Originală în limba engleză poate fi găsit aici.

Dreaming Japan eons before I ever set foot on its soil, from the time I was in college studying ceramics and painting I was mesmerized by Japanese scrolls, the essential black and white mysteriously beautiful forms brushed upon tactile surfaces, then mounted and hung in soft-lit rooms of museums. Envisioning Japan from books and objects, I dreamed of studying calligraphy in its proper setting.

Love and youth has a way of re-shaping dreams. Had I not found the former and not been the latter, I likely would have found a way to adventure to Japan at that time. Instead, I received a letter from Japan from my friend and advisor at Antioch College, Karen Shirley, a potter three years my senior, my “senpai”. “Be sure to come to Mashiko and see Japan before all of the wood burning climbing kilns are no longer allowed because of pollution.” It was 1964. I had graduated that May and was in Boston. I filed her advice away for later and set about pursuing my passion which began with brushes.

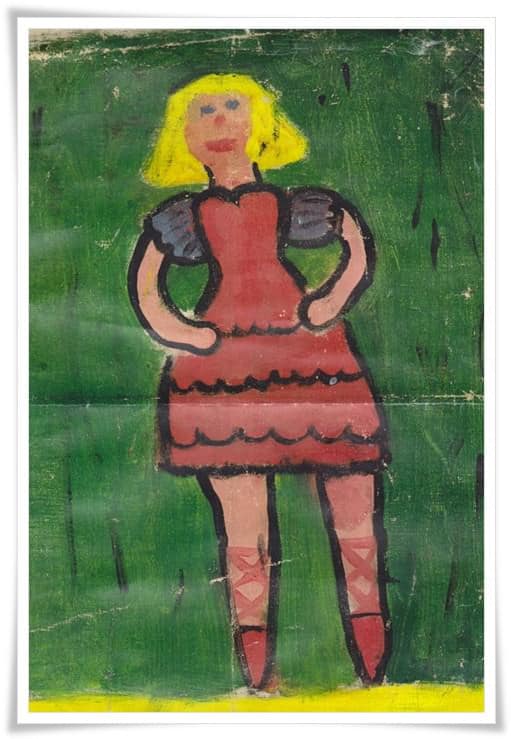

The resumes of Japanese Calligraphy Masters usually start with the young age at which they began their studies, often with a relative. As a Western counterpart, I can only point to my parallel path, my taking up of a different kind of brush. The desired image of my five-year old self, painted with oils on an un-stretched canvas, somehow miraculously survived. It was painted at the studio of my aunt, Helen Jacobson, a fine painter and a beautiful woman. She was blond haired and blue-eyed, always elegantly dressed, I was brown and brown. Vividly remembering painting in her cavernous space where my imagination soared, I decided at that moment my future path. Wishing to be an artist ballerina when I “grew up”, the incongruity of painting in a tutu never occurred to me (Figure 1).

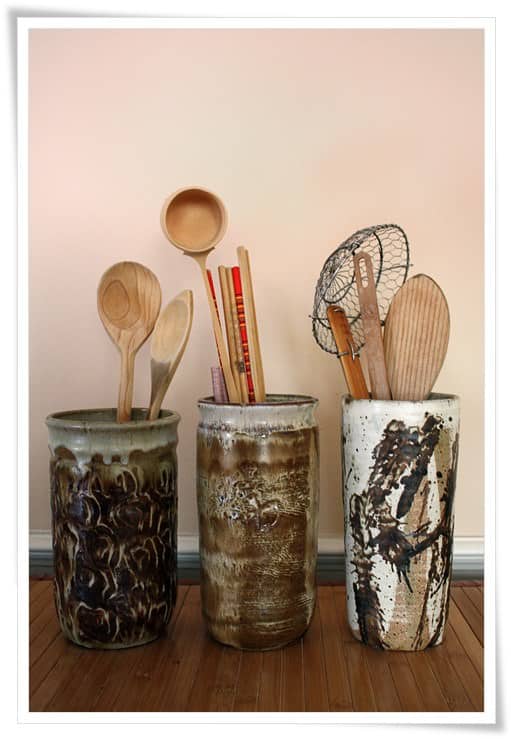

My encounters with brushes continued through college. When I landed in Boston I set up a painting studio, but a place to do ceramics was more challenging. However, Boston, being a large cosmopolitan city of many universities and colleges, had a few places where one could arrange access to, if not a wood fired Japanese climbing kiln, at least a gas fired kiln with its reduction and interesting amazing possible glazes . The School of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts provided that for me. Wheel thrown vases, meant for only one rose, were decorated by patterning and overlaying glazes (Figure 2). Among the pieces created, the cylinders I threw and fired in the gas kiln could be vases for many roses, but I have been using them for kitchen utensils all these years (Figure 3).

Japanese brushes were in use for decorating with slip under glazes, I had tried that technique. In the hands of a skilled potter and artist, calligraphic strokes could be made. At the time my attempts at such strokes were not authentic as they were without the bones required, the learning of calligraphy. A photograph taken just a few years ago with brushwork by Masakazu Kusakabe illustrates perfectly the synthesis of calligraphy as decoration on clay (Figure 4). He is a Master, a potter from Fukushima who travels the world instructing generously and organizing the building of his self-designed smokeless eco-conscious wood burning kilns.

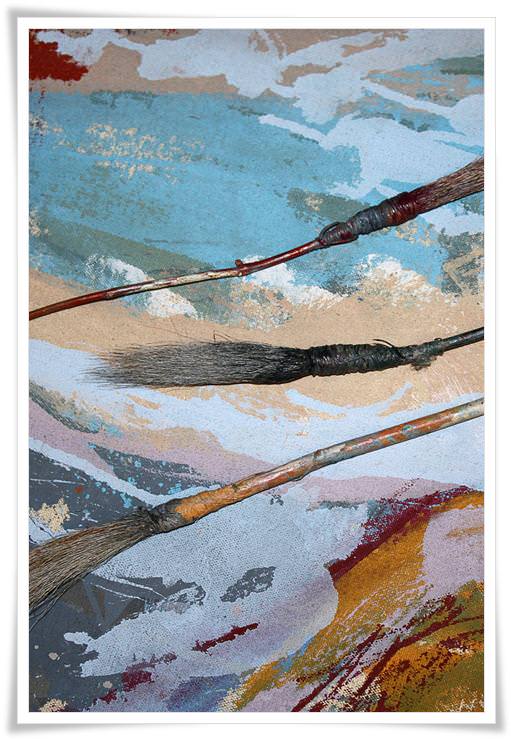

My desire for making my own distinct marks required a different approach. Bringing the painter in me to the task, I set about making some brushes. Before the internet there were libraries, I looked in books for advice, then discarded most as impractical and simply set about “doing a Nike” as in “Just do it.” Thinking of where to find a source of animal hair/fur used for making brushes, I looked for a shop with fishing supplies. The so called “bait and tackle” shops sell this for “fly tying”. One could buy live worms as well, but I did not need those. I purchased three deer tails with apologies to all Bambis and had a close look at their shape to decide where to cut and gather the hair. Laying out the hair on a piece of paper to approximate a tapered brush and coating the upper fourth part with elmers glue, a common liquid white glue, I lay down strong, stiff wood for a handle. Rolling the hair around the handle, I fashioned a somewhat awkward but seemingly serviceable brush. To keep the hair wrapped around the handle, along with the glue, I wrapped dental floss. These were certainly not “maki fude” brushes.

The first attempt was iffy since the dental floss seemed to slip until I figured out that I should use un-waxed dental floss. Such are the trial and error adventures when one sets out to do something unconventionally or perhaps non-traditionally. The successful brushes (Figure 5) became my companions for decorating ceramics which I was doing simultaneously with painting. Each brush has its own unique shape and the strokes/marks which emerge are likewise depending upon how one uses it. The only work remaining from that period is a platter, happily the others were purchased (Figure 6).

In 1969, I was invited to teach for one semester at Brandeis University under a program entitled “flexible curriculum” which offered three courses: Homosexuality, witchcraft, and ceramics, interesting choices particularly for that era. From that time forward I taught ceramics, administrating a department in Boston with a gas kiln, organizing workshops with Paulus Berensohn , Vivica and Otto Heino, and Gerry Williams, among others. I also did one other creative project, and in preparation for the culmination of that project, I rented a painting studio away from my place of residence. While I continued to teach ceramics, from 1970 forward, I devoted my art to painting only.

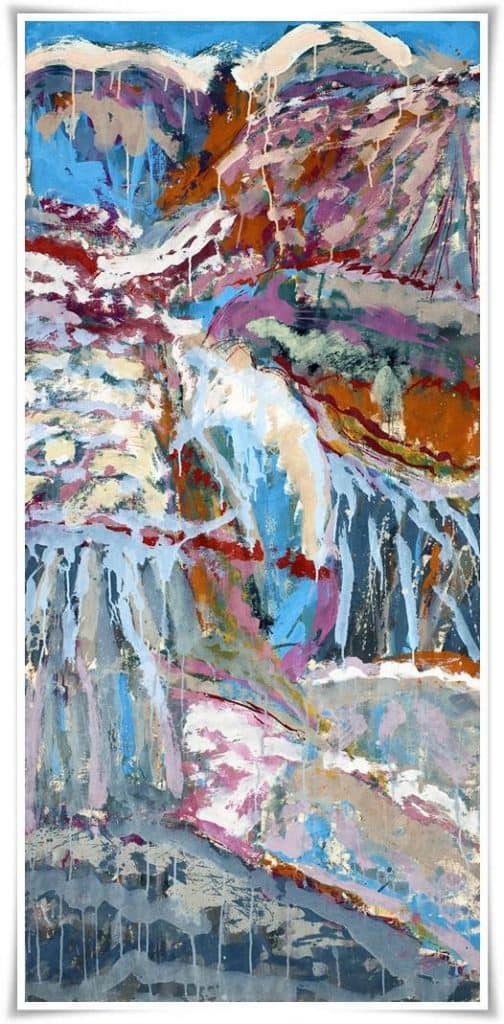

It was a few years later, having returned from a getaway sojourn, that I was anxious to get back to the studio and to paint my experience. Pre-visualization of ideas or desired visions often coincide, and some paintings simply paint themselves. Such was the case with Wilton Waterfall, 1976, a responsive painting after having spent an idyllic three days, a ladies only, mothers fleeing to nature, each of the four friends having a room of our own and time to explore in New Hampshire without children, our “creative projects”. Mine were then one and six years old. The deer-tail brush made for ceramics decoration seemed a perfect fit for making marks/painting over the surface of canvas. Thus, acrylic paint became the brush’s new companion. (Figure 7). (Figure 8).

Over the years, growing as an artist, the thought of the now rather distant past dream never left. While reveling in color and paint and later exploring work using handmade paper pulps, the vision of Japan continued to come front and center. Dividing the space, placement, the glory of the simplicity of Japanese calligraphy, eliminating the unnecessary and getting to the essence of the black and the white and in between seemed attainable at last. Seeking adventure, finding a way, I secured a job teaching English, sold my car, rented my apartment, told my two creative projects, now 28 and 23, to come and visit, and I departed for Japan. It was summer, 1998.

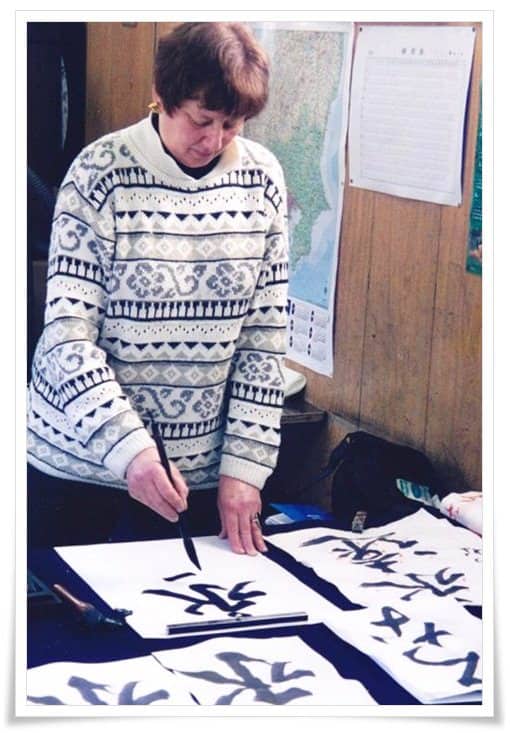

While I spoke no Japanese, while it took quite a lot of work to convince my bosses that I could teach and study, thanks to an adult student, I found a calligraphy Master willing to teach me. It was March of 1999, I had only three months left on my work visa.

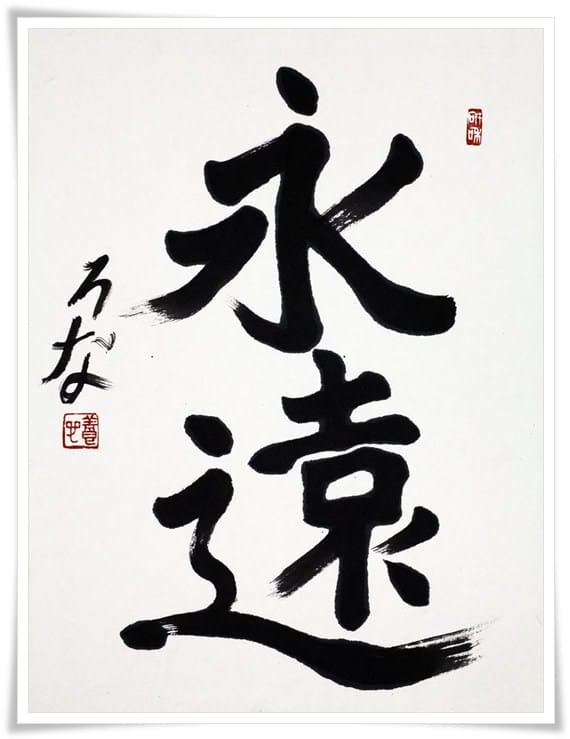

The most precious moment held forever in memory was of holding a brush for the first time in Kobayashi Sensei’s studio, the long journey only just begun. It was the first, but definitely not the last time in Japan that quiet tears of joy would travel slowly down my cheeks. I was home (Figure 9). (Figure 10)