East Asian calligraphy flourishes in the absence of pride, goals or competitive desires. Its mastery comes from the negation of the material and the appreciation of the ethereal. It is a good feeling when one is rewarded for his or her efforts or achievements, but we need to remember to maintain a healthy distance from such distortions of purpose. If we do not, the path will become blurry, and eventually we will find ourselves lost.

Those of us who choose the path of Sho (書, しょ, i.e. “to write”; here: “East Asian calligraphy”) study calligraphy all of their lives, not to become recognized as masters, but rather to become one with art through attunement to its ancient principles. Calligraphy uplifts and allows us to ascend to another level of aesthetic consciousness.

The great philosopher Laozi (老子, pinyin: Lǎo zǐ, 6th century B.C.), often romanised as Lao Tsu, once said: “To know yet to think that one does not know is best. Not to know yet to think that one knows will lead to difficulty.” We must try to forget everything that we think we know and immerse ourselves in what we do not know.

Any passion undertaken without continuity and persistence is futile. It would be pursuing knowledge without wishing to go beyond. One cannot be forced to study, the intent must come from the heart. For me, calligraphy is not a hobby or even a way of life, it’s the air without which I cannot breathe. Those not acquainted with this art would think that there is nothing much to it, simply a few brush strokes on a white paper surface. Yet there is a vast universe hidden behind those ink traces.

There are multiple ways of studying calligraphy. One of the most important of them is the research and scholastic analysis of ancient manuscripts, so called koten (古典, こてん) in Japanese. Before even thinking of commencing rinsho (臨書, りんしょ, i.e. “copying [studying] classics”), one should focus on understanding what is to be studied. The very purpose of the calligraphy classics research group organized by my teacher (Master Kajita Esshuu [梶田越舟先生, かじたえっしゅうせんせい, Kajita Esshū Sensei]) is for us to realise what we do not know, for without such knowledge, we can never truly understand what we already know.

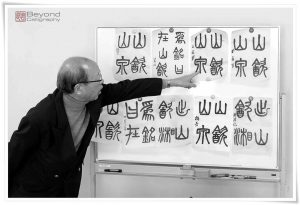

My teacher calls our meetings “Joys of the brush” (聿玩会, いつがんかい, Itsu gan kai). They take place every two weeks and are organized for those who are interested in deepening their knowledge of ancient masterpieces by great calligraphers. From my teacher’s vast library at his home, he always brings with him old books to show to us and speaks about them. Often he suggests to us subjects that we should pursue or issues that we should research.

The meetings are very similar to university courses where professors help students to navigate through seas with no horizon. We discuss mistakes and flaws in published books and dictionaries, errors made by other scholars, misprints, and sometimes we venture into the gray areas of characters missing from the ink rubbings (拓本, たくほん, takuhon) depicted in study books, missing due to the fact that the source (usually a stone stele) has been damaged.

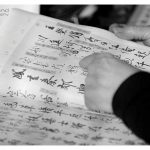

One excellent example of such a stone monument is the one referred to as Sekkobun (石鼓文, せっこぶん, i.e. “stone drum inscription”). During our last meeting, we spent over an hour discussing three characters in the text of poems composed and written by the Japanese Emperor Saga (嵯峨天皇, さがてんのう, 786–842, the 52nd emperor of Japan, 嵯峨天皇宸翰唐李嶠詩集 (さがてんのうしんかんとうりきょうししゅう, Saga Tennō shinkan tō ri kyō shishū, i.e. “Emperor Saga’s letters on the Tang Dynasty most distinguished poems”). He was one of the legendary Sanpitsu (三筆, さんぴつ, lit. “three brushes”) of the Heian period (平安時代, へいあんじだい, 794 – 1185). You can see in Figure 4 a book with glosses and notations which represent at least two generations of calligraphers who used that book for study purposes.

Each meeting, or series of meetings, is devoted to a certain manuscript. Nearly the entire year 2011 was devoted to letters in cursive script attributed to Wang Xizhi (王羲之, pinyin: Wáng Xīzhī, 303–361) of the Jin dynasty (晉朝, 265 – 420). It took us seven or eight months to practice and discuss the rinsho of his correspondence. Along the way, we learned various details about his life, as my teacher always brings with him copies of explanations of whatever it is that we study.

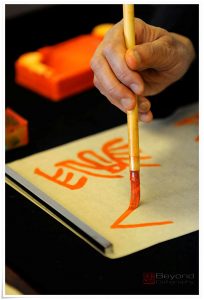

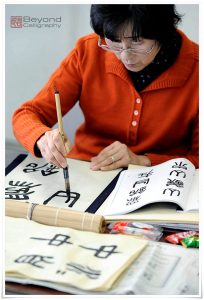

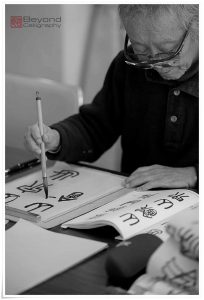

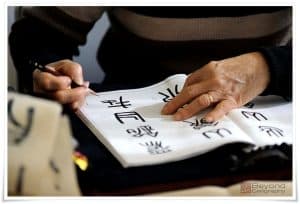

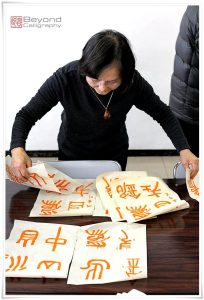

In the photograph, you are able to see us studying small seal script from the works of Wu Dacheng (吳大澂, pinyin: Wú Dàchéng, 1835 – 1902 C.E.), a famous seal carver and a seal script scholar of the Qing dynasty (清朝, pinyin: Qīng cháo, 1644 – 1912 C.E.). My teacher always writes with us and likes to move around and try to write with the brushes of other people. Now you can understand better the reason behind the name of our meetings. It is a critical error to get used to one set of the Four Treasures of the Study. One needs to try as many brushes, ink sticks, paper, and ink stones as possible. The combinations are infinite, and so are the results.

As you can see from the pictures, my closest friends are at least twice my age. In fact I do not know many young people in Japan. Generally speaking, the young generation neither respects nor is interested in old traditions, preferring to rush around rather than living by the Zen phrase, “Don’t just do something, stand there”.

Is this a requirement for younger people, to reject traditional values and embrace material possessions and life in the so called fast lane? I would say absolutely not. Life without depth is like depth without life, a dead sea with no visibility or oxygen to breathe, a toxic waste of useless memories. The older generation has more patience, less ego, more wisdom, and is much more open minded than I thought. Most importantly, they help to prevent the ongoing suffocation of the art of calligraphy, the ancient knowldge that is proudly hobbling on in the cold cyber-reality that is the present day world.