At times I am asked to submit works for calligraphy exhibitions in Japan. There are various events that take place here and there, and some of them are more interesting than others. In this article I would like to show you what the preparations for such an event look like.

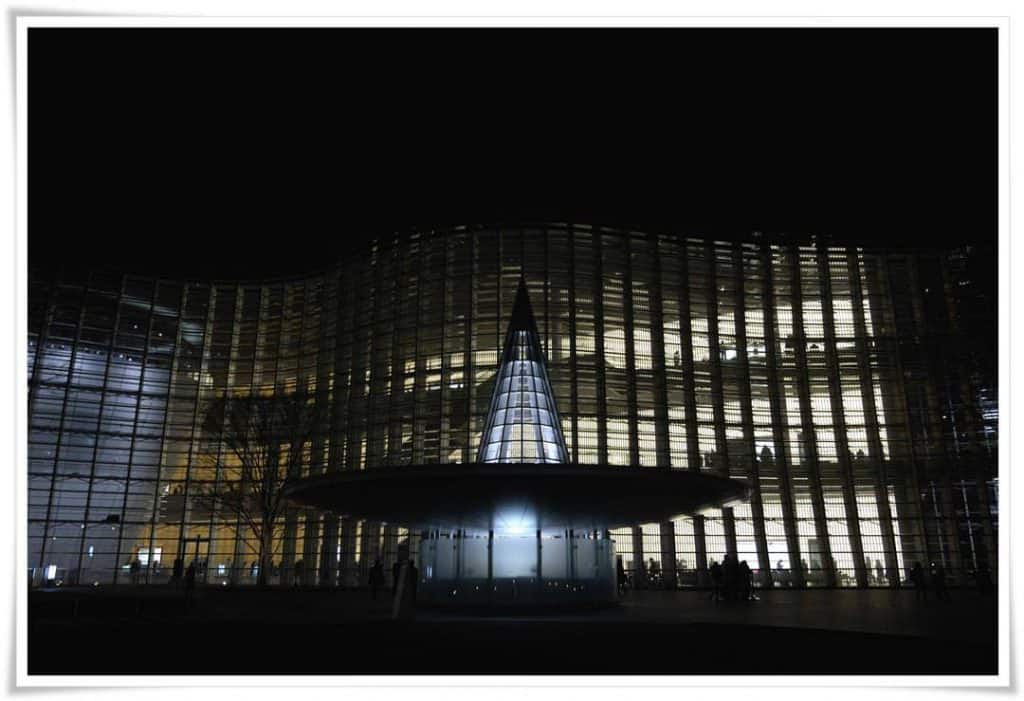

This year’s major exhibition is the 40th Anniversary Exhibition of the All Japan Calligraphy and Literature Association (40 回記念全書芸展, よんじゅっかいきねんぜんしょげいてん, yonjukkai kinen zenshogeiten), to which I belong, that will take place in The National Art Centre in Tokyo (国立新美術館, こくりつしんびじゅつかん, kokuritsu shin bijutsukan), between the 7th and 19th of December. During last year’s event, there were some 3000 works displayed by various Japanese calligraphers, who are related to 全書芸展. At that time, many great modern masters of calligraphy art presented their works. This year will not be any different, so if you are located near the Tokyo Metropolitan area, and fancy a slice of real oriental culture, this is definitely the event of the year. Last year, our calligraphy exhibition shared the building with two or three other smaller calligraphy events organised by separate Japanese calligraphy associations, and an exhibit of original works by Van Gogh. This December, at least four other calligraphy groups will be displaying their art, so the variety of styles and abundance of works will be something to behold

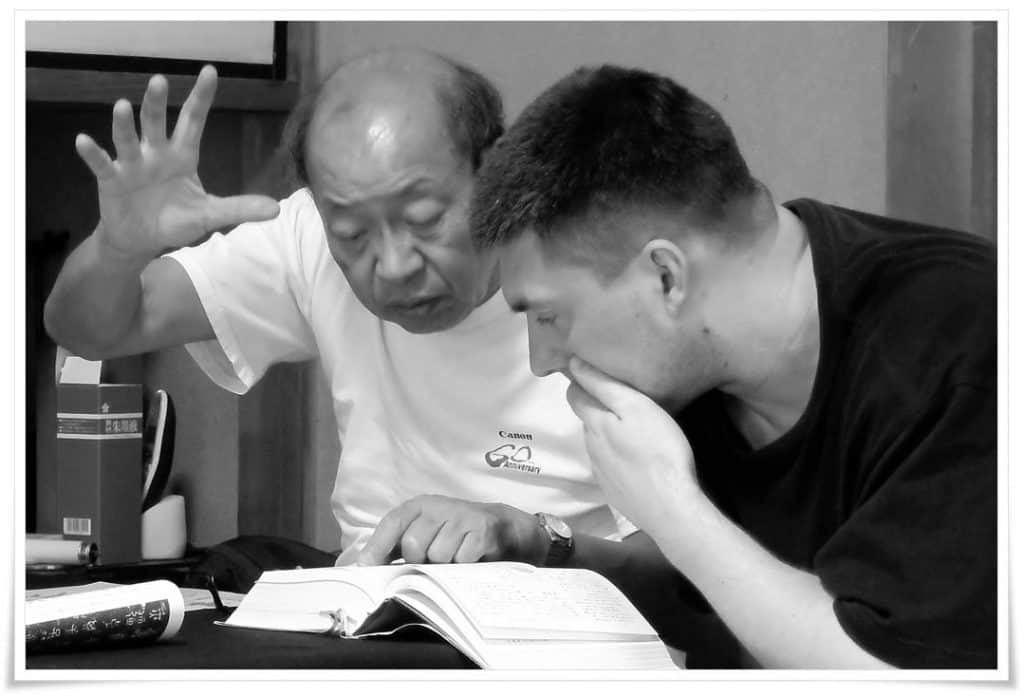

During any exhibition, one can see ready-framed art, but only a few people know how much work it takes to write one calligraphy work that is worth displaying. After discussing the subject thoroughly with my calligraphy teacher, we have decided that this time I should try to complete two types of works. One of them should be 創作 (そうさく, sōsaku, i.e. “one’s own composition”) and the other one 臨書 (りんしょ, rinsho, i.e. “copying masterpieces”), and more precisely 写経 しゃきょう, shakyō, i.e. “Buddhist sutra copying”).

Rinsho is the traditional way of studying calligraphy, a route followed by all of the greatest ancient masters of this art. There are many meanings of this word, as well as many different ways of “copying” in calligraphy, but this is a subject for a separate article. Nonetheless, “copying” does not mean a “forging” or “duplication” of the original masterpiece by repeating all strokes exactly as they were written hundreds or thousands of years ago. The term “rinsho” stands for a skilled way of rewriting a given text while preserving the vigour, the energy flow, and the most characteristic details of the style of the given calligraphy masterpiece. At the same time, while copying, a calligrapher merges all of these elements with his own style. Rinsho is a meticulous work, yet I find it absolutely fascinating and very relaxing. Since calligraphy is considered to be a mirror of the human soul, to study the masterpieces means to study the people who wrote them, their emotional states, and personality at the time of writing. It’s travelling in time, deep inside someone else’s mind.

Rinsho is by far the best tool for strengthening one’s brush technique. Those who do not study ancient manuscripts will never advance in calligraphy, and their works will seem lifeless. Therefore, their own composition will be bleached of any spirituality and depth. It takes years and years of practice to empower the black lines and set them on fire, and to hypnotise the viewer’s heart through the black and white magic of your own handwriting. Calligraphy skill grows with study, but it also grows with the passage of years. Life experiences enchant the mind of the calligrapher, which flows into the brush during writing. It is our memories, knowledge and feelings that we write with, not the arm, or even the brush.

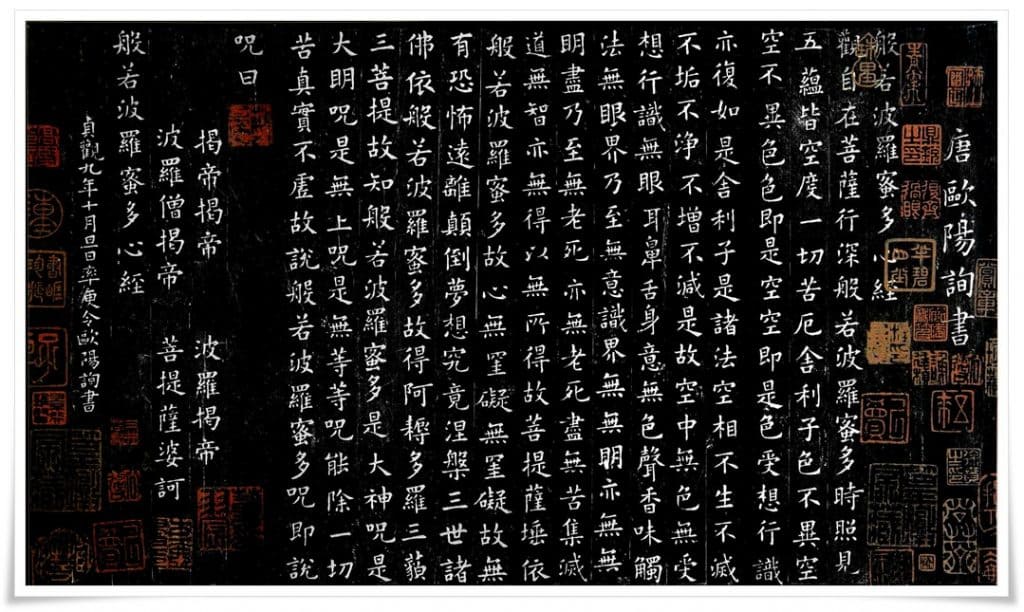

This year I took up the challenge of writing the Buddhist Heart Sutra (般若波羅蜜多心經, Chinese: Bō rě bō luó mì duō xīn jīng). It was composed approximately 2000 years ago, somewhere in the territories of the Kushan Empire (ancient Bactria). It teaches us about freeing one’s mind from all that is irrelevant and cocooning it in the bliss of nothingness. It is one of few sutras not directly referring to the Buddha. Its text is also relatively short (260 characters). The Heart Sutra chanted by the Buddhist monks has an amazing effect on a person’s mind, even if one does not comprehend its meaning. When I lived in central Tokyo, I often visited a local Buddhist shrine, only to listen to it.

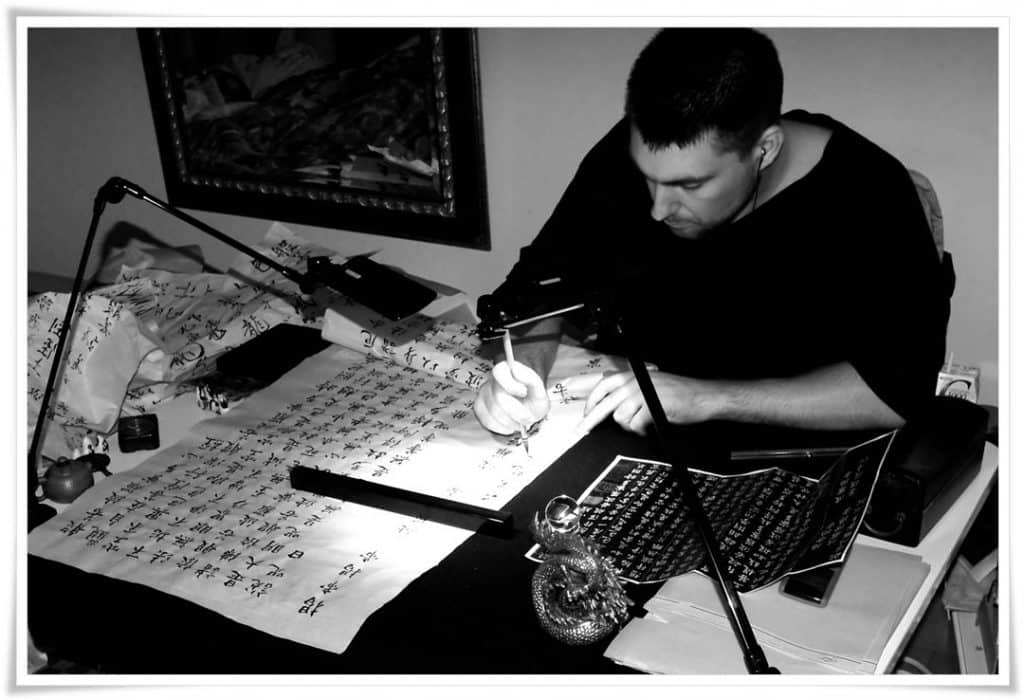

My teacher suggested I try my strength and write The Heart Sutra on a large paper, 52.5 x 135 cm. However, before I started to write on such a large sheet using a small brush, I began my studies on a training paper called in Japanese 半紙 (はんし, hanshi; dimensions: 24 x 33cm) with a larger brush. Rinsho should always be practiced in larger scale characters, in order to catch all the most important characteristic features of a given masterpiece. The text I chose for copying was the Heart Sutra written by the great Tang dynasty master of the standard script (楷書, かいしょ kaisho), 歐陽詢 (Chinese: Ōuyáng Xún, 557 – 641), although some scholars still debate if this particular calligraphy was in fact written by him or someone else. I wrote the sutra text approximately ten times with a large brush, then discussed the details with my teacher whose guidance is always invaluable. Then I started to write on a large paper with a small brush specially designed for copying sutras. Such a brush has a very pointy tip and its tuft resembles a bottle neck shape. I repeated the whole text a few times on the large paper, and I am meeting my teacher again to listen to his final remarks. Each copy of the sutra takes approximately four hours of continuous writing. It is crucial to keep writing and lose oneself in the process, as any breaks or intervals will be obviously detectable in the brush strokes, as a change of rhythm and ambience. So far, I have spent about two months studying the Heart Sutra, and I can only hope to be ready to produce it with confidence.

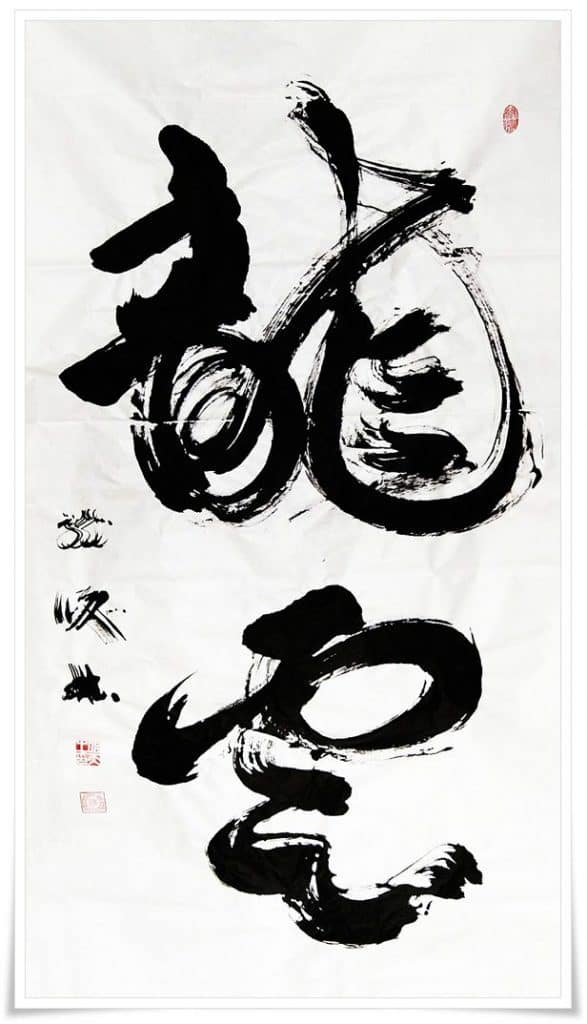

Another work I will submit for selection for the exhibition is my own composition. I have not decided on the text yet, but it will be either 飛龍 (ひりゅう, hiryū, i.e. “flying dragon”) or 龍雲, りゅううん, ryūun,, i.e. “dragon in clouds”). In the Figure 5 you can see me writing with a bundle of three brushes: one big brush made of horse hair, and two sheep wool brushes of various hairs lengths. This is to enhance the lines and spawn more dramatic strokes that will emphasise the mythical nature of dragons, and their symbolic meaning here in the Far East.

Sōsaku is as fascinating as it is tiring, and especially so for large scale works. The paper shown in Figure 5 is 90 x 180cm in size, and it takes some acrobatic skills at times to be able to write on it, as it entails holding a bowl with ink in your left hand while writing with the right, bent over for hours. One needs to coordinate the body and mind and still move with enough freedom to express feelings with a brush. Preparation for writing large scale works is time consuming too. I never use ready-made ink (墨汁, ぼくじゅう, bokujū, “liquid ink”). It is chemical-based and goes against the whole concept and ideology of calligraphy. To prepare the ink for writing on ten to fifteen sheets of paper, I need to spend approximately twelve hours grinding it. It needs to be the right density and colour to convey the precise emotional intensity of the phrase. Lastly, after writing, the brushes must be thoroughly washed to remove any ink remaining in them, and with such large brushes, it takes more than an hour to rinse them clean.

It is true that some calligraphy is created in seconds. The brush touches the paper and it flies away, leaving black traces of our soul on its surface. However, to be able to deliver such powerful writing, it takes long years of diligent study and hundreds of thousands sheets of paper. So, when you see an oriental calligrapher at work, please bear in mind that regardless of how easy it may seem to write with a brush on paper, if his or her 書 (しょ, sho, i.e. “calligraphy”; lit. “writing”) is powerful, it means that it’s became their way of life and there is nothing else in the world that occupies their minds.