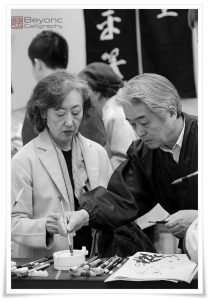

In February of 2012, Beyond Calligraphy, together with Master Calligrapher Sakiko Yanagisawa (柳澤咲子先生, さきこ やなぎさわ せんせい), visited a cultural event held in one of the Takashimaya department stores in Ginza, Tokyo. We were invited by the owners, father and son, of the Hankeidou Workshop (攀桂堂, はんけいどう, Hankeidō) of Shiga prefecture (滋賀県, しがけん). Its history dates from the Shoutoku Era (正徳年間, しょうとくねんかん, Shōtoku Nenkan, 1711 – 1716).

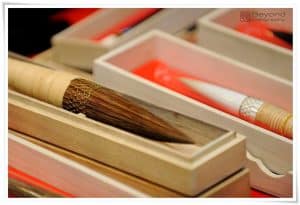

The Hankeidou workshop is renowned for manufacturing traditional Japanese brushes, known generally as unpei fude (雲平筆, うんぺいふで), a tradition started by Fujino Unpei (藤野雲平, ふじの うんぺい) some 400 years ago during the Genna Era (元和年間, げんな ねんかん Genna Nenkan, 1615 – 1624). Unpei fude is a category of several types of brushes, tenpyou hitsu (天平筆, てんぴょうひつ, tenpyō hitsu), hitsu ryuu tou maki fude (筆龍藤巻筆, ひつりゅうとうまきふで, hitsu ryū tō maki fude), koubou taishi ryuu hitsu (弘法大師流筆, こうぼうたいしりゅうひつ, kōbō taishi ryū hitsu), teika ryuu hitsu (定家流筆, ていかりゅうひつ, teika ryū hitsu), and jou dai you fude (上代様筆, じょうだいようふで, jō dai yō fude), among others.

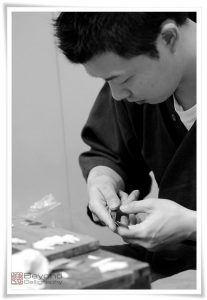

Unpei fude is also known as kami maki fude (紙巻筆, かみまきふで), or, maki fude, literally meaning “(paper) wrapped brush”. All of these types of brushes have at least one thing in common, a specific brush construction technique. Inside the tuft of the brush, the inner hair is bound and wrapped with Japanese hemp paper. This traditional way of making brushes was popular in Japan until the 17th century when scholar Hosoi Koutaku (細井広沢, ほそい こうたく, Hosoi Kōtaku, 1658 – 1735) introduced a new brush type which has been used right into the modern era. Today, for the most part, maki fude are utilized during Shinto (神道, しんとう, Shintō) religion ceremonies. However, they continue to also be used in calligraphy.

|  |

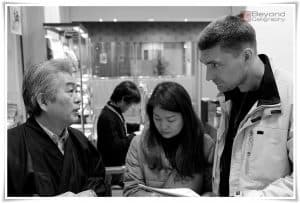

Quite recently I had a lengthy discussion with Fujino Junichi (藤野純一, ふじの じゅんいち), son of the owner of Hankeidou workshop, Mr. Juugosei Unpei (十五世雲平, じゅうごせい うんぺい, Jūgosei Unpei), and he kindly agreed to write an article that would be an in-depth introduction to the world of unpei fude. When I tell you that those two gentlemen are the only ones remaining in the world, who are skilled in the traditional ways of manufacturing maki fude, you will understand how thrilled I was. Additionally, he offered to submit pictures showing not only how the brushes are made, but also revealing the workshop interior, allowing us to venture inside. A rare treat indeed! For this reason, I am not going to explain in detail the particulars of the above mentioned types of unpei fude brushes, nor will I talk more about the history and secrets of this trade which today is on the verge of extinction. Instead, I will patiently wait for Fujino Junichi to send to me his article in Japanese, and I will translate it, so that you can read the story directly from the source.

The event that we attended in February was rather small, and the space was confined as other producers of Japanese folklore items were also attending. Nonetheless, as you can see from the pictures in this article, the spectrum of unpei fude types is quite wide. Hankeidou also produces standard brushes in regular use by calligraphers.

Since I did not possess any maki fude in my brush collection, I felt that it was a perfect opportunity to buy one. And so I did. I bought a small size maki fude. Its bottleneck-like tuft resembles that of a brush used for sutra copying, though the curving is more steep and abrupt. The hairs are extremely responsive and flexible, allowing for writing powerful lines with agility. I wrote many calligraphy works with this brush, and the range of scripts it is suitable for is quite broad and, includes oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun), cursive (草書, そうしょ, sōsho), semi-cursive (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho), and standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho). I believe that it would also perform well in kinbun (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metal”). It may be a bit too stiff for small seal script (小篆, しょうてん, shōten) whose lines are gently curved, with the energy retained within the round brush strokes and smooth endings. I am looking forward to trying out other brushes from the unpei fude family.

It is my great hope that this trade will continue and thrive, and that this old and nearly forgotten tradition will find its followers in the future. After all, this is what calligraphy art is all about. It is up to us to make sure that the next generation will continue what the previous ones cherished so much. Alas, today, we tend to lead fast and furious lives. Some of us struggle to find time for ourselves, squeezing in precious minutes between rush hour and a powernap to admire art on the glossy screens of our laptops. Yet thousands of years of knowledge cannot be simply zipped onto a floppy drive. Calligraphy, like the brushes made by Hankeidou workshop, requires our personal appreciation and close attention in order to survive.

Text: Ponte Ryūrui (品天龍涙)

Photography: Dave Gosine

English editing: Rona Conti

Japanese/Chinese editing: Yuki Mori