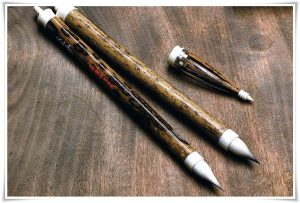

Continuing the story of the Hankeido (桂堂攀, はんけいどう, Hankeidō) workshop, the construction of maki fude (巻筆, まきふで) is most unusual. The first 3rd of the root of the tuft is wrapped and strengthened with a hand-made Japanese hemp paper, also known as washi (和紙, わし). Thus, the name maki (to wrap) fude (brush). Because of this, the hairs of the brush tip (the “spear”) have unusual flexibility and are extremely responsive. The brush’s loins are very stiff, and the relatively short hairs of the brush tip retract immediately during writing. For this reason maki fude is perfect for sutra copying where the line is very detailed and requires a very responsive brush tip. A maki fude is also most suitable for copying calligraphy classics which require precision.

What is most intriguing about maki fude is the fact that due to the stiff and unbendable base of the tuft, one cannot utilize its whole length for writing. It is important to remember this when purchasing maki fude and to make sure that this characteristic feature of its anatomy fits one’s personal writing style. Although, in calligraphy, one should normally utilise only one 3rd of the brush tip, sometimes, for artistic purposes, such as placing a powerful accent, forcing excessive dryness of line, etc., one may apply the brush with force to the paper with the intention of using the entire tuft all the way to the base of the shaft. This is simply impossible to perform with a maki fude.

Maki fude are further distinguished because the manufacturing process is rather complex and time consuming, thus, it is impossible to mass–produce them. Even though the majority of traditional high-end brushes used for calligraphy are hand-made, it is not unusual to see machine made or partly machine made brushes in calligraphy supply stores. However, all maki fude manufactured in the traditional fashion are hand-made. In modern times, this has caused a rapid decline of maki fude production.

The above describes the essential characteristic features of maki fude.

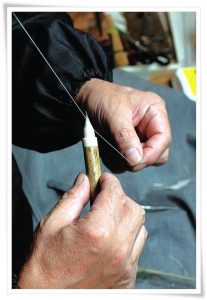

Let us focus now on the manufacturing process of maki fude. If you look at Figures 3 to 10 you can observe all of the most important steps.

First, carefully arranged animal hair is bound with a linen thread, wrapped three times around. This ensures that the shape of the tuft is secure (Figures 3 and 4). Next, the prepared tuft is wrapped tightly with Japanese hemp paper. Then, the hair at the end opposite to the brush tip is compressed with paper wrapping and shaped into the form of a small tube (Figures 5 and 6). Now the ready-made tuft can be mounted in the brush axis and glued. Finally, the loins of the brush are secured with linen thread until the glue has dried (Figure 7 and 8).

The brush tip is soaked in a special animal glue residue that hardens the tip, protecting it from being damaged until it is sold and begun to be used (Figure 9).

Maki fude nearly fell into disuse for many years. Then, some 30 years ago, a former professor of Daitou Bunka University (大東文化大学, だいとうぶんかだいがく, Daitō Bunka Daigaku), Professor Murakami Suitei (村上翠亭先生, むらかみ すいてい, 1928 – present), used maki fude for rinsho (臨書, りんしょ, i.e.”copying masterpieces”), the study of classic texts. As a result, the awareness of the importance of preserving this traditional Japanese craft increased in Japan, and the maki fude seemed restored to its former place of honor. However, the number of calligraphers actually using maki fude continued to be relatively low, and knowledge of the differences between a traditional calligraphy brush and maki fude was limited to a small number of calligraphers. Thus, while there were craftsmen able to manufacture maki fude, if the knowledge of how to use one remained marginal, then, naturally, maki fude would cease to exist, forgotten once again. For this reason, at the present time, Hankeidou is organizing multiple events that promote maki fude, allowing people to see how they are crafted and providing the opportunity for hands on use of the brush during the event.

|  |

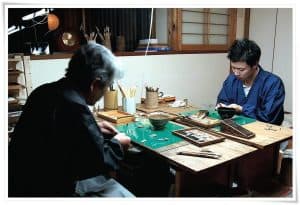

Currently, Hankeidou is the only workshop in the world that makes maki fude in the traditional way. It is owned by the 15th Generation Unpei who learned the art of brush-making from his father, the 14th Generation Unpei, starting at the age of 18. Today, he has over 40 years experience in this craft. Under his guidance, Hankeido continues to supply brushes to the Imperial Household of Japan, a tradition that goes back some 400 years. He is not alone in this endeavor, however.

Fujino Junichi (藤野純一, ふじのじゅんいち) not fully satisfied with his teaching career, decided to join his father in preserving the dying craft of Yamato. The art of making maki fude can be compared to calligraphy. It is passed on from one generation to another, and cannot survive without hands-on-experience and guidance from a skilled Master. It cannot be fully explained in written form, it has to be experienced.

Japanese text and photography: Fujino Junichi (藤野純一)

English translation and additional explanations: Ponte Ryūrui (品天龍涙)

English editing: Rona Conti

Japanese editing: Yuki Mori (森由季)

English translation and additional explanations: Ponte Ryūrui (品天龍涙)

English editing: Rona Conti

Japanese editing: Yuki Mori (森由季)