1. Meaning:

hand

2. Readings:

- Kunyomi (訓読み): た-, て, て-, -て

- Onyomi (音読み): シュ, ズ

- Japanese names: does not appear in Japanese names

- Chinese reading: shŏu

3. Etymology

手 belongs to the 象形文字 (しょうけいもじ, shōkeimoji, i.e., set of characters of pictographic origin). It is a pictograph of a hand, shown from the wrist, and with five fingers attached to it.

The definition of the character 手 found in “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters” (說文解字, pinyin: Shūowén Jiězì) from the 2nd century C.E., compiled by Xu Shen (許慎, Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.), a philologist of the Han dynasty (漢朝, pinyin: Hàn Cháo, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.), suggests that it is a pictograph of a palm that is closed in a fist. This would explain why the finger that would appear to be the middle finger is curved (see Figure 1). If you fold your palm into a fist, then press the thumb against the remaining four fingers, you will understand the concept behind the pictograph. It is very clear in kobun (古文, こぶん, i.e. “ancient writings of Shang (商朝, 1600 – 1046 B.C.) and Zhou (周朝, 1046 – 256 B.C.) dynasties, such as oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun) forms, and earlier markings on pottery. Refer to Figure 1.

Unfortunately, since the oracle bone script forms either do not exist or have not yet been deciphered, we have to rely upon the explanation found in the above mentioned book.

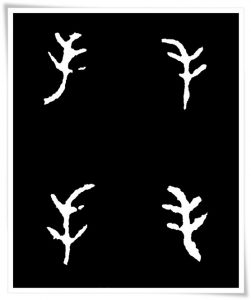

Curiously enough, the kinbun (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metal”) forms of the character 手 differ slightly from those found on ancient pottery. They resemble an open palm and not a clenched fist. The middle finger is not so steeply curved (Figure 2).

Although the modern form of the character 手 may be somewhat misleading (6 fingers), the “hand” radical 扌 still resembles the ancient pictographs. One must remember that the cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) forms of 手 preceded the standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) forms. The upper stroke in standard script is the result of aesthetical modification made to the first stroke in the cursive hand which imitates the “middle finger”.

4. Selected historical forms of 手.

Figure 1. Kobun form (古文, こぶん, lit. “ancient text”) of the character 手, found in the book “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters” (說文解字, pinyin: Shūowén Jiězì) from the 2nd century C.E., compiled by Xu Shen (許慎, Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.), a philologist of the Han dynasty (漢朝, pinyin: Hàn Cháo, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.).

Figure 2. Various ink rubbings of kinbun (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metal”) forms of the character 手, taken from various Eastern Zhou dynasty (東周, pinyin: Dōng Zhōu, 770 – 221 B.C.) bronze food vessels with a round mouth and two to four handles, known as “gui” (簋, pinyin: guǐ).

Figure 3. A very interesting form of the character 手, from the calligraphy 馬王堆帛書老子乙本 (pinyin: Mǎwángduī bóshū Lǎo Zǐ yǐběn), discovered in the Mǎ Wángduī archaeological site in 長沙 (pinyin: Chángshā), written by the legendary Laozi (老子, pinyin: Lǎo Zǐ, 5-4th century B.C., though some sources suggest 6th century B.C.), the founder of Taoism. Ink on silk, early clerical script (隷書, れいしょ, reisho). Note that the middle finger is virtually non-existent.

Figure 4. Cursive (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) and semi-cursive script (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) forms of the character 手 from calligraphy masterpieces by the ink painter and calligrapher of the Song Dynasty (宋朝; pinyin: Sòng Cháo, 960 – 1279 C.E.) Mi Fu (米黻, pinyin: Mǐ Fú, 1051–1107 C.E.), also known as Mi Fei (米芾, pinyin: Mǐ Fèi).

Figure 5. Standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) form of the character 手, found in the stele Yan Qinli bei (顔勤禮碑, pinyin: Yán Qínlǐ bēi) by Yan Zhenqing (顔真卿, pinyin: Yán Zhēnqīng, 709 – 785) of the Tang Dynasty (唐朝, pinyin: Táng Cháo, 618 – 907 C.E.).

5. Useful phrases

- 手紙 (てがみ, tegami) – a letter

- 手術 (しゅじゅつ, shujutsu) – surgery

- 右手 (みぎて, migi-te) – right hand

- 手作り (てづくり, tezukuri) – hand-made

- 手本 (てほん, tehon) – an example written by a calligraphy teacher

Text: Ponte Ryūrui (品天龍涙)

English editing: Rona Conti

Japanese/Chinese editing: Yuki Anada