1. Meaning:

chance, hope, idea, look at, opinion, see, visible

2. Readings:

- Kunyomi (訓読み): み.える、 み.せる、 み.る

- Onyomi (音読み): ケン

- Japanese names: does not appear in Japanese names

- Chinese reading: jiàn

3. Etymology

見 belongs to the 象形文字(しょうけいもじ, shōkeimoji i.e. set of characters of pictographic origin). It is a pictograph of a human with an exaggerated eye, indicating a person watching something from afar, while kneeling (see Figures 1 and 2).

The kinbun (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metal”) inscription on a stunningly beautiful three-legged bronze vessel named 匽侯旨鼎 (Chinese: Yǎn hóu zhǐ dǐng) from 11th – 10th century B.C., describes the relationship between the kings of the Western Zhou dynasty, 西周, 1100 – 771 B.C.) and the vassal clan of 燕 (Chinese: Yān). Part of the inscription bears a reference to the magnificence (見事, みごと, lit. “a thing to look at”, i.e. something splendid) of the earliest rulers of the Zhou dynasty (周朝, 1046 – 256 B.C.). Another inscription containing the character 見 suggests (someone seeking) an “audience” (謁見 (えっけん, ekken) with the noblemen of Zhou. This interpretation of the text leads us to the conclusion that the origin of the shape of the character 見 (looking from afar while kneeling) was derived from a figure of a kneeling person, looking from afar at the ruler and expressing gratitude.

An inscription on another artifact (or more precisely, a bronze bell) from the same historical period, named 宗周鐘 (Chinese: Zōng zhōu zhōng), describes how King Li (厲王, Lì Wáng) modeled himself on the great deeds of his ancestor, King Wu (武王, Wǔ Wáng), the founder of the Zhou dynasty, and further supports this theory of the origin of the shape of the character 見. The inscription reads that when the rebelling southern state of 濮 (Chinese: Pú) was forced to surrender to the King of Li, the emissaries sent to the capital of Zhou begged for peace. They were assisted by emissaries from 26 other states (from the southern and the eastern parts of the Zhou). The shape and the meaning of the character 見 carved on the inner side of the 宗周鐘 is consistent with the one on 匽侯旨鼎.

Summarizing, the earliest meaning of the character 見 was a deed involving kneeling and facing another person, and spiritual and respectful exchange or discussion, which was expanded to “looking” in general in later stages of the evolution of this character.

4. Selected historical forms of 見.

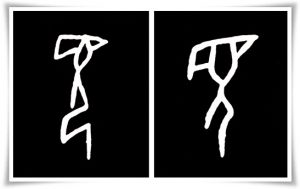

Figure 1. Various forms of the character 見 in oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun, c.a.1600 B.C. – 800 B.C). Note the left-hand side character is a pictograph of a kneeling person, whereas the right-hand side one is a bent person bowing.

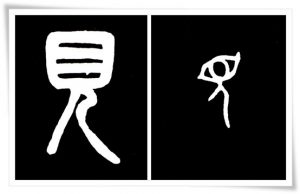

Figure 2. Seal script (篆書, てんしょ, tensho) forms of the character 見. The left-hand side form comes from one of the works by a famous seal script scholar and calligrapher 呉 大澂 (Wú Dàchéng, 1835 – 1902 C.E.). The right-hand figure is an ink rubbing of the inscription on the above mentioned bronze bell, 宗周鐘 (Chinese: Zōng zhōu zhōng).

Figure 3. Clerical script (隷書, れいしょ, reisho) form of the character 見. This ink rubbing comes from the damaged stele 朝侯小子碑 (Chinese: Cháo hóu xiǎo zǐ bēi), erected during the Han dynasty (漢朝, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.)

Figure 4. Cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) form of the character 見, found in the 急就章(Chinese: Jǐ jiù zhāng), composed by the Western Jin dynasty (西晉, 265-316 C.E.) scholar and calligrapher 索靖 (Chinese: Suǒ Jìng, 239 – 303 C.E.), who was a grandson of the great 張芝 (Chinese: Zhāng zhī, birth date unknown – 192 C.E.). 急就章 was one of the very first Chinese books, aimed at teaching proper written forms of characters. The form you see in the picture is a rinsho (臨書, りんしょ, i.e. “copying masterpieces”) attributed to Kūkai (空海, くうかい, 774-835), the Buddhist monk, scholar and poet, who was possibly the greatest Japanese calligrapher of all time, and lived during the Heian period (平安時代, へいあんじだい, 794 – 1185 C.E.).

Figure 5. Ink rubbing of the standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) of the character 見, taken from the Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907) stele entitled 皇甫誕碑 (Chinese: Huáng fǔ dàn bēi). The text was written by the famous Tang calligrapher 欧陽詢 (Ōu Yángxún, 557 – 641), whose standard script in particular was outstanding.

Figure 6. Semi-cursive script (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) form of the kanji見. This particular ink rubbing comes from the calligraphy 史事帖 (Chinese: Shǐ shì tiē), attributed to 欧陽詢 (Ōu Yángxún, 557 – 641) of the Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907), although calligraphy historians are still debating the authenticity of the signature, due to the unusual semi-cursive style that was applied in this work.

5. Useful phrases

- 発見 (はっけん, hakken) – discovery

- 見本 (みほん, mihon) – sample, specimen

- 見事 (みごと, migoto) – splendid

- 意見 (いけん, iken) – opinion, view

- 見当 (けんとう, kentō) – estimate, guess