Considering this, you may think that Japanese women in medieval times would have been under a large constraint. But this is quite not true. There is a famous anthology called Hyakunin Isshu which comprised of the 100 best poets from the mid-7th century to the beginning of the 13th century, with one poem from each poet. Poets were considered highly-educated intellectuals in those days. For example, the first poet on the list is the Emperor Tenji who lived from year 626 to 671. In other words, in my opinion, you may consider this anthology as a list of 100 best known intellectuals between the 7th and 13th century. Of the 100 poets, 21 were women. And if you look at mid-10th to mid-11th century, an era where novels and essays such as The Tale of Genji or The Pillow Book were published by aristocratic women, surprisingly 35% of the poets selected in Hyakunin Isshu were women. It is truly ironic to observe this when taking into consideration of the fact that the Japanese government is struggling to make the ratio of women in managerial role hit 30% by 2020.

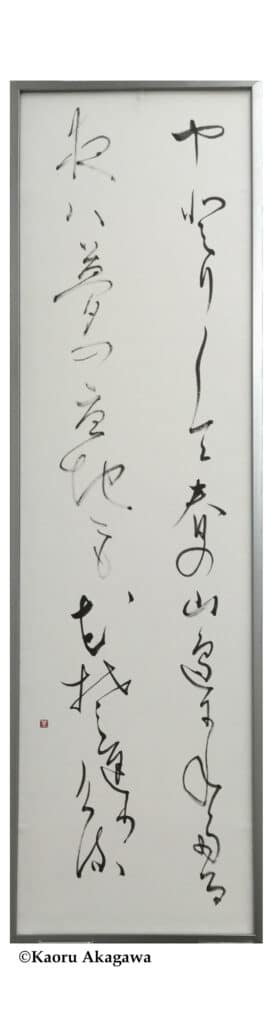

This empowerment of women in the 10th and 11th century was due to the emergence of Kana Shodo. As I have written in my previous article, Kana refers to the ancient Japanese syllabic characters, which were developed before the beginning of 9th century in Japan based on Kanji characters imported from China. Kana Shodo is mainly written with Kana characters, with some Japanicised Kanji characters (和様漢字) being mixed in to support the sentences. The term Kanji literally means “Han Dynasty Characters”, and are called “男手 (Otokode)” literally translated “Man Hand”. For Japanese in the ancient and medieval times, Kanji was a foreign language which was compulsory in order to have a contact with our great neighbouring country, China. This would be similar to Latin in Europe, which was the official language of the Roman Catholic churches. This style of Shodo is called Kanji Shodo. In Kanji Shodo, you only use Kanji characters. Learning Kanji Shodo was necessary for reading Buddhistic Sutras that were written in Chinese and for the exchange of diplomatic documents with China. Kanji Shodo is a male-dominated style of calligraphy, and one that samurais and monks learned diligently in order to get promotions. Today, when you refer to “Japanese calligraphy”, you would normally be referring to this Chinese style calligraphy which is practiced by the Japanese.

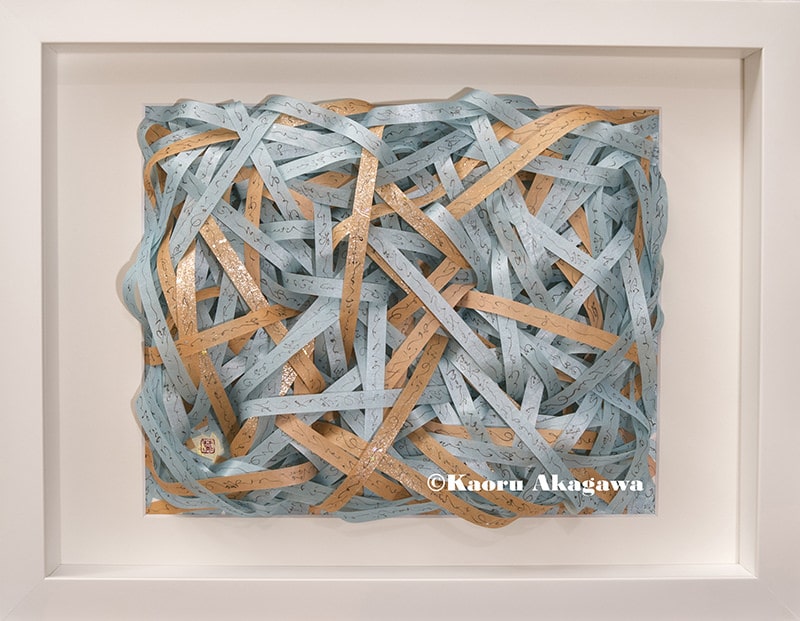

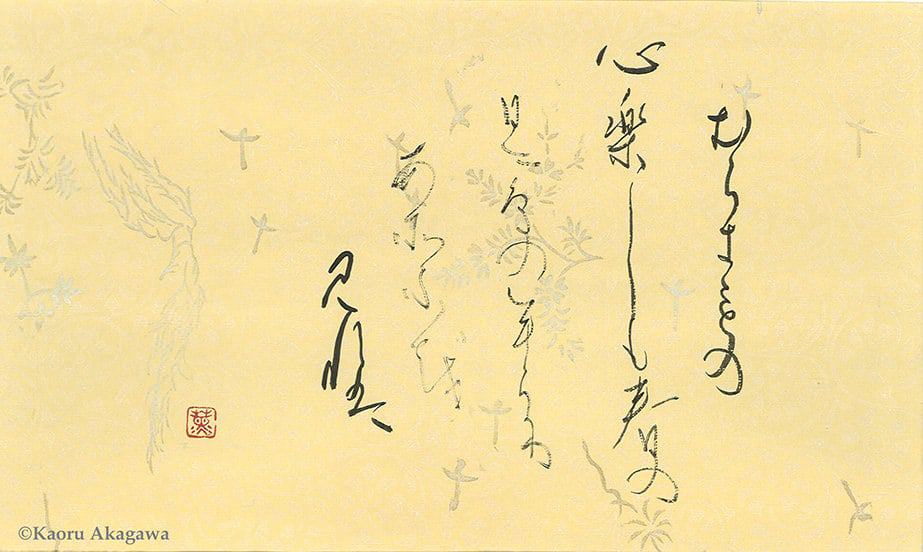

On the contrary, Kana characters are called “女手 (On’nade)” meaning “Woman Hand”. As Kanji Shodo was used by men to work, and because it was a foreign language, it was undesirable for women to learn this. However, due to the emergence of Kana characters, women were also free to learn how to read and write. Once they had come into contact with the joy of expressing themselves through writing, the intellectual women of the nobility started to compete with each other and published significant novels or essays, and this is how the masterpieces such as The Tale of Genji or The Pillow Book were created in the early 11th century. This is truly a worldwide rarity, to see women’s literature flourishing so early in history. As such, Kana Shodo is a female-dominated art, and reached its zenith between the mid-10th to 12th century. It is a style of calligraphy that was disseminated and brought to life by medieval Japanese women, enabling them to express themselves freely in their own language, Japanese.

Tosa Nikki written by Kino Tsurayuki is also a good proof of this empowerment of women in medieval Japan. Ki no Tsurayuki was an aristocrat courtier and the provincial officer of the Tosa province, current Kochi prefecture, and he decided to write a diary novel in the 10th century on his trip back home from Tosa to Kyoto, capital city at that time, on completion of his term of service. Men at that time were expected to write diaries in Kanji Shodo using Chinese language. However, since Ki no Tsurayuki wanted to express his personal feelings free from constraints in his own language Japanese, he chose to write Tosa Nikki in Kana Shodo pretending that he was a woman. The fact that he was not able to write it as a man depicts clearly that publishing personal literature in Kana Shodo was considered inappropriate for men in the 10th century. It is amazing when considering the fact that Charlotte and Emily Bronte had to use male pen names in the 19th century to be taken seriously. It was until the beginning of 20th century that society found it essential for women from the upper class to learn how to read and write Kana Shodo to show that they were highly educated.

Similar to the fourth-wave feminism in the 21st century gaining its steam by social media, the development of Kana characters and the dissemination of Kana Shodo, in other words acquisition of new communicating method, had given the women in the medieval Japan the power to assert themselves. Unfortunately, as I have explained in my past article, most of Kana characters, which supported female authors in medieval Japan, were abandoned in the course of modernization due to technical and educational reasons and only 46 characters survived to the 20th century out of more than at least 550 characters. Currently, the only exceptions where one can see the eliminated Kana characters in Japan are for example, on a sign for a soba restaurant. It is not an exaggeration, when I say that only those who practice Kana Shodo could read and write ancient Kana characters. Furthermore, if you ask your Japanese friends if they are aware of the fact that there used to be hundreds of Kana characters until the year 1900, chances are they probably don’t.

One of the questions I always get at my lectures on Kana Shodo is, how many Kana Shodo calligraphers there are in Japan. This is a very difficult question to answer due to the very ambiguous definition of what a “calligrapher” is. Regarding Shodo in general, there is a survey that there are currently 4 million people in Japan, who use brushes and ink to write, but this figure is including junior high school students who practice Shodo as part of their school education activities. There is also a survey that the number of people who write their texts with brushes is falling roughly 300,000 every year. So, the Shodo population itself is shrinking precipitously. On top of that, there is a survey that currently only 16% of the works exhibited at the Mainichi Shodo exhibition, the largest exhibition of its kind in Japan, are Kana Shodo works. If we formulate a hypothesis based on these surveys that 16% of all 4 million “calligraphers” are practicing Kana Shodo (640,000), and that it is plummeting by 48,000 people (16% of 300,000) every year, then we would have no more Kana Shodo practitioner in 13 years. Of course, this calculation is an exaggeration and we would definitely still have Kana Shodo calligraphers in 2032. At least, I would be practicing it as long as I am fit and alive and can move my right hand in 2032. However, I find it also crucial to point out that the Kana Shodo population is a very aging population and the average age of Kana Shodo practitioners is very high, and there is an unignorable risk that Kana Shodo population may shrink even more drastically than my very rough calculation. For this reason, I find it my obligation to disseminate the story of Kana Shodo and Kana characters to the world and to pass this beautiful tradition of “Woman Hand” on to as many people as possible.