East Asian calligraphy is a very peculiar art; a life-long journey during which we learn its strict rules only to suspend them in the act of using the brush in order to write freely. Alas, without the daily practice of rinsho (臨書, りんしょ, i.e. “copying [studying] masterpieces”) all of our efforts would be in vain.

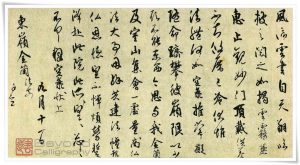

Throughout years of study I have come across many ancient classics (古典, こてん, koten) and written them repetitively. Saving one’s own work from the past is invaluable, as it allows for monitoring one’s progress (Figure 1). Further, my teacher’s advice has been to not continuously copy one particular text, but to keep moving, choosing another example of historic text or changing brushes and trying to approach the same text from a different angle whilst maintaining its key characteristic features.

During the first years of study, when one’s shofuu (書風, しょふう, shofū, i.e. “personal handwriting style”) is at its most vulnerable stage and still evolving, it is not advisable to learn from excessively long masterpieces. Just as one learns as a child through repetition, actions leave imprints on the brain, and, whether for good or ill, these may solidify as habits. Mountain climbers pre-analyse their adventure months in advance, carefully assessing each approach. Their lives depend on the quality of their research. So does your shofuu.

Each of the great calligraphers had his own style, and, even though they did influence one another greatly (see Part I of this article), their mature styles were exceptional and independent. Understanding the nuances of these masterpieces is crucial for revealing hidden secrets of the brush. Those secrets gradually unfold and become pieces in a magnificent puzzle, contributing to developing handwriting characteristics.

Before writing rinsho, I always try to obtain the printout of the entire work (both in colour [if available] and ink rubbing [拓本, たくほん, takuhon]). Naturally, sometimes it is impossible, as some works are a few thousand characters long, and they need to be split into pages. Nonetheless, it is important to look at the whole from a bird’s eye perspective and understand the concept of the entire masterpiece (again, the forest comes first). This is why many great calligraphers travelled. They did so to enrich their life experiences, as well as to see the calligraphy monuments or works of other masters in the collection of a particular person.

Furthermore, I try to study the calligrapher’s biography, the period in which he or she lived, or a specific reason (if any) that initiated writing a given work or events that may have influenced it. If I am able to find them, I even buy books devoted to individual masters and read about what kind of life they led. Understanding the emotions and history behind the work is quite important, particularly since East Asian calligraphy is a child of one’s soul, being written with one’s heart and not brush.

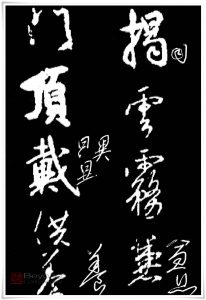

A large printout allows me to make notes, and glosses in places where the script is unreadable or blurred (Figure 3 and 6). Sometimes, I even use a magnifying glass to confirm the direction of the line (Figure 4). There is nothing worse than writing erroneous forms of characters without understanding and having consulted multiple dictionaries. I wrote “multiple” deliberately, as even the best dictionaries may have mistakes.

For instance, click here and see the article on the etymology of the character 五 (ご, go, i.e. “five), and read my commentaries in regards to Figure 4. After you have done so, and because you have the entire text of the “Letter carried by the wind” shown in this article (Figure 2), you can easily note the significant typo in the dictionary. Once again, cross referencing various sources is crucial. Additionally, I often confer with my teacher, just to make certain that my understanding is correct. A good calligraphy teacher is like a treasure map. He or she will give to you hints and suggest directions, but let you choose the path to reach the “X” mark on the map. To illustrate, here are two passages from my book titled “Marvelous Ink” (writing in progress), in which I refer to two separate quotes of my teacher:

Once I asked him (my teacher, i.e. Kajita Esshuu [梶田越舟, かじたえっしゅう, Kajita Esshū]) what criteria he follows when purchasing a hanging scroll or a framed work of another calligrapher. He put his brush on the fudeoki (筆おき, ふでおき, i.e. “brush rest”), looked at me and smiled:

“If I buy a work it is only to hang it in the tokonoma (床の間, とこのま, i.e. “an alcove in a Japanese style room”) for my students to observe and broaden their vision. Sho (書, しょ, i.e. “to write”; here: “East Asian calligraphy”) is an art that allows you to roam wide seas of imagination. Those seas are boundless, made of many isles and straits, and one should not be afraid of going into foggy and untraveled areas. Only you can decide what meshes with your personality, or what style of writing you should follow during your journey. I can only help you to build a boat. It is you who must learn how to sail it, to use your instincts and knowledge of calligraphy to determine in which direction to head.”

Regarding rinsho, he said the following:

“Whilst studying rinsho and learning from the greatest masters, remember that solid steps will be built to the shrine of understanding the true essence of calligraphy”.

For the purpose of clarifying a few things about rinsho, I will use Kuukai’s (空海, くうかい, Kūkai, 774 – 835 C.E.), one of the legendary Sanpitsu (三筆, さんぴつ, lit. “three brushes”) of the Heian period (平安時代, へいあんじだい, 794 – 1185 C.E.), “Letter carried by the wind” (風信帖, ふうしんじょう, fūshinjō; Figure 2), which is considered to be the most outstanding Japanese calligraphy masterpiece in semi-cursive (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) script. “Letter carried by the wind” is a reference to three letters addressed to the Buddhist monk Saichō (最澄, 767 – 822), the founder of the Tendai (天台宗 Tendai shū) Japanese school of Mahayana Buddhism. 風信帖 was the first one that was sent. Kuukai is asking in his letter whether or not Saichou would be interested in meeting and discussing the particulars of Buddhist philosophy and its roots (Kuukai was the founder of Shingon Buddhism doctrine [真言宗, しんごん しゅう, Shingon-shū]).

“Letter carried by the wind” clearly shows Kuukai’s appreciation of Wang Xizhi’s (王羲之, pinyin: Wáng Xīzhī, 303 – 361 C.E.) style, especially the one in the “Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion” (蘭亭集序, pinyin: Lántíngjí Xù). For this reason, it is good to look at both masterpieces side by side and study them together. Kuukai’s writing is fast, yet elegant, somewhat emotional, yet scholarly. He skillfully manipulates the brush with different forms and moods, yet still is perfectly able to maintain consistency throughout the text. The second letter to Saichou (titled 忽披帖, こつひじょう, kotsuhijō) is much more emotional and aspirational.

There are various theories about which year the “Letter carried by the wind”, and the two other letters to Saichou, were written, but most historians and specialists estimate that all were sent between the years 810 and 812 C.E. This means that the correspondence took place after Kuukai’s trip to China during which he met and befriended Saichou. It was an exchange of messages between good friends and that relationship greatly influenced the style therein. More in-depth analysis of the text will be presented in an article devoted to either Kuukai or “Letter carried by the wind”.

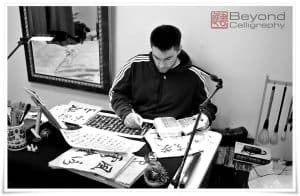

Figure 5. A short movie in which I write rinsho (臨書, りんしょ, i.e. “copying {studying} masterpieces”) of first 12 characters of the “Letter carried by the wind” (風信帖, ふうしんじょう, fūshinjō) can be found here. This is the third time that I write this classic, but definitely not the last one.

There are two major approaches or studying techniques for rinsho. One uses tracing paper, whereas the other is to copy free-hand. The tracing paper technique is invaluable for understanding the details of a given work, the characteristics of the brush strokes, etc. It is performed in this manner: a tracing paper is placed over a copy of a masterpiece, and all lines of characters are traced with a pencil. Once the template is ready, the calligrapher writes over it with a brush, as he would normally do, but pays attention to being very precise with each brush stroke and staying within the lines drawn by the pencil.

The other method is that of copying a masterpiece on a clean sheet of paper by looking at the original placed on the left-hand side, just as I do in the movie shown in Figure 5. If you notice the movements of my head, you will see how often I look at the masterpiece during the writing. Any unclear details need to be either researched or studied with greater intensity (Figure 3, 4 and 6).

In the free-hand copy rinsho method we can distinguish two approaches. One is to copy the text exactly as it is (mirroring). The other is based upon the idea of copying only the characteristic features of a given masterpiece while imbuing the characters with one’s own handwriting. The second method is decidedly more difficult and involves many years of practice. Not only does it require a mature shofuu, but also the experience of manipulating and tweaking one’s own style.

The last method would be to write from memory. That applies to all methods of rinsho studies. In Japanese it is called hairin (背臨, はいりん, i.e. “copying from a masterpiece without looking at it”). This is a very challenging technique but invaluable for improving ones writing skill. It summarizes and defines how much one has learned during practicing rinsho.