1. Meaning:

little, small

2. Readings:

- Kunyomi (訓読み): お-, こ-, さ-, ちい.さい

- Onyomi (音読み): ショウ

- Japanese names: いさら, こう, さざ, しゃお, ちいさ

- Chinese reading: xiǎo

3. Etymology

小 belongs to the 象形文字 (しょうけいもじ, shōkeimoji, i.e., set of characters of pictographic origin). It is a pictograph of scattered tiny objects, possibly shells or precious stones. It is a historical fact that at the end of the Neolithic Era (10,000 B.C. – 8,000 B.C.) ancient Chinese began to use shells as currency. The same currency existed in a later period, the Shang dynasty (商朝, pinyin: Shāng Cháo, 1600 B.C. – 1046 B.C.), i.e. the period when kinbun (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metals”) and oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun) were used for decorative and divinatory purposes, respectively.

The definition of the character 小 found in “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters” (說文解字, pinyin: Shūowén Jiězì) from the 2nd century C.E., compiled by Xu Shen (許慎, pinyin: Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.), a philologist of the Han dynasty (漢朝, pinyin: Hàn Cháo, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.), states that 小 represents small objects (such as shells or precious stones), or, more precisely, one object that was divided (the division is symbolised by “|”) into eight parts (hence the shape of 八 {はち, hachi, i.e. “eight”}, as shown in Figures 1 and 2).

Xiao Xu Ben (小徐本, pinyin: xiǎo xú běn), a revision of Shuowen Jiezi written by the Late Han dynasty scholar Xu Kai (徐鍇, pinyin: Xú Kǎi, 920 – 974 C.E.), supports the above mentioned definition of 小, by further explanation that the idea of dividing the “|” into eight parts, falls within the general principles of using currency. On the other hand, although it is speculative, some kinbun forms could suggest that 小 is a pictograph of a shell split into two parts, with “|” being either an ideograph of “dividing” or a pictograph of a knife.

Bokubun (卜文, ぼくぶん, lit. “divinatory text”, i.e. oracle bone script) forms of characters 小, such as 𧴪(pinyin: suǒ, i.e. “fragments”), 瑣 (pinyin: suǒ, i.e. “fragmentary”, “trifling”), etc., are all linked semantically. The 𧴪 stands out in particular, combining meanings of the characters 小 and 貝 (かい, kai, i.e. “shell”) in one.

Characters 肖 (pinyin: xiào, i.e. “similar”), 梢 (pinyin: shāo, i.e. “tip of the branch”), 削 (pinyin: xiāo, i.e. “to scrape”), etc. are all related to the meaning of “small fragments” (similar fragments, the most extreme fragment of a branch, to scrape off fragments of something).

4. Selected historical forms of 小.

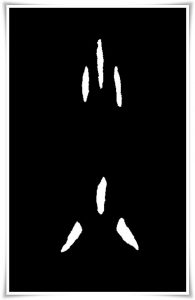

Figure 1. Oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun) forms of the character 小, Shang dynasty (商朝, pinyin: Shāng Cháo, 1600 B.C. – 1046 B.C.).

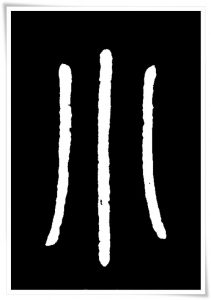

Figure 2. Ink rubbing of the small seal script (小篆, しょうてん, shōten) form of the character 小, found in the book “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters” (說文解字, pinyin: Shūowén Jiězì) from the 2nd century C.E., compiled by Xu Shen (許慎, pinyin: Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.), a philologist of the Han dynasty (漢朝, pinyin: Hàn Cháo, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.).

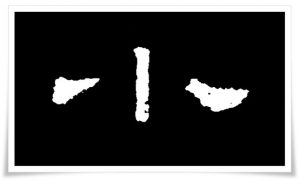

Figure 3. Ink rubbing of the mature clerical script (隷書, れいしょ, reisho) form of the character 小, found on the Stele of Zhang Jing (full name: 張景造土牛碑, Zhāng Jǐng zào tǔniǔ bēi), Han dynasty (漢朝, pinyin: Hàn Cháo, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.), 159 C.E.

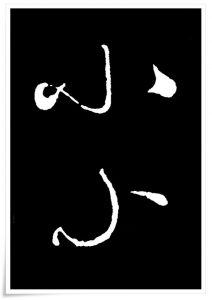

Figure 4. Cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) forms of the character 小, found in the writings of an outstanding ink painter and eccentric calligrapher of the Song Dynasty (宋朝; pinyin: Sòng Cháo, 960 – 1279 C.E.) Mi Fu (米黻, pinyin: Mǐ Fú, 1051–1107 C.E.), also known as Mi Fei (米芾, pinyin: Mǐ Fèi).

Figure 5. Ink rubbing of the standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) form of the character 小, from a stele whose name could be translated as follows: “Buddhist statue inscription for mourning the deaths of Sun Quisheng, Liu Qizu, and others” (孫秋生劉起祖等造像記, pinyin: Sūn Qiūshēng Liú Qǐzǔ děng zàoxiàng jì), erected in 502 C.E. The text is written in the extremely powerful style characteristic of the Northern Wei dynasty (北魏, pinyin:Bĕi Wèi, 386 – 534 C.E.), and it is attributed to Xiao Xianqing (蕭顯慶, pinyin: Xiāo Xiǎnqìng, birth and death dates are unclear). This stele is one of twenty calligraphy masterpieces carved into the rock of the famous Longmen Grottoes (龍門洞窟, pinyin: Lóngmén d ò ngkū), a cave in Eastern China.

Figure 6. semi-cursive script (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) form of the character 小, found in the calligraphy work entitled 澄清堂帖 (pinyin: Chéngqīng tángtiē) attributed to Wang Xizhi (王羲之, pinyin: Wáng Xīzhī, 303 – 361), often referred to as the Sage of Calligraphy (書聖; pinyin: shūshèng), Jin Dynasty (晉朝, pinyin: Jìn Cháo, 265 – 420 C.E.). The original work did not survive (in fact, none of his original works exist), and the rubbing was taken from a stele erected during the Ming dynasty (明朝, pinyin: Míng Cháo, 1368 – 1644 C.E.).

5. Useful phrases

- 小篆 (しょうてん, shōten) – small seal script

- 小文字 (こもじ, komoji) – lower case letters

- 小学校 (しょうがっこう, shōgakkō) – elementary school

- 小物 (こもの, komono) – accessories, small articles

- 小型 (こがた, kogata) – tiny, small size

Text: Ponte Ryūrui (品天龍涙)

English editing: Rona Conti

Japanese/Chinese editing: Yuki Anada