1. Meaning:

left (as in the opposite of “right”).

2. Readings:

- Kunyomi (訓読み): ひだり

- Onyomi (音読み): サ、 シャ

- Japanese names: あざ, さ, ささき, さざき, たすけ, ちゃ, ちょう, ひだり

- Chinese reading: zuǒ

3. Etymology

左 belongs to the category of characters known as 会意文字 (かいいもじ, kaii moji, i.e. a set of characters which are a combination of two or more pictographs, or characters whose meaning is based upon an abstract concept). 左 is a combination of two pictographs.

The top-left part of the character 左 is a representation of a pictograph of the left hand, today’s 𠂇 (さ, sa, i.e. pictograph of the left hand; ancient variant of the character 左), whose original meaning was “left hand”. As you can see (Figure 1), in oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, koukotsubun) the form of 𠂇 is a pictograph of the left hand, depicting a forearm and three fingers. The 工 radical in 左 is a simplified pictograph of a rod or a staff, used by ancient priests during a religious ritual. It was added to the character 𠂇 throughout the historical evolution of kinbun (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metal”) script.

To fully understand the meaning of the character 左, one should combine it with the one of the character 右 (みぎ, migi, i.e. “right”), on which a separate article was written (see here). The top part of 右 is a pictograph of a right hand, today known as 又 (ゆう/また, yū/mata; i.e. “again”, “furthermore”, “on the other hand”), whereas the bottom part is a pictograph of a vessel used for receiving blessings, namely 口 (さい, sai, i.e. “ritual vessel”), a vessel held by the diviners in their right hand during a ceremony.

口 (さい) is often mistaken for a different meaning for the pictograph, 口 (くち, kuchi, i.e. “mouth”). A separate article was written on this, it can be read here. Understanding the difference between those two pictographs is crucial for correct character classification and comprehension of the etymological theories of the Chinese writing system.

As an example I will use a popular book written by Dr. Kenneth G. Henshall (Ph.D. in modern Japanese literature, University of Sydney) titled “A guide to Remembering Japanese Characters”. Dr. Henshall is not a calligraphy scholar, which significantly impacts the depth of his research. Additionally, his book is clearly based on old data that precedes a revolutionary discovery in the field of the etymology of Chinese characters based upon oracle bone script found in 1899 in Anyang (安陽, Chinese: An yáng).

For instance, Dr. Henshall explains that the character 九 (きゅう, kyū, i.e. “nine”) is a pictograph of a bent elbow, as elbows in ancient China were used for indicating the number nine. He also provides a hand-written example of the kinbun form of the character 九 as an example of ancient writing. Recent research proves that the etymology of this character is completely different. The character 九 is in fact a pictograph of a female dragon, proven by research derived from its oracle bone form. There are many similar erroneous examples in his book. To read more on the etymology of the character 九、 please refer to a separate article, here.

The above example illustrates common errors committed by modern literature in regards to the origins of Chinese writing. Books available in English on the subject, and there are not many of them, are filled with serious flaws, among them are factual mistakes often based upon incorrect conclusions which are not supported by more recent research of oracle bone script forms as described above. In fact, the etymology of the character 左 presented in Dr. Henshall’s book is also incorrect.

The etymology of the character 左 can be further explored using the example of an ancient ceremony during which a priest swings a ritual object, first to the right and then to the left, praying for the forgiveness of the Gods and asking them for blessings. Thus, the ancient meaning of the word 左右 (さゆう, sayū, i.e. “left and right”, also “influence”, “control”, etc.) is “an act of praying to the Gods”.

Strongly associated with 左 is the character 佐 (さ, sa, i.e. “assistant”, “help”). It is a combination of 左 and 人 (ひと, hito, i.e. “human being”). Its meaning comes from the idea of praying for those who have passed away, hence the person radical 亻 (にんべん, ninben, i.e. “person radical”) + the character 左 which symbolizes the act of praying.

There is an inscription on the Eastern Zhou dynasty (東周, 770 – 221 B.C.) bronze vessel named 班𣪘 (Chinese: bān guǐ). The 異体字 (いたいじ, itaiji, i.e. “kanji variant”) of 𣪘 is 簋 (Chinese: guǐ), and it describes a bronze food vessel with a round mouth and two to four handles. The kinbun inscription on that vessel reads: 毛父左比,毛父右比 (Chinese: Máofú zǒu bǐ, Máofú yòu bǐ), i.e. “Máofú (a person’s name, most likely a highly ranked diviner, possibly a ruler’s adviser) is gesturing with his hands to the left, then to the right.” This phrase is describing a ritual in which the diviner Máofú is performing the above mentioned 左右, i.e. “act of praying to the Gods”.

The form of the character 左 used on some of the kinbun inscriptions is a combination of the pictograph of a left hand, and a 言部 (げんぶ, genbu, i.e. the 149th Chinese character radical, whose meaning is “word”, “to speak”). 言, used instead of 工, in the kinbun form of 左, symbolises an oath or vow offered to the Gods during the ritual, in return for their favourable blessings (Figure 3). On yet another vessel of the Eastern Zhou dynasty named 令彝 (Chinese: Lìng yí) the inscription reads, “We pray to the Gods for blessings on your official duties as well as your position as a government official.” On this inscription the very same form of 左 (𠂇 + 言) is found as the one shown in Figure 3.

4. Selected historical forms of 左.

Figure 1. Oracle bone script (甲骨文), form of 左, or more precisely its archaic form 𠂇, ca.1600 B.C. The original meaning of this kanji was the “left hand”.

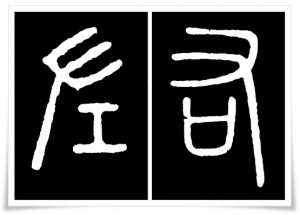

Figure 2. Pictograph of the left hand over a divination rod or sceptre (left), the form is found on 石鼓文 ( せっこぶん, sekobun, i.e. “Stone Drum Inscriptions”). The right side of the picture shows a pictograph of the right hand (又) over the sacrificial vessel (口) , the form is found in the 說文解字 (shūo wén jiě zì, i.e. “Explaining Simple Characters and Analyzing Compound Characters”), written by the philologist 許慎 (Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.).

Figure 3. The kinbun form of the character 左, merging the pictograph of the left hand 𠂇 with the character 言 (“words”), ink rubbing from a bronze vessel, early Western Zhou (西周, 1046 – 771 B.C.).

Figure 4. Ink rubbing of the clerical script form (隷書, れいしょ) of the character 左, taken from the late Han dynasty (後漢, 25 – 220 C.E.) stele 史晨碑 (Chinese: Shǐchén bēi), dated 169 C.E.

Figure 5. A cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) form of the character 左, from the ink rubbing from the work of 饒介 (Chinese: Ráo Jiè), a Yuan dynasty (元朝, 1279 – 1368) calligrapher.

Figure 6. Ink rubbing of standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) of the character 左, found in the calligraphy entitled 泉男生墓誌銘 ( Chinesae: Quán nán sheng mù zhì míng), dated 679 C.E. by the calligrapher 欧陽通 (Ōu Yángtōng, birth date unknown, died 691 C.E.), who was the son of the famous 欧陽詢 (Ōu Yángxún, 557 – 641) of the Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907).

Figure 7. Standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) from the character 左 found in 蘭亭集序 (Chinese: Lántíngjí Xù, also known as the “Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion”), attributed to 王羲之 (Wáng Xīzhī, 303 – 361 C.E.) of the Jin dynasty (晉朝, 265 – 420 C.E.).

5. Useful phrases

- 左折 (させつ, sasetsu) – left turn

- 左右 (さゆう, sayuu) – left and right, control, influence

- 左側 (ひだりがわ, hidari gawa) – left side

- 左手 (ひだりて, hidari te) – left hand