1. Meaning:

air, atmosphere, mood, mind, spirit, vital energy, etc.

2. Readings:

Kunyomi (訓読み): いき

Onyomi (音読み): キ、 ケ

Japanese names: does not appear in Japanese names

Chinese reading: qì

3. Etymology

気 belongs to the 形声文字 (けいせいもじ, keiseimoji, i.e. phono-semantic compound characters). This is by far the largest group of Chinese characters, encompassing about 85 – 90% of all kanji, which are constructed of semantic (disclosing the general nature of a character) and phonetic compounds (responsible for its sound, and often further narrowing the meaning of given character). Usually, semasio-phonetic characters have a semantically corresponding version in the form of another character of a more complex nature (so called 正字, せいじ, seiji, i.e. “correct” (traditional) characters). 気 is no exception here, and its 正字 is 氣.

There are more forms of 気 (so called 異体字, いたいじ, itaiji, i.e. “kanji variants”) found in classic literature (at least five of them), and the most complex one is 餼 (き, ki, its current meaning has been narrowed to: “portion of grain”, also, “offering”). 餼 is a an example of traditional kanji made complex on purpose (to precisely define the meaning as “grain ration”, or “offering (food)”), and it is composed of two stand-alone characters: 食 (しょく, shoku, “meal”, “food”, etc.) and 氣. 餼 appeared chronologically later than 氣

The phonetic compound (and not a purely semantic one as many sources suggest) of 気 is 气 (き, ki, i.e. “spirit”, also, “steam radical”). Originally 気 was written as 氣. Before that, certain meanings of 氣 were closely related to (and derived from) the ones of the character 气 (see Figures 1 and 2). However, the ancient 气 is not the same character as modern simplified Chinese 气. The former is a pictograph of a breath in the form of vapour, as observed on a cold day, whereas the latter is a simplification of 氣.

In later stages, by adding 米 to 气, the meaning of the character 気 expanded to “offering food” (symbolised by the rice radical) that sustains life, though it was often represented by its complex form of 餼, as we read in 說文解字 (shūo wén jiě zì, i.e. “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters”) from the 2nd century C.E., compiled by a philologist of the Han dynasty (漢朝, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.), 許慎 (Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.). A similar definition is found in the book on the history of the Spring and Autumn Period (春秋时期, 771 – 403 B.C.E.), entitled 春秋左氏傳 (Chinese: Chūn qiū Zuŏ shì zhuàn), dated (possibly) 389 B.C. This implies that 餼 was already in use interchangeably with 氣, from approximately 700 B.C.

One must remember that rice was, and still is, the staple food in Asia. Ancient China was not any different. 气, though acting mainly phonetically (き, ki), could also be associated with the steam rising from freshly cooked rice (whose meaning was derived from a “breath”, based on the visual association of a person’s “breath on a cold day” with the “steam rising from cooked rice”; see Figure 1 and 2), and therefore to “the spirit of life” in general. Rice sustains life, and life cannot exist without air (breath), hence 气 + 米. This lead to the general use of the kanji 気 as “spirit”, “mind”, “nature (of things)”, “vital energy”, etc., as some theories suggest.

However, today’s 気 has many meanings. It is important to realise that the original meaning (and sound) of the kanji 気, in phrases such as 雲気 (うんき, unki, “look of the sky”, “movement of clouds”) 天気 (てんき, tenki, i.e. “weather”), 風気 (ふうき, fūki, i.e. “lowing wind”), or 気力 (きりょく, kiryoku, i.e. “willpower”), etc., was derived from the phonetic compound 气 (“spirit”). By adding the semantic compound 米 (こめ, kome, i.e. “rice”) the meaning changes somewhat towards 餼 (“offering” (of rice/food), “gift”; the meaning made more specific than its predecessor 氣).

Lastly, the complexity of the multiple meanings of the character 氣 is further emphasised through various calligraphy dictionaries. Some of them list 氣 under the radical 气, whereas others under 米.

4. Selected historical forms of 気.

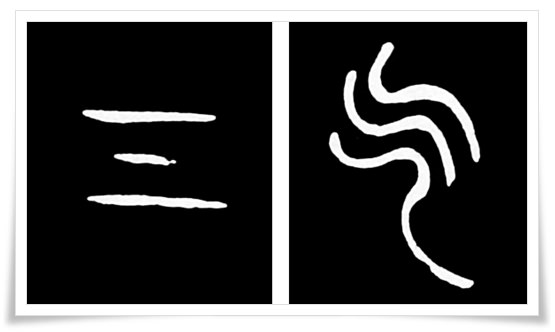

Figure 1. Ink rubbings of the oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun)forms of the character 气. 氣 either does not have an oracle bone form, or it has not been deciphered yet.

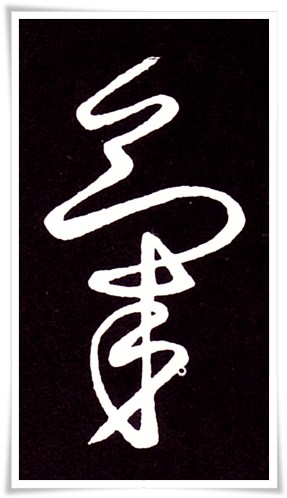

Figure 2. Great Seal script (大篆, だいてん, daiten)form of the character 氣. You can clearly see the radicals 气 and 米. Ink rubbing of the calligraphy written by the seal script scholar and calligrapher 呉大澂 (Wú Dàchéng, 1835 – 1902 C.E.), of the late Qing dynasty (清朝, 1644 – 1912 C.E.).

Figure 3. Ink rubbing of the clerical script (隷書, れいしょ, reisho) form of the character 氣, found in calligraphy work by 伊秉綬 (Yī Bǐngshòu, 1754 – 1815 C.E.) of the of the Qing dynasty (清朝, 1644 – 1912 C.E.).

Figure 4. Virtuous cursive form of the character 氣, attributed to 王羲之 (Wáng Xīzhī,, 303 – 361 C.E.) of the Jin Dynasty (晉朝, 265 – 420 C.E.), who is often referred to as the Sage of Calligraphy (書聖; Chinese: shū shèng),.

Figure 5. Ink rubbing of one of the variations of the standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) forms of the character 氣, taken of the Jiucheng Palace stele (九成宫碑, Chinese: Jiǔ chéng gong bēi), Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907 C.E.).

Figure 6. Ink rubbings of the semi-cursive script (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) form of the character 氣, found in possibly the most cherished calligraphy work of all time, entitled 蘭亭集序 (Chinese: Lántíngjí Xù, i.e. “Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion”), attributed to 王羲之 (Wáng Xīzhī, 303 – 361 C.E.) of the Jin Dynasty (晉朝, 265 – 420 C.E.), who is often referred to as the Sage of Calligraphy (書聖; Chinese: shū shèng). 蘭亭集序 was composed in 353 C.E.

5. Useful phrases

- 天気 (てんき, tenki) – weather

- 気分 (きぶん, kibun) – mood, feeling

- 雰囲気 (ふんいき, funiki) – atmosphere (as in “mood”), ambience

- 気味 (きみ, kimi) – sensation, feeling

- 病気 (びょうき, byōki) – illness, sickness