Chiune Sugihara was a Japanese diplomat who, in July of 1940, through extraordinary measures and under seemingly impossible circumstances, selflessly saved the lives of endangered Jews. To honor his memory and that of those whose lives were both lost and saved, artwork by Rona Conti can now be viewed at the Sugihara Foundation and Museum in Kaunas, Lithuania.

In the late 1930’s , as World War II approached and Jews were being rounded up, a man named Joseph Shimkin from Poland but living in Vilnius began to realize that he would be trapped along with thousands of others. He went from embassy to embassy seeking an exit visa to no avail. The United States, Britain and Australia all said that they could not help.

In desperation, even though it seemed impossible, he and other Jews approached Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese diplomat to Lithuania. The Diplomat himself acknowledged the difficulty but said that he would inquire of his government. The response was a resounding no. Asked what would happen if they did not get a visa, the answer was that the Jews would not survive.

Under these circumstances, Sugihara undertook the writing of transit visas as a humanitarian at what was to become great personal cost. He was recalled from his post a few weeks later, then transferred from post to post until his diplomatic ties were severed once he and his family returned to Japan in 1947 after having spent 18 months in a Soviet Labor Camp.

While the deeds of Sugihara later became known and his designation among the honored occurred during his lifetime in many countries, in Japan his life was one of great hardship and difficulty to support his family. What he did was not considered heroic but rather shameful, and his story was not publicized.

Joseph Shimkin was the last of the Sugihara “survivors” who had received an exit visa and stayed in Japan for the rest of his life. Others emigrated around the world. It seems fitting that shortly after Mr. Shimkin’s passing, The Japanese Ministry of Education decided that the story of Sugihara’s deeds should be taught in the national curriculum, and his designation should be an honorable one and a beautiful lesson for humanity.

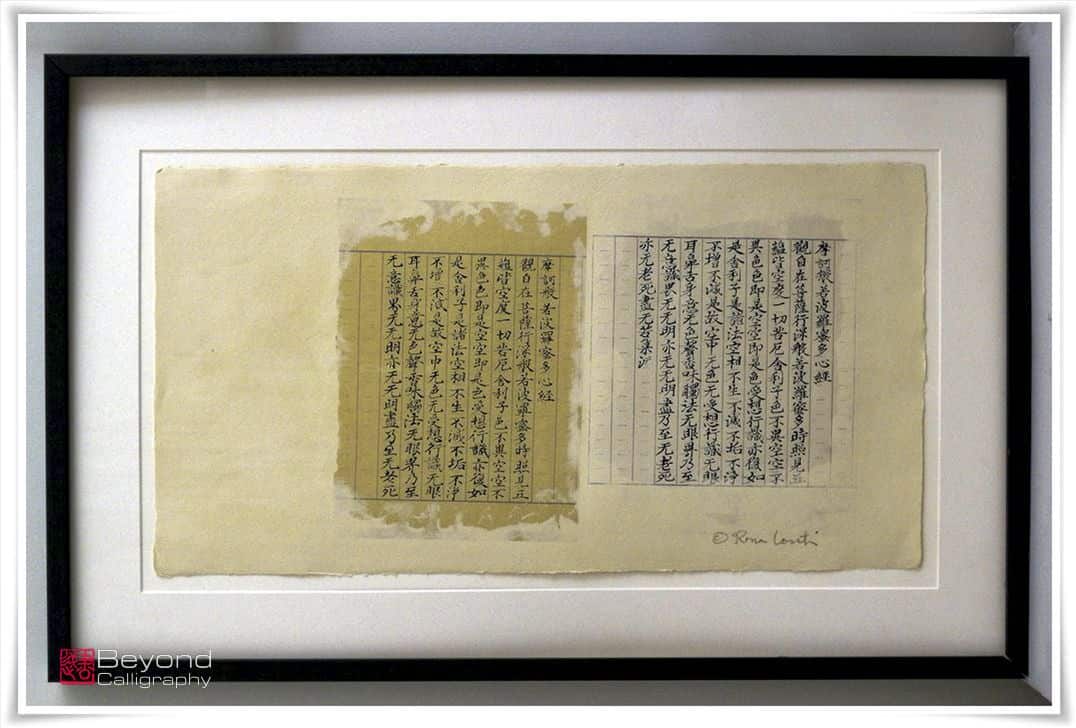

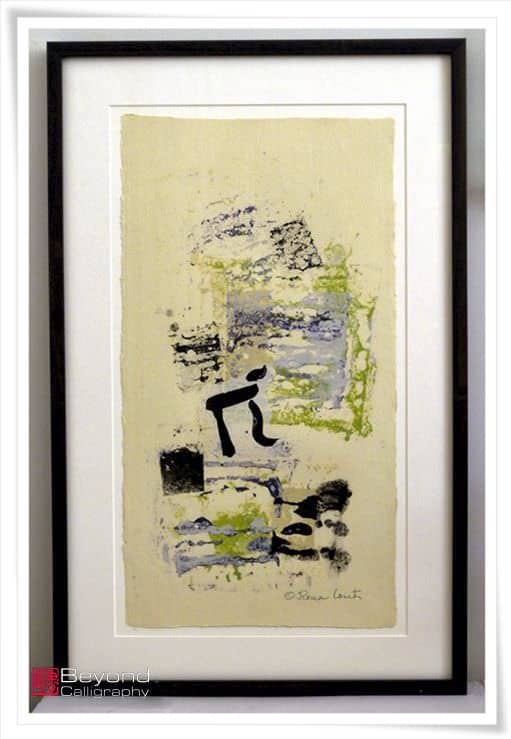

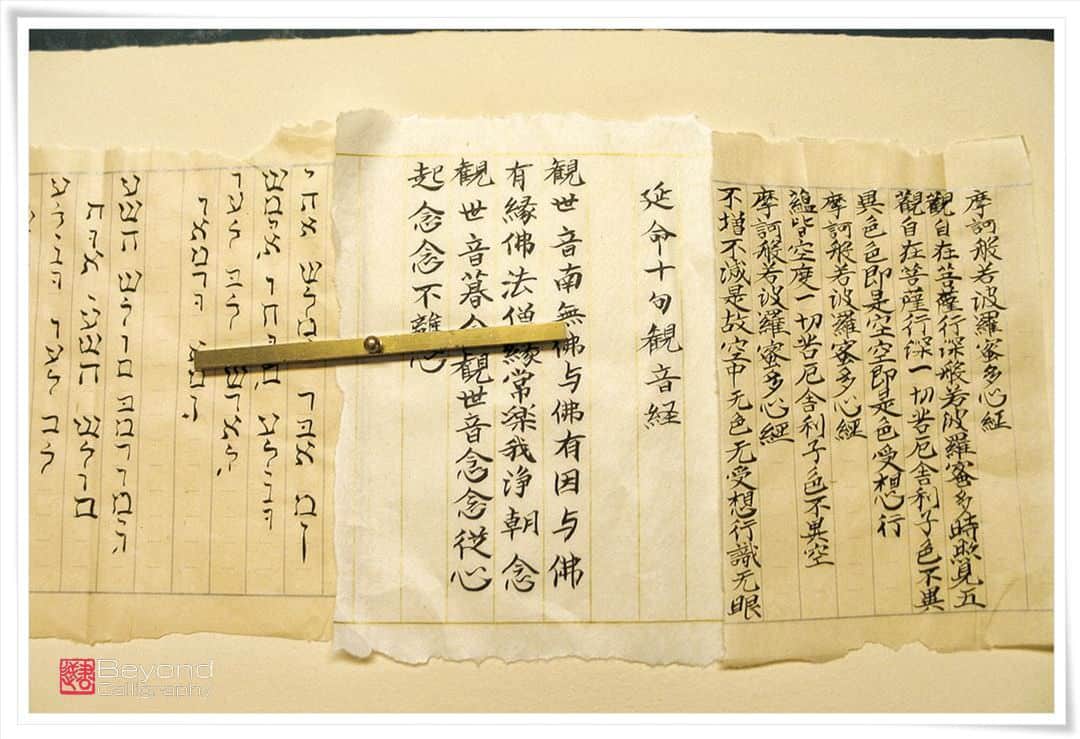

Two pieces were created to honor Sugihara, “Chai” and “Fragments of the Heart Sutra”.

The Heart Sutra is the most well-known and beloved sutra/prayer in Japan, beautiful, concise, and profound. Called the Hannya Shingyo, it is chanted in temples by priests and monks and lay people and is hand copied regularly by Japanese and devotees. It is easy to memorize because of its concise length, less than 300 syllables, and it captures the essence of Buddhist teaching. In copying or chanting the Heart Sutra, it is believed that one can absorb and manifest its wisdom.

The artwork titled “Fragments of the Heart Sutra” consists of two sections of the beginning of the Heart Sutra, both unfinished, and arranged with a larger empty space as the third component of the whole. The purposeful selection of two fragments and a blank space was chosen to represent the spirit of Chiune Sugihara. His devotion and dedication to saving lives continued until he could no longer write. His “Conspiracy of Kindness” story may be found here. “Chai” is a symbol and word that figures prominently in Jewish culture and consists of two letters of the Hebrew alphabet, Chet (ח), and Yod (י). In Hebrew, “chai” means “living” and is (חי), related to the term for “life,” chaim, as used in the expression “am yisrael chai!”, “The people of Israel live!”

Chai, amidst an abstract background, has been depicted backwards or reversed. Sugihara worked tirelessly preparing Visas to save as many Jews as possible. One visa might be for a whole family. Thus, an estimation of the number of lives saved is difficult. In addition to his signature, seals with Japanese characters had to be affixed to the visas. His wife, in tandem with a group of Jews who had beseeched him for help, assisted with stamping the visas. The Jews, unfamiliar with Japanese characters, often placed the seals reversed or upside down.

The artworks “Chai” and “Fragments of the Heart Sutra” were presented to the Sugihara Museum in 2013. Current information about the Sugihara museum and foundation may be found here.

More information about the Sugihara story and his honored designation may be found here.

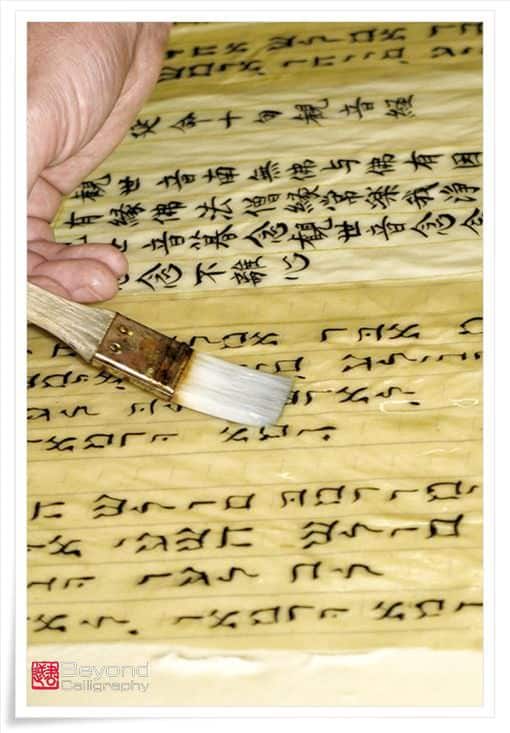

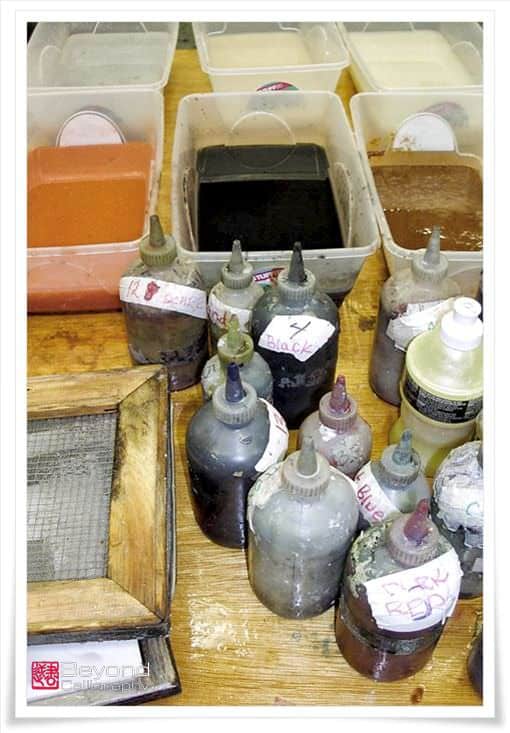

The images of the handmade paper artwork are not paint on paper but are made of paper pulp itself, applied and layered, collage-like in a myriad of ways so that they become all of a piece. The process requires a great deal of equipment and preparation before, during, and after the making of the artwork. An artist wishing to work in this medium, creating what is sometimes called “pulp painting”, must find the relatively rare special studio in which to do this work.

I have attempted to show the pulp painting process through the photographs. The work was produced at and photographs were taken at Dieu Donne in New York City. Dieu Donné is the world’s leading cultural institution dedicated to serving established and emerging artists through the collaborative creation of cutting-edge contemporary art using the process of hand papermaking.

Artwork Commissioned by Ira and Marcia Wagner of Bethesda, Maryland in loving memory of our maternal grandparents Ida Berman Jacobson, born 1892 in Vaskai, Lithuania and Samuel Jacobson, born 1890 in Kovno, Lithuania and died in Baltimore, Maryland Oct. 31st, 1974 and April 9th, 1975.

****Update from Simas Davidovich, Director of the Sugihara Foundation and Museum. “Visas were issued in July-August, 1940 in Kaunas, Lithuania which was then occupied by the Soviet Union.

Soviets were told to close all diplomatic offices as Lithuania lost its statehood. Kaunas was the capital of Lithuania as the ancient capital Vilnius was part of Poland between 1921-1939 .

After “the visa story “, Consul Sugihara worked as a diplomat in Prague , Konigsberg and Bucharest. After that he was imprisoned in a Soviet camp of interned persons outside Odessa and came back to Japan at the end of 1946.

The Foreign Ministry of Japan rejected all deeds of Consul Sugihara as positive ones, and he was fired for giving visas in Kaunas. He was allowed to issue a visa if the refugee had a third country visa and money to stay in japan for two weeks.

But Sugihara was kind enough not to check on availability of money as he understood that most of Polish refugees escaped without documents and money.

Sugihara had a choice- to help or not to help, and he decided to help as a humanitarian. No one directed his act.”