1. Meaning:

mountain; also: climax, critical point, speculation, guess, criminal case.

2. Readings:

- Kunyomi (訓読み): やま

- Onyomi (音読み):サン, セン

- Japanese names: さ, やの, やん

- Chinese reading: shān

3. Etymology

山 belongs to the 象形文字 (しょうけいもじ, shōkeimoji, i.e. set of characters of pictographic origin). It is a pictograph of a mountain rising up from the surface of the ground.

The sound and secondary meanings of the character 山 are strongly related to ancient Chinese myths. In “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters” (說文解字, pinyin: Shūowén Jiězì) from the 2nd century C.E., compiled by Xu Shen (許慎, Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.), a philologist of the Han dynasty (漢朝, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.), we read: 宣也。謂能宣散氣、生萬物也。(pinyin: Xuān yě. Wèinéng xuān sǎnqì, shēng wànwù yě.). This phrase is difficult to interpret. It tells us that 山 stands for “proclamation”, (Gods’) speaking ability (seen as) the dispersion of vital energy (clouds, i.e. life-nourishing rainfall), which sustains the existence of all living things (on Earth).

In the “Commentaries to Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters” (説文解字注, pinyin: shūo wén jiě zì zhù) by a Qing dynasty (清朝, pinyin: Qīng cháo, 1644 – 1912 C.E.) scholar, Duan Yucai (段玉裁, Duàn Yùcái, 1735 – 1815), we read that both 山 and 宣 (pinyin: xuān, i.e. “to proclaim”, “to announce (publicly)”) have rhyming sounds (due to their meaning related to Gods, and their proclamations [announced via natural phenomena, such as clouds and rains, etc.]), also known as stacking rhymes (畳韻, じょういん, jōin), often used in poetry based on Chinese characters. This theory is further confirmed in “Shi ming” (釈名, pinyin: Shì míng), a late Han dynasty book devoted to linguistics, in which we read that 山 has the same meaning (and also rhymes with) as 產 (pinyin: chǎn, i.e. “to reproduce”, “to give birth”).

In ancient China it was believed that mountains gave birth to the clouds, and from them originated the movement of the sky. As a result of such beliefs, mountains were often the central subject of prayers for rain. The meaning of “proclamation” is most likely an allegory for words of the gods in the form of rain in response to the prayers of people. Thus, each time we admire a mountain range during a rainstorm, we are listening to the words of Heavens.

Please also refer to the article on the etymology of the character 火 (ひ, hi, i.e. “fire”), and note the striking similarity of its ancient forms of the oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun) to the one of the character 山. Both characters are pictographs, though their etymology differs.

4. Selected historical forms of 山.

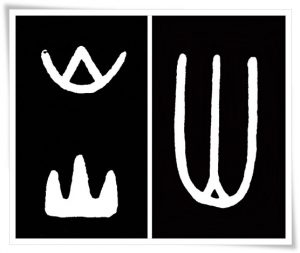

Figure 1. Various forms of the character 山 in oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun, c.a.1600 B.C. – 800 B.C.)

Figure 2. Great seal script (大篆, だいてん, daiten) forms of the character 山. Left hand side characters are in kinbun (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metal”) script. All examples are from works by a famous seal script scholar and calligrapher Wu Dacheng (呉大澂, pinyin: Wú Dàchéng, 1835 – 1902 C.E.), Qing dynasty (清朝, pinyin: Qīng cháo, 1644 – 1912 C.E.).

Figure 3. Clerical script (隷書, れいしょ, reisho) form of the character 山. This ink rubbing comes from the rock carving named Shi xia song (西狹頌pinyin: Shī xiá sòng), erected during the late Han dynasty (漢朝, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.), 171 C.E. Shi xia song is one of the most preferable texts for studying rinsho (臨書, りんしょ, i.e. “copying [studying] masterpieces”) of the clerical script.

Figure 4. Although I break here the historical chronology of script appearance, it is for a purpose of aligning four variants of the character 山, written by one calligrapher. The very top is a semi-cursive script (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) form of the character 山. The remaining three are in cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho). Note the change of stroke order in cursive script forms. Ink rubbings from works of Wang Duo (王鐸, pinyin: Wáng Duó, 1592 – 1652 C.E.), who lived on the verge of late Ming (明朝, pinyin: Míng cháo, 1368 – 1644 C.E.) and early Qing (清朝, pinyin: Qīng cháo, 1644 – 1912 C.E.) dynasties.

Figure 5. Ink rubbing of the standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) of the character 山, from a work titled Xiari you shicong shi (夏日游石淙詩, pinyin: Xiàrì yóu shícóng shī) by a poet and calligrapher Xue Yao (薛曜, pinyin: Xuē Yào, birth and death dates are unknown, though it is confirmed that Xue Yao was active during the end of 7th and beginning of 8th century C.E.), early Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907).

5. Useful phrases

- 火山 (かざん, kazan) – volcano

- 富士山 (ふじさん, Fuji san) – Mt. Fuji

- 山門 (さんもん, sanmon) – main temple gate

- 山羊 (やぎ, yagi) – mountain goat

- 沢山 (たくさん, takusan) – many, a lot