

Traditional Chinese calligraphy, like certain styles of wayoushodou (perhaps with the exception of avant-garde calligraphy, also known as zen-ei shodou (前衛書道), is strictly guarded by rules of writing, which were laid out by ancient masters throughout millennia either by means of calligraphy masterpieces or in the form of theories of calligraphy.If one devotes his lifetime to diligent studies, his knowledge of sho will become his nature, and his nature will become sho itself. At that point any calligraphy written by such grand master of this art will be as powerful as a mighty dragon in flight, as spiritual as most secret thoughts of the Universe, as graceful as a magnificent galloping war horse, indefinable as love, and as unique as the miracle of life.