1. Meaning:

empty, sky, vacant, vacuum, void

2. Readings:

3. Etymology

空 belongs to the 形声文字 (けいせいもじ, keiseimoji, i.e. phono-semantic compound characters). This is by far the largest group of Chinese characters, encompassing about 85 – 90% of all kanji, which are constructed of semantic (disclosing the general nature of a character) and phonetic compounds (responsible for its sound, and often further narrowing the meaning of given character). Usually, semasio-phonetic characters have a semantically corresponding version in the form of another character of a more complex nature (so called 正字, せいじ, seiji, i.e. correct (traditional) character); however, 空 does not have such a form.

The phonetic part of the kanji 空 is 工 (こう, kō; today’s meaning of this character is “construction worker”, also “craft”, “artisan”, “skill”, etc.).

In 空, 工 also represents a gently curved shape, similarly to the way it does in the character 虹 (にじ, niji, i.e. “rainbow”). The meaning of 工 in the character 空 is (most likely) related to the dome-shaped curvature of the distant horizon, which is a consequence of the Earth being round. In summary, 工 plays the double role of phonetic and semantic components of the character 空. In later stages the original meaning of 空 was expanded from a dome-shaped space to “emptiness” in general.

The semantic element 穴 (穴, ana, i.e. “hole”, “deficit”, also “vacancy”, etc.) suggests “emptiness”, or “lack of presence”, etc. In the book 說文解字 (shūo wén jiě zì, i.e. “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters”) we read that 空 originally had the same meaning as 竅 (きょう, kyō, i.e. “hole”; also “opening” in Chinese). Further, in the commentaries to the above mentioned book, written by the Chinese philologist 段玉裁 (Duàn Yùcái, 1735 – 1815), we read about the “emptiness between the heavens and earth”, i.e. “sky”, “atmosphere”.

4. Selected historical forms of 空.

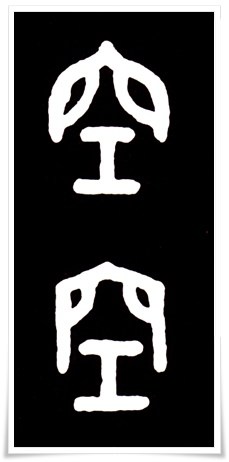

Figure 1. Ink rubbing of the oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun) form of 空, from ca.1600 B.C. – 1200 B.C.

Figure 2. Seal script (篆書, てんしょ, tensho) forms of the character 空, from works of the famous scholar and researcher of seal script, 呉大澂 (Wú Dàchéng, 1835 – 1902); Qing dynasty (清朝, 1644- 1912).

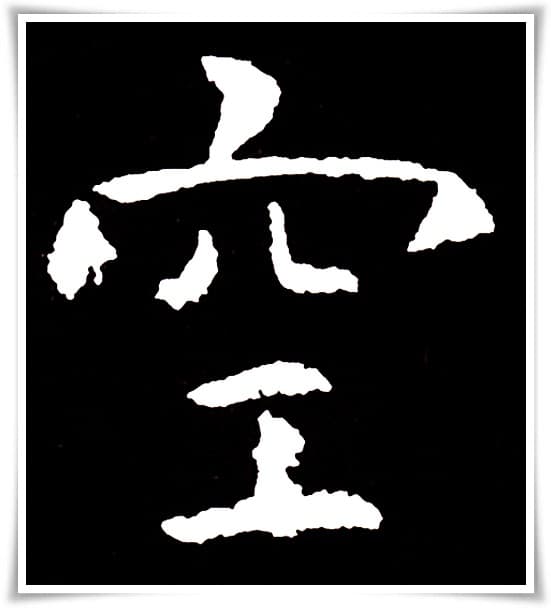

Figure 3. Ink rubbing of the representative clerical script form (隷書, れいしょ) of the character 空, taken from the late Han dynasty (後漢, 25 – 220 C.E.) stele 史晨碑 (Chinese: Shǐchén bēi), dated 169 C.E.

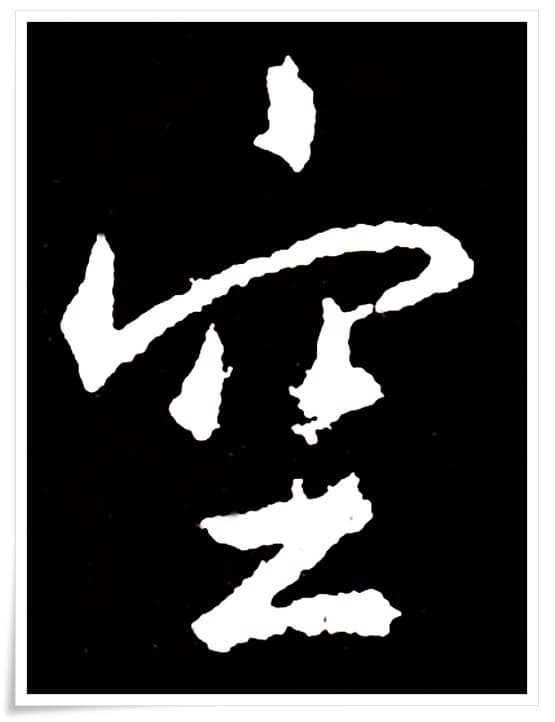

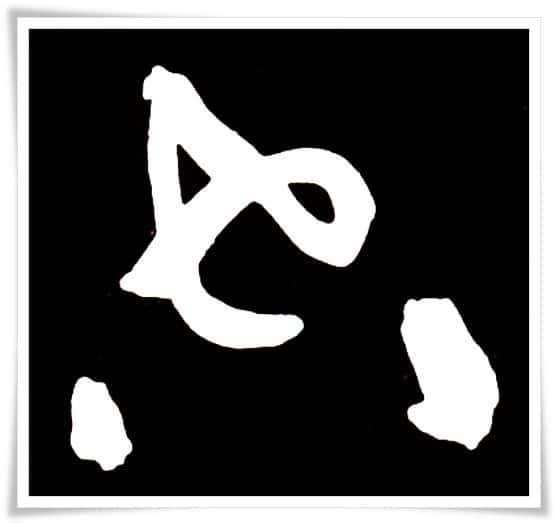

Figure 4. Ink rubbing of a rather advanced form of the cursive script (草書, そしょ) of the character 空, found in the Ming dynasty (明朝, 1368 – 1644) calligraphy by 祝允明 (Zhù Yǔnmíng, 1460 – 1526).

Figure 5. Ink rubbing of the relaxed and supple standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) form of the character 空, taken from the Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907 C.E.) stele entitled 孔穎達碑 (Chinese: Kǒng Yǐngdá bēi), named after its author, the scholar and calligrapher 孔穎達 (Kǒng Yǐngdá , 574 – 648 C.E.), who was a descendant (32nd generation) of Confucius (孔子, Kǒng zǐ, 551 – 479 B.C.).

Figure 6. Semi-cursive script (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) form of the character 空. Ink rubbing from the calligraphy work compilation entitled 集王聖教序 (Chinese: Jí Wáng shèng jiào xù), created on the order of the Emperor 唐太宗 (Chinese: Táng Tài zōng), of the Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907). Characters for this work were chosen from masterpieces of 王羲之 (Wáng Xīzhī, 303 – 361), often referred to as the Sage of Calligraphy (書聖; Chinese: shū shèng), who lived in Jin Dynasty (晉朝, 265 – 420 C.E.).