Echoes of the ancient world.

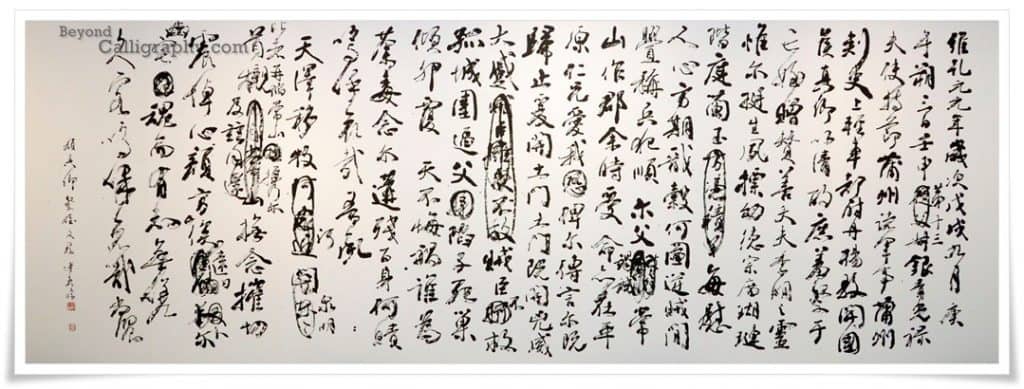

There are many calligraphers out there that throw themselves into the unknown and dangerous waters of 創作 (そうさく, sōsaku, i.e. “own composition”), without building a solid foundation through years and years of study 臨書 (りんしょ, i.e. “copying masterpieces”). In effect, their works are weak, pale and lifeless. The 臨書 of Master Ishitobi Hakkō shows how much knowledge he possesses and how powerful his brush technique is. The work pictured in Figure 11a stands out in particular, but also the ones shown in Figures 14 and 15 clearly manifest his true mastery of the art of calligraphy.

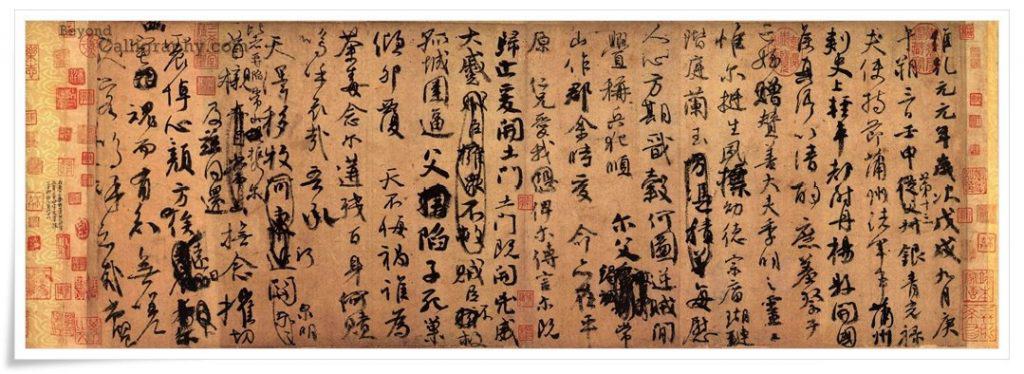

Figure 11a is a 臨書 of the extremely emotional calligraphy by the outstanding calligrapher of the Tang dyansty (唐朝, 618 – 907) 顏真卿 (Yán Zhēnqīng, 709–785), entitled 祭姪文稿 (Chinese: Zhài zhí wéng gǎo, i.e. “Lament for nephew Zhai). Lament for Nephew Zhai (Figure 11b) sends electricity all over my body every time I gaze upon it. Covered in corrections, emotional accents, rapid brushworks, racing across the paper like wild dragons through storm clouds, sudden pace changes achieved by the masterful blend of the thick and slow strokes with the curved and wavy ones, as if master Yán was unable to see what he wrote through tears in his eyes. This masterpiece is considered the second most treasured calligraphy ever written in cursive script (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho). Once again, while admiring his work, it is understood without a shadow of doubt that emotions are the core of Far Eastern calligraphy. Without them, the ink smudges cannot live on, and the paper, cannot nourish their existence

Master Ishitobi Hakkō did not simply copy this masterpiece. He enhanced it with his own interpretation. It is not the exact copying skills that show the true mastery of calligraphy, but the understanding of the energy and mind-set of whoever wrote the given piece, and then the ability of putting it on the paper.

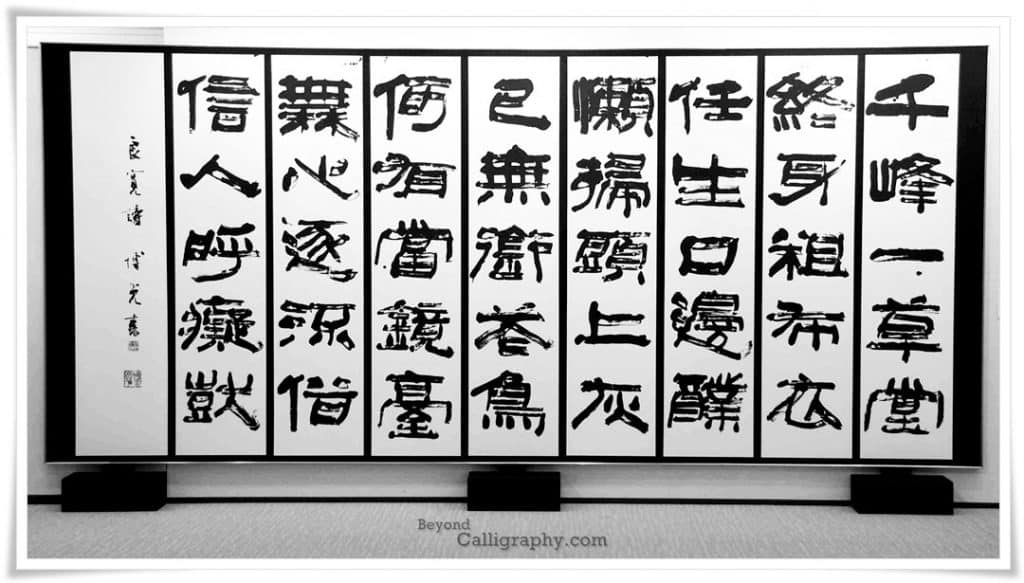

Figure 12 is a calligraphy of a poem by Ryōkan Taigu (良寛大愚, りょうかん たいぐ, 1758–1831), an eccentric Zen Buddhist monk and a hermit of the Edo period (江戸時代, 1603 – 1868). This text is written only in kanji, in bold and powerful clerical script (隷書, れいしょ, reisho). Nonetheless, despite the heavy looking characters, the brush strokes abundant in kasure (掠れ, かすれ, i.e. “streaks of white”) make the thick lines look lighter and more agile, giving the whole work an airy, sort of transparent, feeling. It fits very well with the nature of the poem. The text starts with a beautiful phrase 千峰一草堂 (せんぽういちそうどう, senpō ichi sōdō), which translates into “Thousand mountain peaks, one humble abode” – a reference to a true Zen monk’s dwelling, surrounded by nature and free of any disturbances of the modern world.

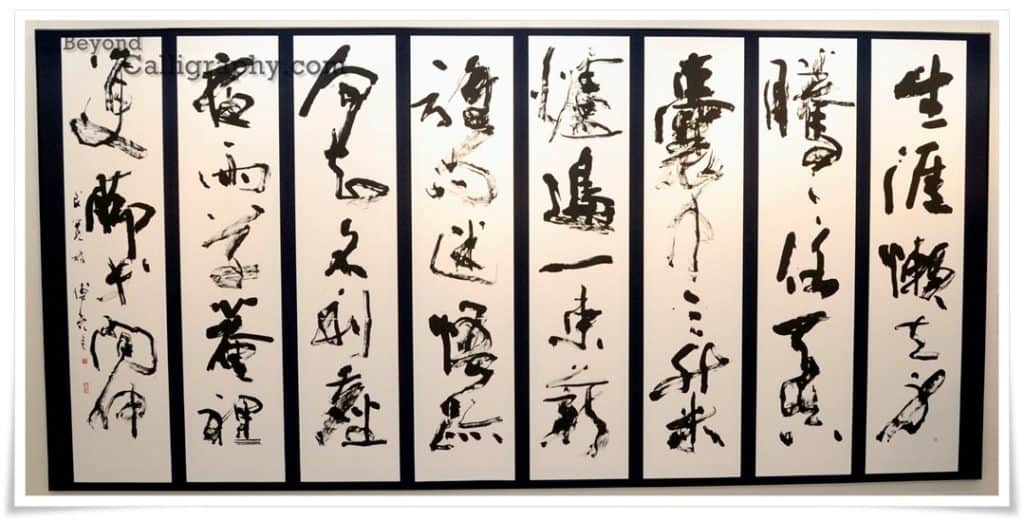

In Figure 13 you can see a calligraphy in cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) of another poem by the afore-mentioned Ryōkan Taigu, entitled 生涯瀬立身 (しょうがいせりっしん, shōgaise risshin), which means “success is not what I care about in life”.

I chose those two works purposely to show you how pure the heart of an oriental calligrapher must be, in order to create a true masterpiece. How void his mind is and how non-existent his desires are. Taoism teaches us that all form emerges from nothingness, and to nothingness it always returns. To understand the abyssal depth of calligraphy, one needs to embrace the complexity of its simplicity. And this is accomplished only by means of two colors. I wrote once that calligraphy is created in absence of pride and glory, and it is as simple as that humble hut hidden away from the mortal commotion within the thousand mountains of nothingness.

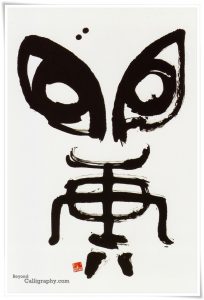

Works 14 and 15 are 臨書 interpretations of early 金文 (きんぶん, kinbun, i.e. “text on metal”) script, c.a. 1600 – 1500 B.C. If you care to read more about this fascinating script, please click here. Figure 14 is a calligraphy of a kanji (Japanese reading: か, ka) that semantically corresponds with the character 爵 (Chinese: jué). It is an ancient wine holder with three legs and a loop handle, usually used by kings as a ritual vessel. Unfortunately, I am unable to type in the original character, as the Japanese language input system that I am currently using does not list that kanji.

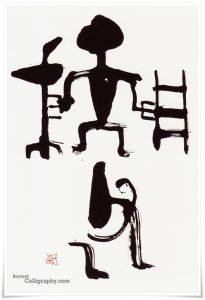

Figure 15 is 臨書 of a two character phrase 父乙 (Chinese: fù yǐ, i.e. “in the name of Father”). It was cast on a bronze tripod and offered as a gift. One needs to bear in mind that during early Shang dynasty (商朝, 1600 – 1046 B.C.), bronze was the most precious metal.

There were a few more works in kinbun script displayed during the event, and their ancient raw appearance contributed to the specific ambience of the exhibition. Naturally, it is impossible to list all of the works here, and it is a shame as every single one of them was unique and outstanding. I am definitely looking forward to next year’s exhibition of this great master.