日本語版はこちらからご覧になれます。

Sakiko Yanagisawa conducted an interview with Japanese Calligraphy Master Yamada Shuuya (やまだ しゅうや, 山田修也) in conjunction with the recent exhibition Yuyu. Master Yamada is the organizer of “Calligraphy Friends From All Over Japan” and a member of the judging panel of the Mainichi Shodo Exhibition, one of the largest public competitions in Japan followed by a hugely popular exhibition. Beyond Calligraphy, through Sakiko Yanagisawa, interviewed Master Yamada whose success in his calligraphy career is inspiring. We hope that you will enjoy the interview!

Sakiko Yanagisawa (S.Y.):Master Yamada, could you please tell us your overview of calligraphy (sho).

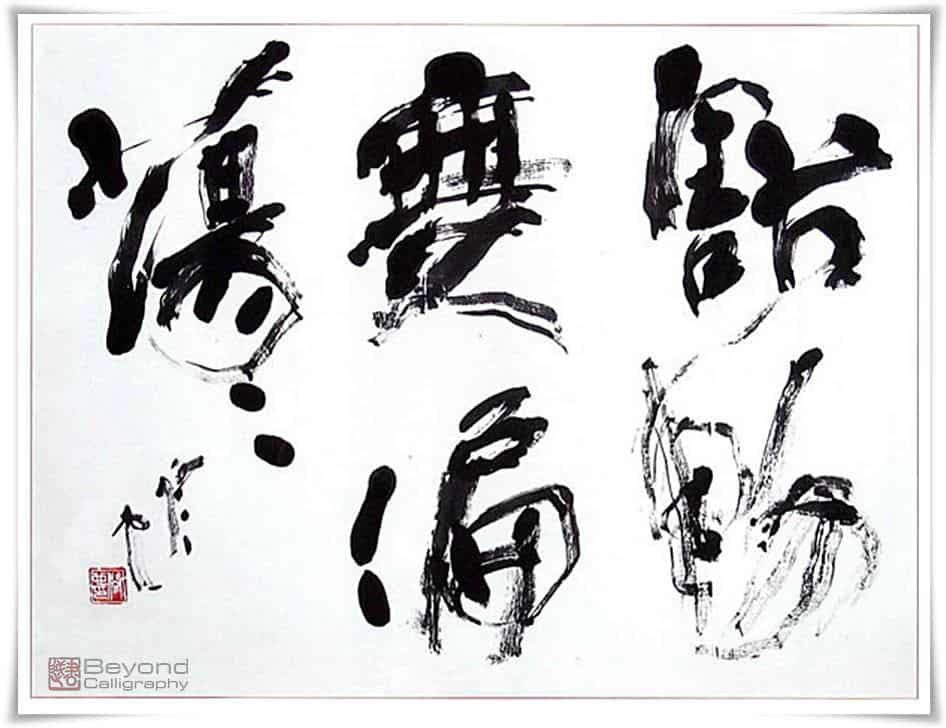

Master Yamada (M.Y.): The echo of the ink, the way in which it interacts with the paper, is most important. My work varies with and responds to how the echo of the ink becomes the characters I am writing. If you concentrate on how to write each character beautifully, your work will be as fine as possible.

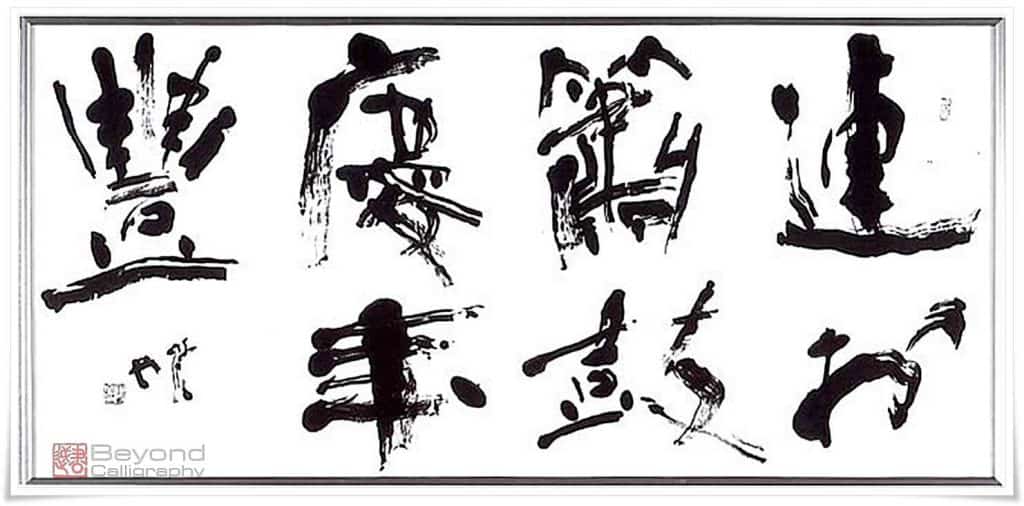

I would say that my work lies somewhere between the avant-garde and what is thought of as more traditional calligraphy. Works should be beautiful and compelling even when viewed from different angles and when looking at different parts. When I see individual parts, viewing them one by one, I would say that my work is avant-garde. When I make marks on the paper and they evolve and happen to become characters on the paper, my sense of fulfillment is enormous.

It is said that sumi (ink) is superior to the five basic colors found in other mediums, paint, colored pencils, etc. Two characters express this concept of old (五彩). Ink can be mixed in different concentrations, thereby making far more than just five colors. Therefore, calligraphy (sho) is the specific art of writing characters marked by myriad shades of ink.

S.Y: What constitutes a good line?

M.Y: A good line should be soft, yet strong, like the candy “chitose ame” used for the Japanese celebration shichigosan. What I mean in making this reference is not that the line should have the strength of iron but rather that it should be just strong enough so that it is not too soft to be broken. This is a nuance in calligraphy which one develops with the brush, but when I feel this kind of strength in a work, I believe that it is made up of good lines and is, therefore, a good work.

S.Y: Why did you begin the study of calligraphy?

M.Y: When I was in elementary school, my teacher said that I was restless and misbehaved. My parents thought that if I studied calligraphy, I might behave in school. However, my behavior in school did not change from studying calligraphy. I studied calligraphy with a teacher near where I lived from the age of eight until I went to high school.

S.Y: How did you meet Master Ishibashi Saisui (石橋犀水), and how did it change your life as a calligrapher?

M.Y: When I was a high school student, I began to exhibit my work in many places and received prizes from the Ministry of Education. That gave me confidence in my work, and from that time I began to think about life as a calligrapher.

My calligraphy teacher in high school was a disciple of Master Ishibashi Saisui (石橋犀水), and I was advised to become a disciple (student of) of his also. Thus, I entered the School of the Japan Society of Calligraphic Education (日本書道藝術専門学校) for the first school term with a letter of recommendation from my teacher. I studied calligraphy at that school for 3 years.

Later I was a calligraphy student at different universities, then became an assistant of Master Ishibashi. I then became one of the leading staff members at the School of the Japan Society of Calligraphic Education and taught calligraphy by being a lecturer and other things. At that time, there were lots of famous teachers thanks to Master Ishibashi’s human network. Several years later, I left the school and became an independent calligrapher.

S.Y: Can you please tell us more about Master Ishibashi Saisui (石橋犀水)?

M.Y: Master Saisui loved calligraphy. He became famous because of his passion for calligraphy and his perseverance. He wrote, wrote, and wrote, and pushed hard and strove for versatility. He was also a pioneer. He was not only excellent at calligraphy but also had a great ability and warmth and thus attracted many people also passionate about calligraphy.

Of the many things I learned from Master Ishibashi one was especially important. He said that I should write letters with my own hand-writing soon after someone did something kind for me. I learned that it was very important to show gratitude with my brush, not only by making a telephone call as a thank you. And, of course, I learned that I should always try my best at what I love.

S.Y: What do you enjoy the most about calligraphy?

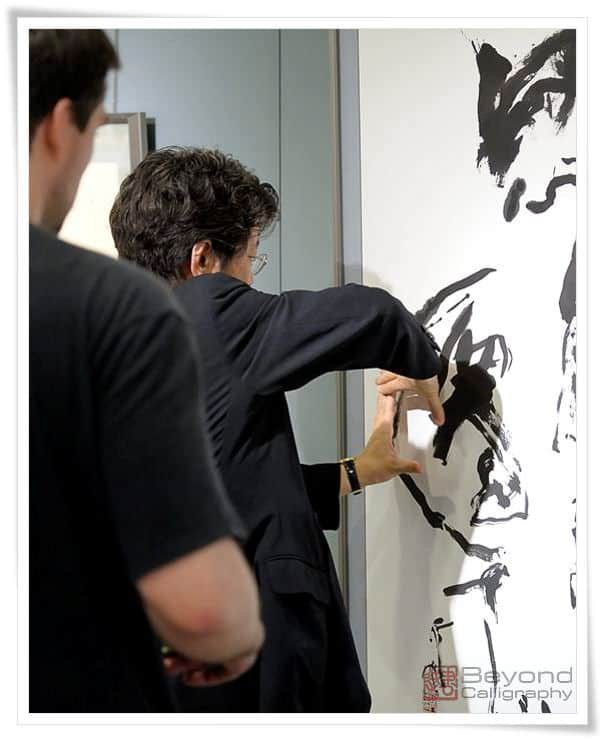

M.Y: I love the moment when I place one drop of ink on white paper. I feel the echo of the concentration of the ink and how it echos in my heart. I like spiritual Zen words, but I believe that the emotion the ink expresses is more important than the words themselves. We should not focus only on the words and characters but on the emotions evoked.

The echo of the ink can only be presented through ink. Sumi-e is also an art of ink, but it is different because sumi-e (sumi = ink, e= picture or painting) can be added later. Sho is the art of the moment, so it is the feeling which is the most important.

S.Y: Can you tell us the main reason for your studying of sho?

M.Y: In brief, my reason to study sho is to make my life fruitful and productive.

S.Y: Do you like teaching?

M.Y: Teaching is a process by which one gets to know a person and allows that person to know himself. In this way I like teaching.

S.Y: Who are the people from the past to whom you look for inspiration, your favorites?

M.Y: My three favorites would be Tessai Tomioka (富岡鉄斎), painter, Beizan Miwata (三輪田米山), Head Priest of a shrine, and Jiunsonja (慈雲尊者), a Buddhist monk.

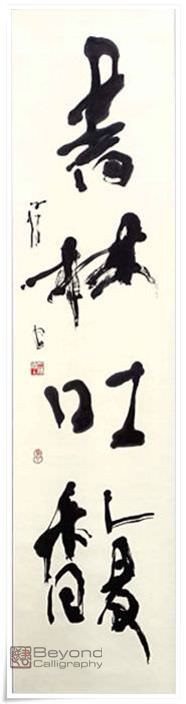

All three are not calligraphers, but at the time it was not possible to be a full time calligrapher and support oneself. Thus they supported themselves while doing calligraphy but as painter, priest and monk. In the Meiji Era it became possible to become a full time calligrapher, as illustrated by the pioneer of calligraphy Meikaku Kusakabe (日下部鳴鶴) who through his teaching and his work showed the way to bring calligraphy into the modern era.

S.Y: What is your favourite period in calligraphy (sho) history?

M.Y: It is difficult to choose, but if I have to choose one, I would choose the Nara period because that was the first time in Japanese history that the Buddhist sutra came to Japan. That time was, I believe, the beginning of sho and of the grass roots of Japanese characters.

S.Y: Which do you prefer, a big work or a small one?

M.Y: I cannot choose. I write with the same passion for both big and small works. Therefore, I like both.

S.Y: How do you express yourself through sho?

M.Y: Sho is the path of my life. I hope that my life will have been fruitful when I die. I want to be a pioneer in many ways, in my style of sho, in how I interact with people, growing the next generation of calligraphers whilst appreciating people and their work in the past. I think that that is fundamental for artists.

The word “Shodou (書道=calligraphy)” focuses on the word “Dou (道=path)” too much. “Sho (書=to write)” or “Shogei (書芸=performance of calligraphy)” sounds better as a representation of what sho is to the global world.

S.Y: How do you encourage young people to continue calligraphy?

M.Y: I try to teach them how much fun they can have doing calligraphy, how much enjoyment they can get from something which can be done with ink alone. I also suggest that people share their work with each other, look carefully at it, comment on it. To critique work and have your work critiqued gives you the chance to improve, but it is also suggested that it would be important to be humble. Being humble is also essential when you exhibit your work.