We often visit various calligraphy exhibitions, and would like to share some of our experiences with you. Our reports from calligraphy events will always be lavishly decorated with intriguing pictures, detailed explanations, and interesting stories that will often venture deep into the history of this amazing art, as well as both China and Japan.

This time we would like to invite you on a virtual tour to a seal carving exhibition that took place in Tokyo, in April 2011. Some 400 seal imprints were displayed, as well as around 70 antique seals carved by the Japanese and Chinese artists. We have picked up a few, to show you how profoundly deep and vast is the world of calligraphy, here in the Far East, and how closely it is connected to the spiritual and philosophical life of Asia.

Note: some readings of the phrases are given in Japanese, whereas others in Chinese.

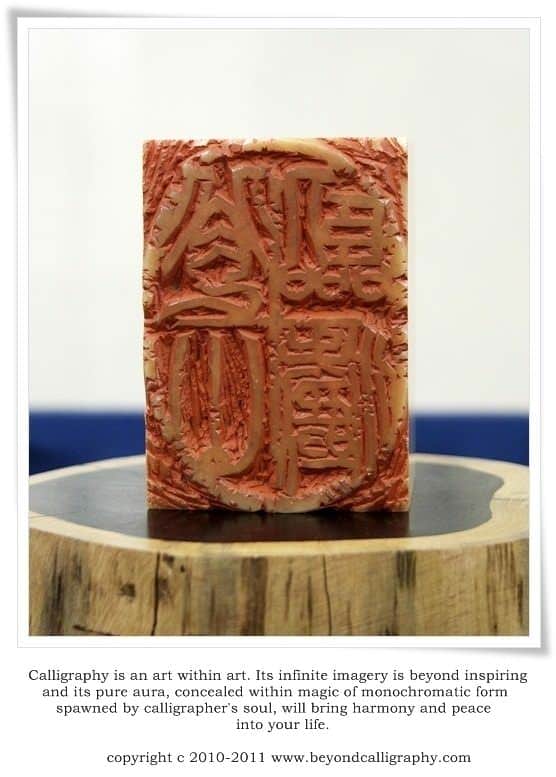

Seal carving is one of the ancient Chinese methods of “writing” calligraphy. The most primordial script, oracle bone script (甲骨文), was incised on bones prior to rubbing the text with cinnabar or charcoal. Later on, kinbun (金文), which together with oracle bone script belongs to the family of great seal script (篆書, tensho), was also (in later periods) “carved” with a stylus in a soft clay form prior to casting bronze vessels. Not without a reason is that seal carving art utilizes seal script as a medium.

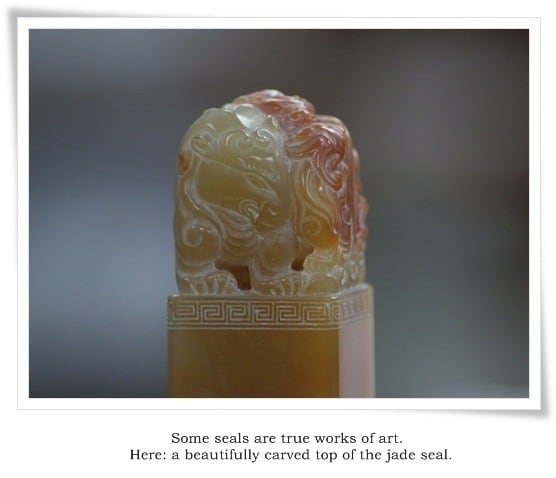

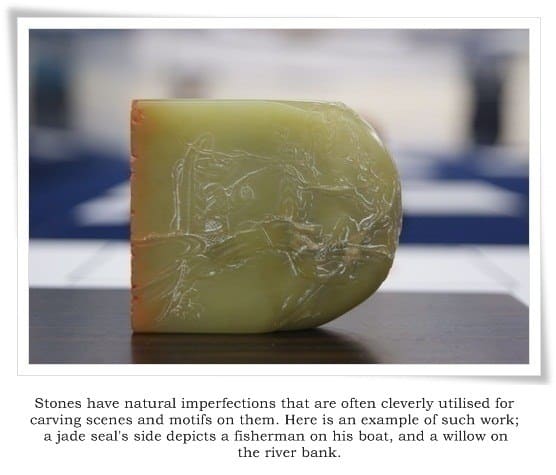

Seal carving requires not only vast calligraphy knowledge, but also an outstanding skill in sculpting. This is why the good seal carvers price themselves quite high, and are sought by many calligraphers.

Seal are used widely in everyday life of the Orient (businesses, official government seals, private seals, etc), but they will always have a symbolic meaning in the art of calligraphy.

Here are seals that we chose for you to read about. We hope you will find them as fascinating as we do.

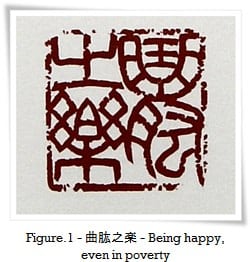

(Figure. 1) 曲肱之楽 (きょくこうのたのしみ, kyokugou no tanoshimi). Being happy, even in poverty. Literally: the joy (楽) of (之) resting on the very nook (曲) of one’s elbow (肱), instead of a pillow. This phrase brilliantly displays a symbolic nature of Chinese characters, and allows us to see how one can paint with words through calligraphy. It is not without a reason that calligraphy is often referred to as the “heart imagery”.

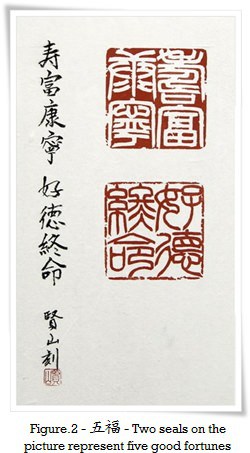

(Figure. 2) Two seals on the picture represent five good fortunes (五福, gofuku): 寿 (long life)・富 (fortune and richness (of one’s soul))・康寧 (tranquillity)・攸好徳 (love of virtue and good ethics)・考終命 (living a life according to the will of Gods, in consideration of the afterlife). Calligraphy is to soothe and calm the soul, bring joy and extinguish our worries. This is why calligraphers tend to write uplifting works, that are either comforting or bring smile and good luck into our lives.

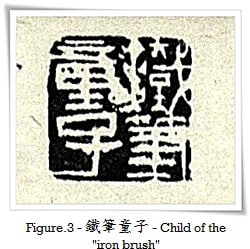

(Figure. 3) 鐵筆童子 (てっぴつどうこ, teppitsu douko) – Child of the “iron brush”. 鐵筆 is a reference to a steel knife (chisel) used in seal carving art, and it literally means “iron brush”. This is quite interesting that the name of the tool corresponds with calligraphy brush, which further shows how closely those two arts are related. “Child of the iron brush” is someone whose soul lives for and through the art of calligraphy (in this case in a form of seal carving).

(Figure. 4) 壷中日月長 (こちゅうにちげつながし, kochuu nichigetsu nagashi). It’s a Zen philosophy phrase which teaches us to fill our heart with both, the small and significant things, making it rich and our life enjoyable. In a world small as a jar the time passes in peace and harmony (壷 – lit. a “jar”; here: an allegorical meaning of our heart, that is not bothered with unnecessary thoughts), and all evil is routed around it. This phrase originated during late Han dynasty period (漢朝 (206 BCE – 220 AD) in China. A legend says that a certain old medicine man used to secretly hide in a small jar every night to sleep there. The jar sheltered him from the evilness of the world. One day, he let another person to enter the jar and rest, and the next day that person could not believe how tranquil the tiny world of the jar was. He then ordered a similar jar from the medicine man. Till today the jar symbolises our own peaceful universe, that each of us has to find by himself.

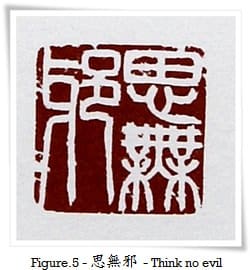

(Figure. 5) 思無邪 (しむじゃ, shimuja) – think no evil. Other reading could be “omoi yokoshima nashi” (おもいよこしまなし) – thoughts that bear no evil. Zen philosophy phrase that tells us to free our hearts not only of the evil thoughts,

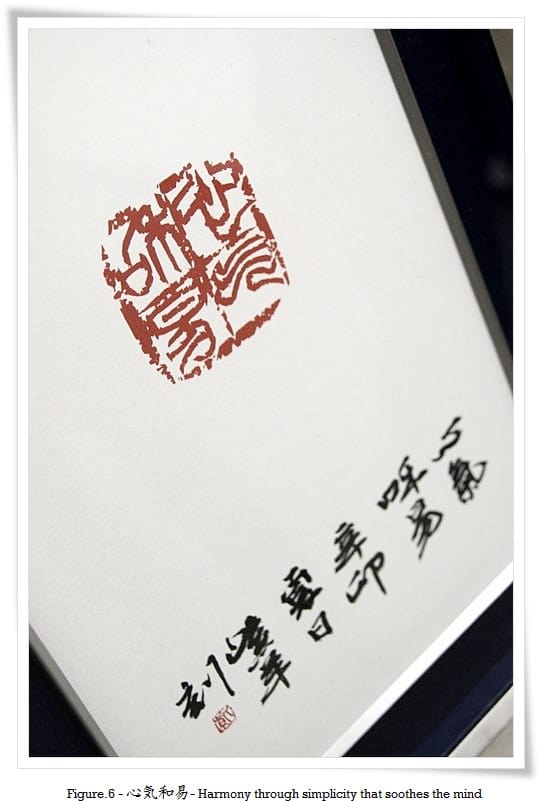

(Figure. 6) 心気和易 (しんきわい, shinki wai). The full phrase consists of five characters: 心気要和易, and it means that ( the well-being of) our mental state (心気) requires (要) harmony through simplicity (和易). Simplicity brings harmony, and it soothes the mind. This is no coincidence why admiring a Zen garden landscape, which is nothing else than rocks and sand, may have a healing effect on our soul.

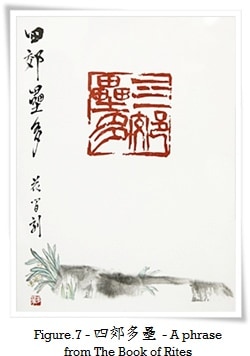

(Figure. 7) 四郊多壘 (Chinese reading: si jiao duo lei) – a phrase from one of the Five Chinese Classics of the Confucian cannon (Chapter: 曲禮上Quli Shang, Summary of the Rules of Propriety Part 1), written (as it is believed) by Confucius (孔夫子, 551 – 479 B.C.) himself during the Zhou dynasty (周朝, 1050-256 B.C.). It is known as the The Book of Rites

四郊多壘 is a reference to a city being surrounded from all four sides (四郊, lit. four outskirts), by numerous (多) armies of the enemy (壘, a reference to an army camp – 營壘). During Ming dynasty (明朝, 1368 – 1644 ) the exact same phrase was used by the defence minister Yu Qian (于謙; 398-1457), who led Chinese troops to defend the surrounded city of Beijing (北京) against the Mongolian army in 1449.

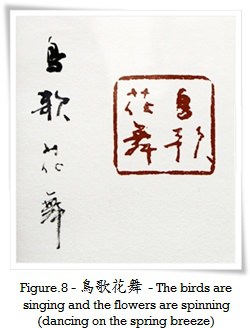

Seals are traditionally carved in seal script, especially those that are used as signature seals or leisure seals in calligraphy. Nonetheless, the seal on the picture (Figure. 8 ) bears characters carved in cursive script. We thought it is rather unusual, hence very interesting approach to seal carving art. Interestingly enough, the artist was a young girl (it is rather rare for women to carve seals) in her early 30’s.

It reads 鳥歌花舞 (とりうたいはなまう, Japanese: tori utai hana mau) – the birds are singing and the flowers are spinning (dancing on the spring breeze). A phrase taken from four verse poem compilation 豊楽亭遊春(ほ うらくていにはるをあそぶ (Japanese: hourakutei ni haru asobu), which could be translated into: a spring (season) floating over the pavilion of great joy)written by Ouyang Xiu (欧陽脩, 1007 -1072). It depicts first days of the spring season.

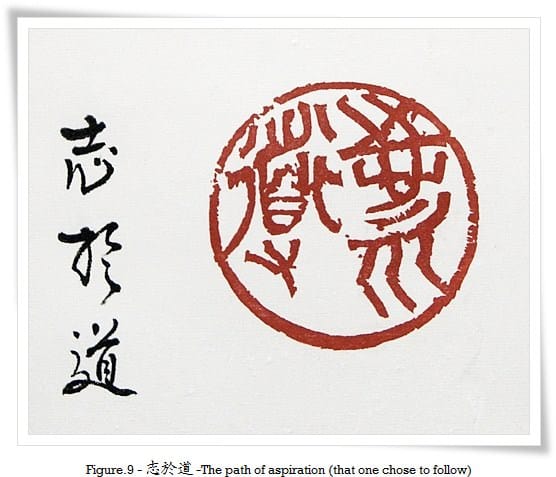

(Figure. 9) 志於道 (Chinese: zhi yu dao) – the path of aspiration (that one chose to follow). In this case the aspiration comes from the joy of studying calligraphy, which is also a path of life that leads to immortality of the soul of an artist, as he becomes one with strokes of the brush (or a chisel).

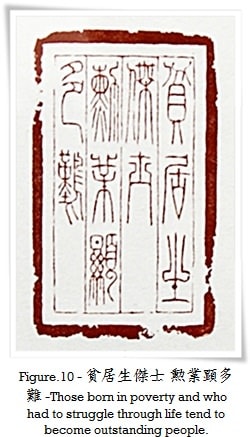

(Figure. 10) 貧居生傑士 勲業顕多難 (reading: 貧居(ひ んきょ) 傑(けっ) 士(し) を生(しょう) じ 勲業(くんぎょう) 多(た) 難(なん) に顕(あらわ) る, hikankyo ketsu shi wo shou,shi, kungyou ta nan ni tarawaru) – Those born in poverty and who had to struggle through life tend to become outstanding people. They emerge through overcoming various hardships and undertaking difficult tasks.

It’s a fragment of a poem by Saigou Takamori (西郷隆盛,, 1828 – 1877), who was possibly the most influential samurai in the Japanese history.

This seal is quite remarkanle; it requires a spectacualr control and skill to carve such thin lines in a stone, and at the same time preserve vigour and energy in the lines of the characters.

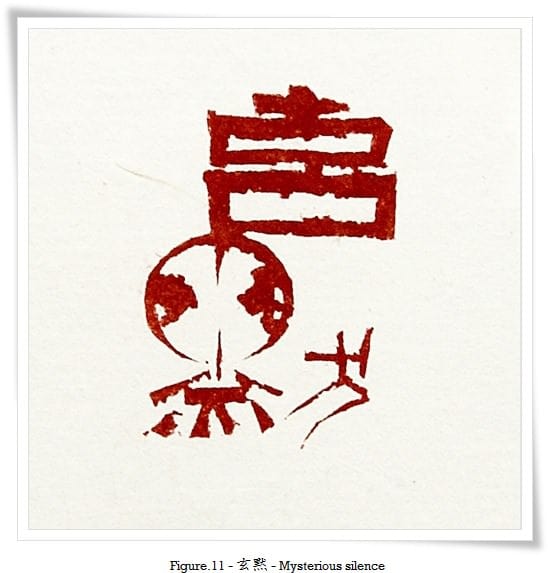

(Figure. 11) 玄黙 – (げんもく, genmoku) – mysterious silence. It can be interpreted freely. For me, it will always be the spiritual “silence” of the brush chasing my dreams on paper, and the silent whisper of the ink, telling me stories thousand years old.

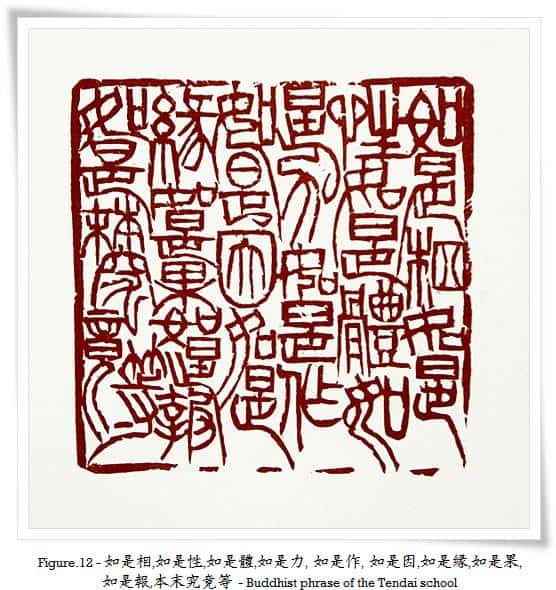

The full text on the seal (Figure. 12) reads: 如是相,如是性,如是體,如是力, 如是作, 如是因,如是縁,如是果,如是報,本末究竟等. This phrase (or idea) is a foundation of Buddhist teachings of the Tintai (天台宗) tradition, an ancient Buddhist school in China, and it is attributed to the school founder – monk Zhiyi (智顗,538-597 CE). The main doctrine of the Tintad sect was一念三千(Japanese reading: いちねんさんぜん, ichinen sanzen), which may be interpreted as: “within single thought there are three thousands (virtually: infinite number) of existences”.

- 如是相 (ru shi xiang) – every existence has its appearance

- 如是性 (ru shi xing) – every appearance has its nature

- 如是体 (ru shit ti) – every nature has its substance (body)

- 如是力 (ru shi li) – every substance has its ability (force)

- 如是作 (ru shi zuo) – every force tends to act externally (interact with environment)

- 如是因 (ru shi yin) – all the existing things are countless, and they all interact with each other. No things are unrelated and they all are bound by complex relations. Those relations are a reason (因) of many phenomena that take place in the Universe. Those reasons are infinite.

- 如是縁 (ru shi yuan) 」 – every reason is related (縁) to certain conditions that need to be met for a phenomena to appear. We cannot see the air till it condenses due to temperature variations, and appears in a form of a dew on the leaves.

- 如是果 (ru shi guo) – every reason and related conditions produce an effect (果), just like the dew on the leaves.

- 如是報 (ru shi bao) – the result remains as an achievement.

- 本末究竟等 (ben mo jiu jing deng) – All of the above takes place in the universe at all times, from its beginning to its end. Those happenings are complex and entangled with one another, and in result, it is difficult to say which one is the cause and which one the reaction. It shows that there are many things that human mind does not understand. Nonetheless these are the origin of all things and happenings in the universe, regardless of the type of things, action or situation, and all of it boils down to one simple rule: 諸法実相 (zhu fa shi xiang, “the reality of existing things”) – i.e. all things are governed by the laws of the Universe. 本末究竟等 means, that from the beginning (本) of the Universe until its end (末), it will be, after all (究竟), ruled by the same (等) laws (法).

The seal itself is quite extraordinary. The phrase is rather significant, but most importantly I would like you to realise how much work and planning it must have took to carve it. One single mistake and the whole process would need to be started all over. I reckon, it must have taken approximately 5-7 hours of carving. It is possible that the effort and focus invested into creating this spectacular work of art is symbolic, and goes well along with the meaning it represents. The final result is the effect of many complex reasons and conditions that had to take place or appear, for it to be completed. Extensive knowledge of calligraphy is one of them.

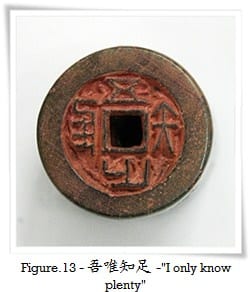

(Figure. 13) 吾唯知足 (われ、ただ足るを知る、ware tada taru wo shiru) – a phrase of Zen philosophy, carved on a famous stone receptacle with continuously flawing water for ritual purification, which is located in the Ryouanji Temple (龍安寺) in Kyoto, Japan. The stone is named (蹲踞, tsubai), which means “to crouch”, as one needs to crouch and kneel, to be able to reach for the water (showing respect). Four characters share the same radical (kanji compound), which is 口 (くち, kuchi – a mouth), and it also serves as the water container. Similarly on the pictured seal, 口 is located in its centre, and it is being “shared” by all four characters. It further emphasises the meaning of the phrase: “I only know plenty” (吾唯知足), or in other words – do not be dissatisfied with what you are or what you have, and always fill your heart with positive thoughts, as what one has is all what one needs. The phrase deeply touches on non-materialistic teachings of Buddhism. In the temple, there is a world-wide famous Zen stone garden (石庭, せきて、sekitei), build in 15th century C.E., where one cannot observe more than 14 stones, while standing at any place on the temple terrace. This suggests us, once more, to rejoice with what we have. Perhaps, something to reflect upon in nowadays rush.

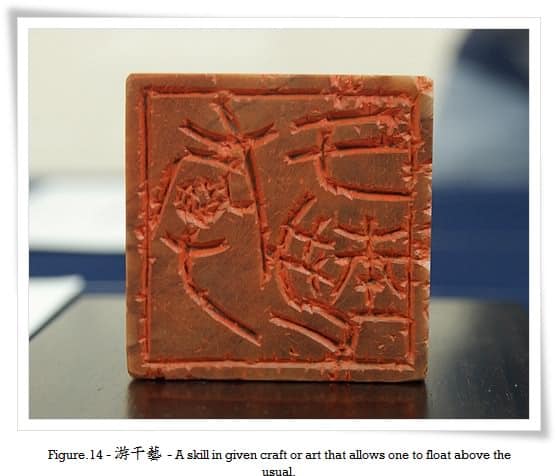

(Figure. 14) 游干藝 (ゆうかんげい, yuu kan gei) – this phrase is rather ambiguous and quite tricky to interpret. I could imagine that it is a reference to a skill (藝) level in given craft or art (here it is seal carving), that allows one (干) to float or roam (游) above the usual. 干 has many meanings, in both Chinese and Japanese, so as with poetry, the interpretation is often in the hands (or hearts rather) of the reader.

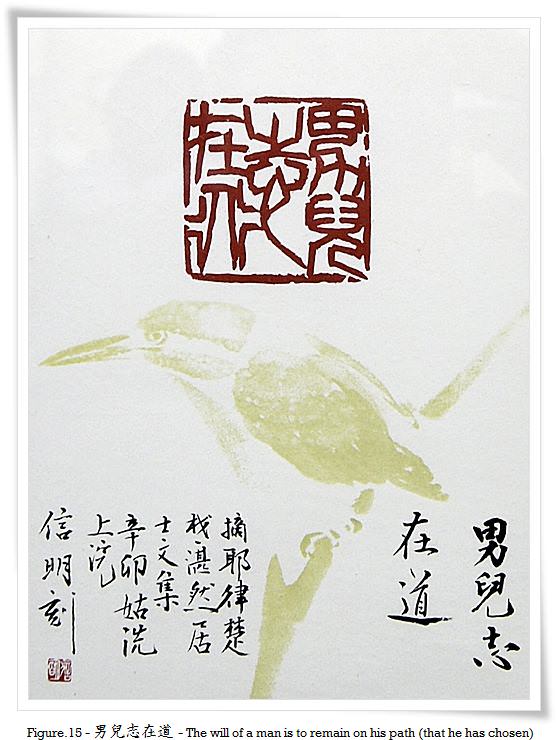

(Figure. 15) 男兒志在道 (Chinese reading: nan er shi zai dao) – the will of a man is to remain on the path (he has chosen). It’s a keystone of many oriental disciplines, such as martial arts or calligraphy (which, on a side note, have much in common). If one does not persevere, his efforts will be worth nothing. Distantly, it points at a conclusion, that the reward for holding one’s path is the reward on its own, as it allows one for bettering himself.

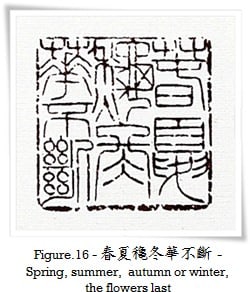

(Figure. 16) 春夏穐冬華不斷 – Spring, summer, autumn or winter, the flowers last. This is (in my opinion) a phrase written by the author of the seal, and, to my understanding, it means that his happiness blooms despite of the time of the year (despite up’s and down’s). Calligraphy can hibernate worries and deflect evil, which is why most of calligraphers reach very old age in health and spiritual happiness. Admiring calligraphy can have a healing effect on your soul. Scientists have proved, that calligraphy is the most effective recipe for longevity (and ranks above any of the Chinese spiritual disciplines, including Tai Chi).

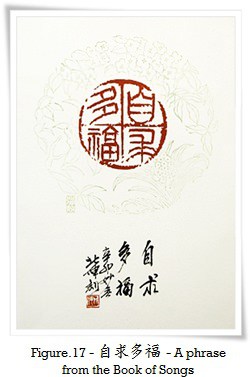

(Figure. 17) 自求多福 (Chinese reading: zì qiú duō fú) – demanding from yourself (to do more, in order to become better), will being you more happiness than if you ask a stranger for the same. The phrase comes from Shi Jing (詩經), The book of Songs, an early collection of Chinese poems and one of the Five Classics of Confucianism (五經, Wu Jing). The other were The Book of History (書經, shu jing), The Book of Rites (禮記, li ji), which was mentioned above, The Book of Changes 易經、yi jing), and The Spring and Autumn Annals (春秋, chun qiu). The Book of Songs is the earliest existing collection of Chinese poetry and songs. It comprises of over 300 compositions, some possibly from as early as 1000 B.C.

We hope you enjoyed this read. Please feel free to leave a comment, suggestion or simply ask a question. You may also contact us directly via e-mail. We are constantly adding new content to our sites (please visit us also at www.beyondcalligraphy.com). If you would like to learn more about Far Eastern calligraphy, as well as Chinese writing system, please visit us again.