Reading handwritten letters from my Grandmother was always a difficult problem for me. Her handwriting looked like scribbling to a teenage girl, and I used to request that my Grandmother write more properly using block-printed letters. It was only when I discovered Kana-Shodo that I understood that her handwriting was not just a scribble but that she was using old traditional Hiragana, a heritage of deep Japanese beauty from the Middle Ages.

Hiragana, or ancient traditional Japanese characters which developed from the Kanji characters imported from China, reached its zenith in the 10th century among aristocratic women. Writing in Japan before Hiragana was invented meant writing using only Chinese Kanji (Hanzi) symbols because Japanese did not have their own writing system. Men in Japan had to learn Kanji symbols in order to read Buddhist sutras or diplomatic documents from China. One can compare this to Latin in Europe. Women in Japan in the Middle Ages were not expected nor encouraged to learn Chinese and Kanji since they were used in diplomacy and politics in which women did not participate. Thus, when Hiragana characters were developed from Chinese Kanji (Hanzi), women in the upper class did their best to try and show how fluently they could read and write.

In my opinion, Kanji represented the world of careers in Japan, and Hiragana was more related to leisure, hobbies, or cultural aspects of life. Writing novels, writing a love letter, exchanging poems in Hiragana helped Japan to attain its uniqueness and its own culture to bloom. The first significant literary masterpiece in Japanese history, “Genji Monogatari“, was written by a noble woman using Hiragana in the 11th century.

Unfortunately, the Hiragana symbols which are used in Japan today are only a small part of a rich Hiragana culture which has many hundreds of characters. One reason for the rich variation of Hiragana is that the noble class gave much thought and effort to creating new variations of Hiragana in order to show their sophisticated intelligence. This complexity later caused a perceived problem for literacy in Japan. Thus, in order to simplify learning for the overall population, the Meiji government decided in 1900 to reduce the number of Hiragana taught in schools. The government chose only roughly 50 symbols out of hundreds of Hiragana to be used in the educational curriculum and named them “Gojuon”, which means 50 sounds.

Additionally, the fact that traditional Hiragana characters are often written connected to each other made it even more difficult for them to survive the modernization of Japan because they were not suited to the printing system.

My grandmother is one of the last generations to use the old Hiragana in daily life. By contrast, my Father, who was born in 1936, the year when “Modern Times” was released by Charles Chaplin, did not even know that this traditional luxurious culture of Hiragana existed. As Charles Chaplin has described in his film, anything inefficient was banned in “Modern Times”. And thus, so were complex Hiragana characters, representative of a leisurely and creative pursuit, abandoned and forgotten in Japan.

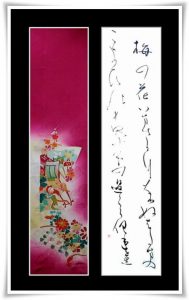

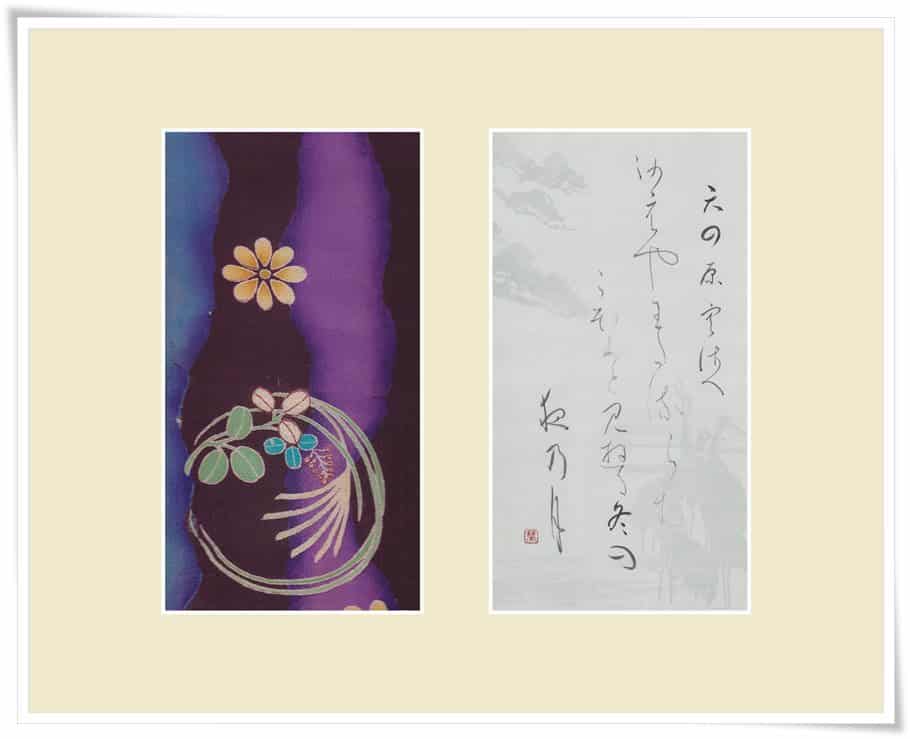

Today, like my Father, the majority of people in Japan do not even know of Hiragana’s past existence and history. Kana-Shodo is a traditional Japanese calligraphy which represents the inheritance of the aristocratic noble women’s culture in the Middle Ages. The beauty of inefficiency lives today only in the world of Kana Shodo.

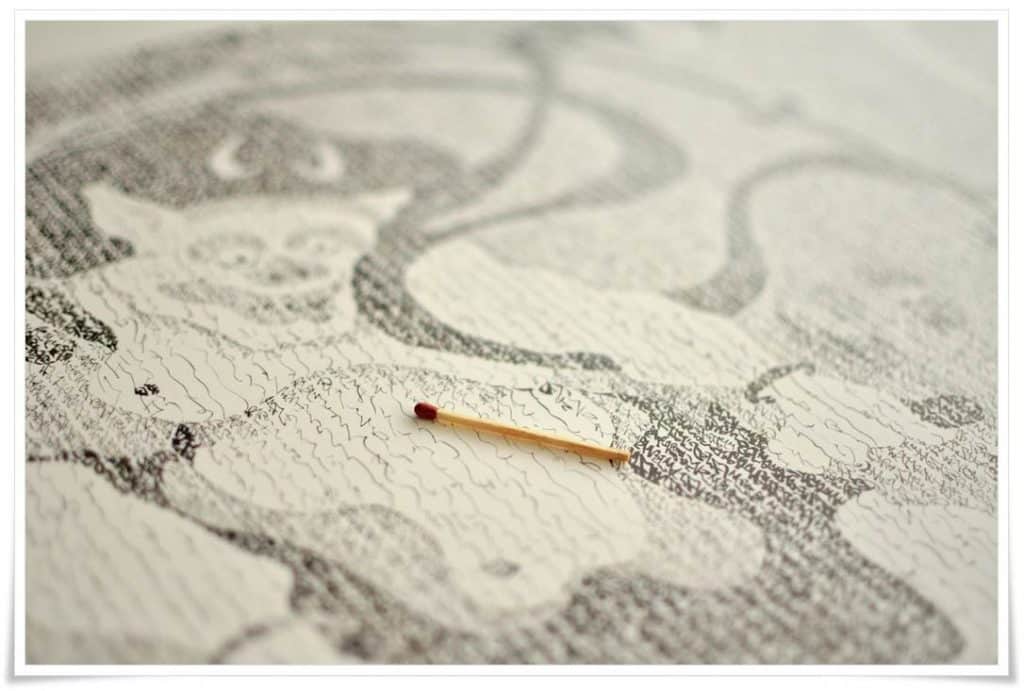

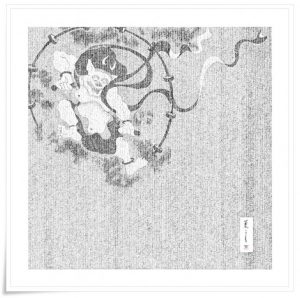

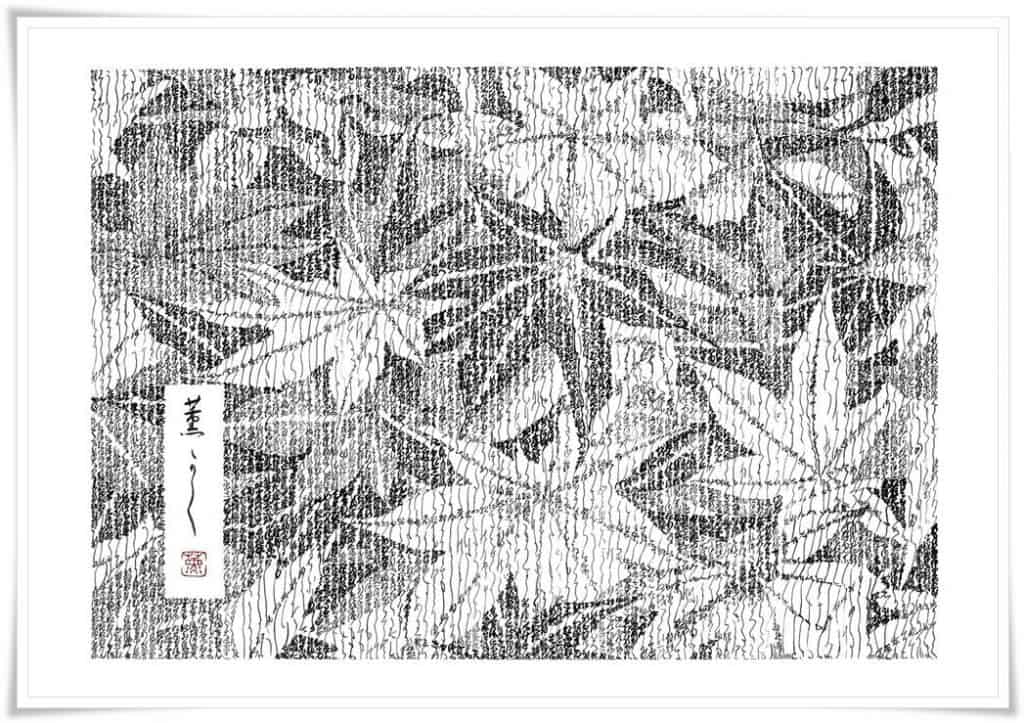

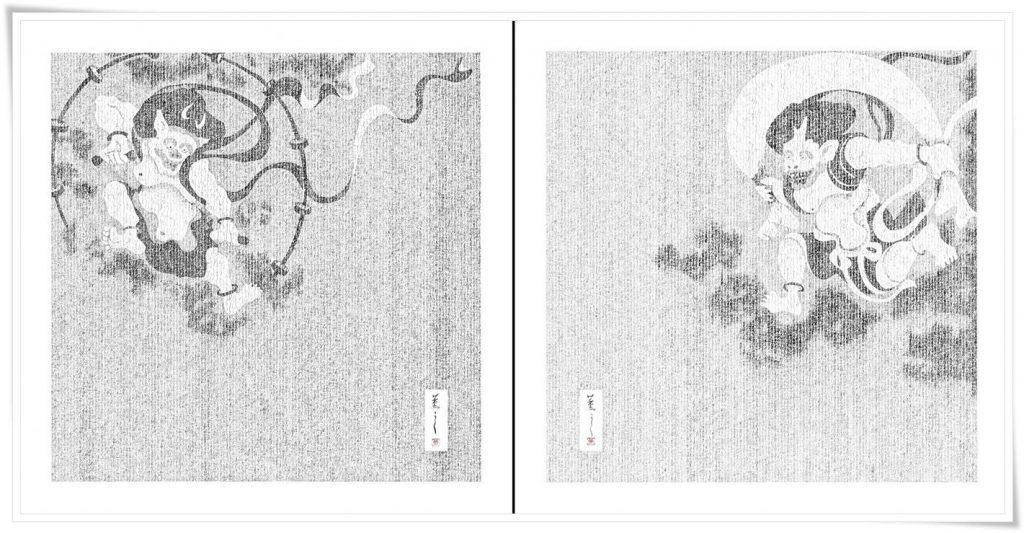

My art, Kana de l’Art, is a challenge to revive these ancient traditional Hiragana characters in modern times, using my technique as a Master of Kana-Shodo. I create images using small Hiragana characters of varying thickness and darkness. You may say that it is even more inefficient than Kana-Shodo itself, since I must pay attention not only to my handwriting but also equally to whether or not the image reflects my pre-visualization, how I imagine the work to take form. It is incredibly time consuming. I sometimes spend months to complete one work. My style may not match modern times, but I am proud to be inefficient. And I am completely confident that my art is truly “Beyond Calligraphy”.

Kaoru Akagawa March 2013

To learn more about Kaoru Akagawa and her art, please visit her website. If anyone missed Akagawa-san video which was done for The Avant/Garde Diaries it can been seen here.