In 1985 I met Kobara Ranseki Sensei, an extraordinary master of Japanese calligraphy, with skill in ink painting as well. He was the founder of the Ranseki Sho Juku system of traditional calligraphic art and the co-founder of the Kokusai Shodo Bunka Koryu Kyokai, an international shodo association headquartered in the Tokyo area.

Kobara Sensei was held in high regard by me and his other students, who all wanted to find the source of his mastery. But it wasn’t just us.

The Japanese community in Northern California, where he lived and taught, revered him. His style was singular and his skill exceptional, leading to awards for excellence in shodo from Japan’s Foreign Minister, Prime Minister, and culminating in his receiving the Order of the Rising Sun from Emperor Akihito.

An exceptionally calm and kind man, he viewed shodo as a Do, or “Way,” to enlightenment through the brush. Refusing to think of his teachings as shuji, mere “handwriting,” he conveyed countless life lessons to me over a period of 20 years of study. But he consistently displayed and referenced one essential quality more than all the other principles he taught: mushin.

The Mind of Mu

The word mushin (無心) is well known in classical Japanese art forms, where it’s defined as “no mind” or “empty mind.” Both definitions are literal and correct, although they may suggest different things to the average person. Just as often, mushin is explained as a mental state that allows for greater effectiveness in the performance of a traditional Japanese art.

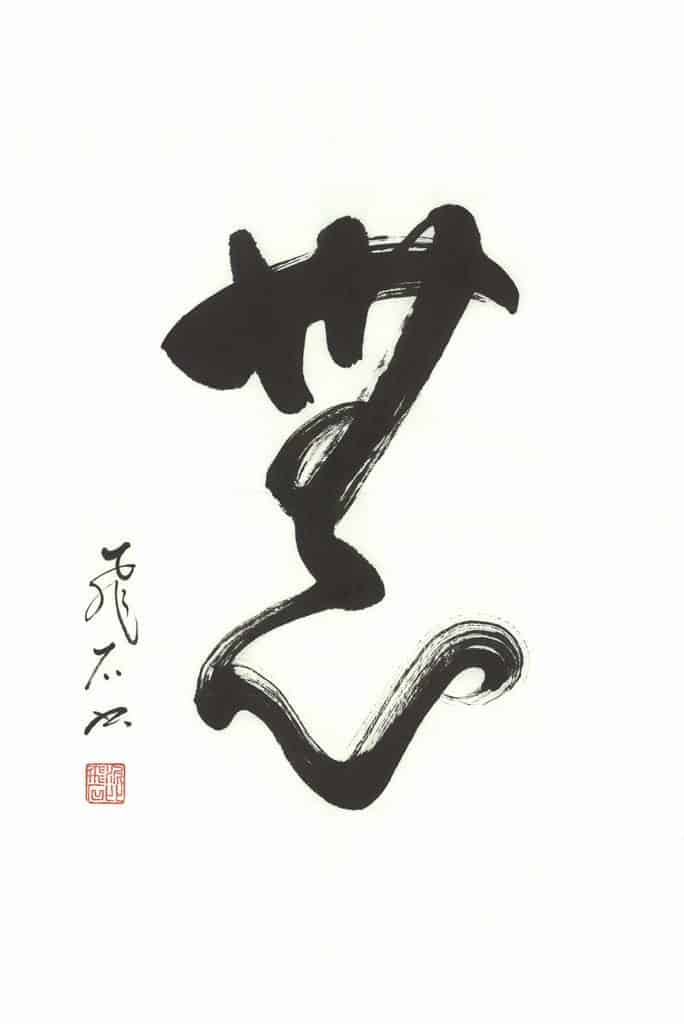

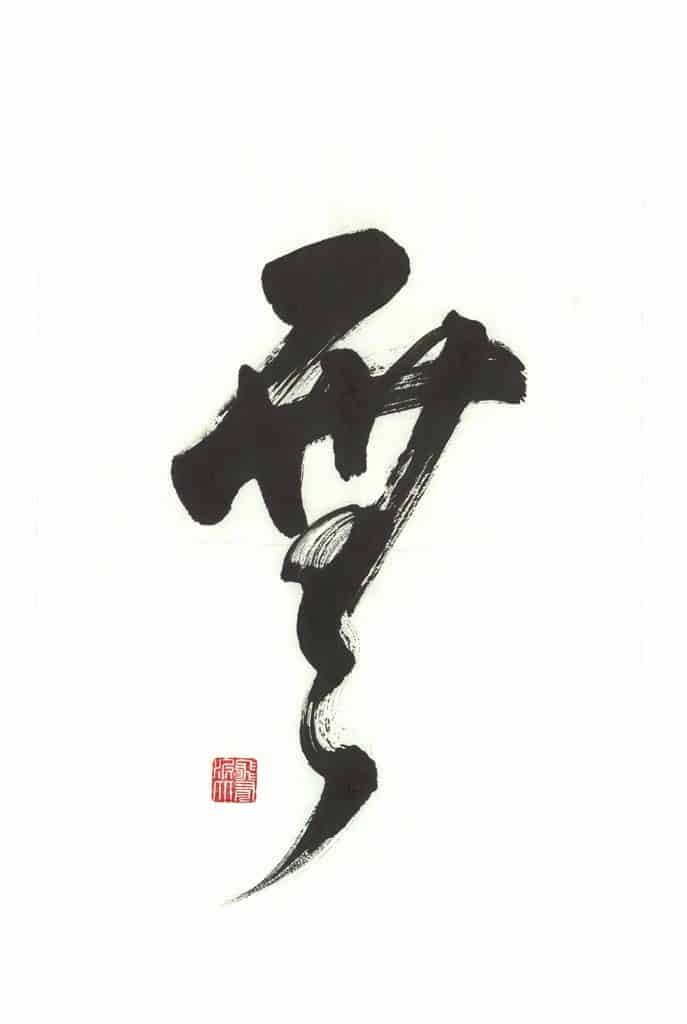

It is mushin that Kobara Sensei almost always reverted to when describing what happened to him when he brushed one of his masterpieces. And it’s mushin that he regularly painted on shikishi at his demonstrations. (A shikishi is stiff, pre-mounted paper about eight by seven inches.) This concept/psychological state, perhaps more than any other, is central to understanding the basis for his art.

But what, more explicitly, is mushin?

Discovering Mushin and Subconscious Reaction

I started martial arts (jujutsu) with my Dad when I was five. At age seven I was enrolled in a judo school, populated by mostly Japanese-American children, who became my friends. My first exposure to the word “mushin” was in association with Japanese and Japanese-American martial arts teachers and their kids.

I spent hours each week with them and their families, at the dojo and in their homes. I grew up around chopsticks and inari sushi, Zatoichi movies and shodo on the walls. And mushin.

I’d heard the word in judo, but it wasn’t taught. Later, I read about it in martial arts books, but it’s not an easy concept to wrap your head around. But I knew even then it was important.

Then one day something peculiar happened. I was a teen training for an important judo tournament: the A.A.U. Junior Olympics. Back then in the U.S. the Amateur Athletic Union sponsored an Olympics for young people in multiple sports. Judo, being an Olympic sport, was one of them, and competition occurred at district and regional levels. I’d won a gold medal in the district competition, representing the judoists in my town, which qualified me to compete in the regional Junior Olympics encompassing a much larger area.

It was my final match against a hard-hitting competitor. We’d been trading throws for a while, neither able to score, when suddenly my opponent was on his back with me over him, poised to crash down and pin him to the ground.

I had no idea what happened, other than I could hear my kiai, a loud guttural shout used in judo, and the referee roaring “Ippon!” I’d won the match by a full point (ippon) and another gold medal.

Not a clue as to how I did it.

But with the match over, details came to me. My favorite technique I drilled hundreds of times daily was o soto gari, “major outer reap.” It involves using your leg to sweep an opponent’s leg out from under him or her, resulting in the person being walloped onto their back. I saw an opening to use it, and my rival was down. But it felt like frames missing from a film. One second we were standing and the next he wasn’t, with no conscious thought and nothing in-between.

How did that happen?! Then I remembered mushin.

Mushin describes a state of mind similar to my tournament experience, a condition in which action occurs naturally, instantaneously, and without conscious forethought. Back then I thought it was specifically a martial arts term. It’s not.

If anything, it might have originated in Zen, shortened from mushin no shin (無心の心)—“a mind without mind, a mind of no mind”—an emblematic Zen conundrum. Despite what’s commonly believed, although Zen had a big influence on some ancient martial arts schools, every samurai didn’t universally feel its impact; many actually favored esoteric Shingon Buddhism. Regardless, even if Zen didn’t inspire all ancient martial arts, it did influence some, along with tea ceremony and other Japanese arts. Today, mushin’s referenced in manifold art forms in Japan, not just martial arts, and just as widely misunderstood. Let’s consider the confusion while we continue looking at what mushin is.

Mu in Mind

To do that, we need to consider and start with the mind. Let’s first look at the nature of the mind and consciousness in general, then we’ll examine what the empty mind is in particular, and finally we’ll determine how it results in effortless and extraordinary shodo art.

So what is the mind? Is it our thoughts? Is it memory? Is there a difference between thought and memory? Are there other aspects to what we think of as “the mind?”

Few consider these questions, which is strange. We all have a mind and mention it regularly. But not many know what we call “mind” is.

Most folks are solely aware of their thoughts, just as most moviegoers only center on the impermanent images flitting across

an empty screen. The screen is hardly considered nor is the existence of anything other than thought. And thoughts are not “ours” in the same way that a bicycle belongs to us. They appear of their own accord and dissolve when we try to hold onto them. They are associated with us, but I’m not sure they are us, nor can we fully control them, unlike a bike that does what we tell it to do.

If you engage in meditation like me, you can watch the movement of thought. If you do it enough, you notice a gap between thoughts. In that space, that pause, do you exist?

The question may seem silly, but we act as if we’re the thoughts passing through the mind. If this is true, then what becomes of us between thoughts? Obviously we still exist; we don’t lose consciousness. Something is there—maybe just for a second—but it’s not thought. Some call it mu (無), “nothingness,” as in mushin: the celebrated mind set embodied by legendary calligraphers, martial artists, and meditators.

But what about memory? It also comes and goes, without being under our full control. We behave as if it’s real, but the event recalled has no current reality. Yet when remembering a scary incident respiration increases, heart rate goes up . . . as if the real thing was happening. But it’s not, except in our thoughts. It’s an illusion that we experience constantly without realizing it.

Thought and memory are mutually dependent. Thoughts we form are rooted in memories of the past that we believe might have some connection to the present. That’s why if several people see the same thing, they have different thoughts about it. For identical thoughts to happen simultaneously, we’d have to have a matching past and memories. That doesn’t happen.

And recollections are experienced as thoughts, even thoughts about the unknowable future. Since we don’t know if we’ll be here tomorrow, to think about it we guess using memories that we believe might happen again in a variant form. Since no two people remember an event the same way, it means memory (like thought) isn’t as stable and accurate as we imagine.

Thought and memory cannot be fully separated, both are impermanent, both aren’t completely within our control, and while they’re associated with us, they are not us. If you do nothing and observe your mind, you can find out if thoughts are consciousness or if they merely pass through consciousness. Are they you or just happening in association with you? And do you exist in the absence of thought?

These are important questions relating to the empty mind, a state transcending thought. Examining them is the first step in experiencing and using mushin in shodo.

Reflections and Reactions

Mushin is empty of thought like a mirror is empty. And the mirror is empty and full. It’s full in that a mirror always reflects something. Think about it: you’ve never seen a mirror without a reflection in it, and you probably can’t conceive of what its reflective surface would look like.

But it exists, and in this sense, the mirror must be empty. If it held onto one or more images, than anything new reflected in the mirror would have old images superimposed on it, resulting in a distorted view. People clinging to a past event do the same. They superimpose feelings about that event onto the present, modifying what they think they’re experiencing and not for the better. When the past is layered over the present, the present isn’t seen for what it is.

So the mirror only works when it lets go of past reflections. The mind works the same way, and when it does, mushin is present. In other words, mushin takes place when the mind is focused in the instant. It’s the current moment that’s not thought, not memory. It’s actually the only time we experience reality.

This is why mushin is associated with clarity of mind and appropriateness of reaction. This is also why it’s compared to a mirror-like state. The mirror only reflects when it’s empty.

We’re the same, and we realize mushin by keeping the mind in the moment (unless we deliberately choose to concentrate on the past or future). It’s in the moment that coordination of mind and body happens, in that the body only exists in the present. With unification of mind and body, we direct all our power, as opposed to just the mind or just the body, into an activity. It helps us realize our full potential, and when mind and body are coordinated, the body follows what the mind tells it to do. If you’ve tried shodo or even drawing, you know your hand doesn’t always accurately reproduce the picture in your mind. Unity of mind and body is needed, it occurs when the mind is in the present. Shodo and meditation encourage this.

It’s a condition in which perception is experienced without the immediate interference of thought. In short, when the mind is in the present, it’s empty. This doesn’t mean there are no reflections, meaning no perception of what our senses report. It means that the perception isn’t modified by memory and thus by conscious thought. Reality is perceived for what it is before being altered by thoughts stemming from the past.

You may be confused about thoughts versus perceptions, which makes it challenging to experience a condition beyond thought—mushin. A perception is something you hear, smell, feel, and so on via the senses. Everyone with a functional nervous system has these perceptions, and its unnatural—maybe impossible—to block them out. That’s true even during undertakings requiring deep concentration like meditation or art.

Why? Well, the more we resist noticing what our senses report, the more the mind focuses on these perceptions. So that doesn’t work.

Perceiving reality isn’t a problem. Creating an endless chain of often unwanted and meaningless chatter about these perceptions is the problem. That’s thought, not simple perception. And that happens a lot.

It makes us unable to rest, constantly being blitzed by our own thoughts about nothing of importance. Like Seinfeld, the “TV show about nothing,” but not nearly as funny.

Think of it like driving a manual transmission car. Sometimes you need to press on the accelerator, increase the revs, and make the car move. But when you stop, continuing to press on the go pedal only stresses you out, uses gas, irritates other drivers, and wears out your engine. You need to let the engine return to its natural idle. That’s what it wants to do anyway.

The mind is the same, and lots of us have forgotten how to let it return to idling. Mushin is the “idling mind.” It’s when the mind rests in the present, which should be our default mode. But it’s not, at least not for multitudes of folks who are continuously doing, striving, thinking, and wearing out their engines.

What Acts?

If our engine is idling, if the mind is empty—mushin, experiencing mu—then how did I throw my opponent as mentioned earlier? What acted? Not conscious thought, because I didn’t initially know how I did it.

But something made my body move in the right way, at the right place, and at the right time . . . pretty much a definition of effective action. But what acts?

Long ago in Japan, people interested in meditation and art forms potentially related to meditation—like martial arts and shodo—came up with analogies, metaphors, fables, and the like to explain what acts when the mind’s empty. Some of it is useful, some confusing, but rarely has it been updated for the 21st century. While I’m not suggesting abandoning timeworn accounts of mushin, I think it makes sense to use modern-day science and psychology to help us understand it. Unfortunately, the relationship between mushin and action isn’t a hot topic in scientific circles.

That, however, doesn’t mean the average person has no tools to fathom this. We know we have conscious and subconscious parts of the mind. We’re more aware of the conscious component, but we know the subconscious sways conscious action. You may have also heard of artists and musicians contriving unusual methods to “get the conscious mind out of the way,” so their art could stem from their unconscious. And quite a few of you probably know that repeated acts build up in the subconscious to become unconscious habits. We use these habits everyday, just as I’m using my subconscious to type without staring at the keyboard.

What’s more, you may have experienced trying to use a cultivated habit, only to be distracted by consciously thinking too much about what you’re doing. This is the absence of mushin. Not what I did or experienced in my judo example.

When I threw the other person my mind must have been in the present to recognize the opportunity to use my favorite technique. And remember, I drilled this skill everyday, creating a subconscious habit. So in a heightened state of perception, a state of not consciously thinking about the past or future, my subconscious noticed an opportunity to use a technique I’d practiced to the point of unconscious habit, and trained reflexes instantly took over. Some might label this “muscle memory,” a popular term these days for what is really motor learning.

Unfortunately, muscle memory implies that the body moves the mind, that the muscle has a brain. Probably not strictly accurate, it negates understanding of the subconscious. And that’s what really acts, but there’s still evidence of motor learning, an activity that’s been extensively studied in science.

It’s all about repetition, part of the reason I’ve spent over 30 years repeating basic brush strokes in shodo. But there’s more to it than that from a psychological and neurological perspective. The neuroanatomy of memory is unconscious and extensive throughout our brains. The conduits essential to motor memory are detached from the medial temporal lobe pathways connected with long-term memory: in this case conscious, deliberate recall of accurate information, past experiences, and ideas. Similarly, motor memory is hypothesized to have two stages: a short-term memory-encoding phase that’s unstable and vulnerable to loss, and a long-term memory consolidation phase that’s more secure. Simply, habits become stronger with additional repetition over time.

The initial so-called memory-encoding phase is what some term “motor learning.” To make it happen, we need an upsurge in brain activity in motor areas along with enhanced concentration. Brain areas operating throughout motor learning encompass the motor and somatosensory cortices. Nonetheless, these areas of operation decline once the motor skill is developed.

The prefrontal and frontal cortices are likewise operating throughout this phase owing to the need for augmented attentiveness tied to the undertaking being trained. But the central area related to motor learning is the cerebellum, a section of the brain involved in motor control. The basal ganglia, associated with thought, emotion, and voluntary motor movement, is also crucial to so-called muscle memory, in particular to stimulus-response associations and the development of habits. The basal ganglia-cerebellar networks are believed to intensify with time when absorbing a motor skill like shodo.

Over time, there’s a consolidation of muscle memory in the brain that forms habits. The how of this isn’t agreed upon by scientists, but everyone acknowledges that it takes place.

The takeaway is that when we do something difficult we tend to focus strongly on it. If we do this long enough and often enough, we create a subliminal pattern of action that’s encoded in the brain-muscle network as a subconscious habit. I don’t believe that the muscle literally remembers, but it’s clear the subconscious mind maintains records, as in the bike you never forgot how to ride.

Sadly, it’s not that simple.

Our conscious mind, specifically our thoughts, often gets in the way of motor learning, muscle memory, mushin, or whatever you call appropriate and spontaneous action. If this were not the case, given time we’d be experts at anything we tried, and we’d never screw up. But we do, and mushin ties into getting the conscious at least momentarily out of the way so unconscious ingrained habits can work for us. How do we do that?

- First, seriously drill whatever it is you want to acquire. (And don’t get complacent after a few years and slack off.)

- Second, bring the mind into the present, especially during the moment of performance. (This reduces pointless thoughts, which are frequently associated with the past or future. Don’t think yourself out of succeeding.)

- Third, relax but not in the sense of limpness of mind or body. Relaxing in a manner that’s not tense/not limp is vital for getting the conscious mind out of the way so unconscious habits can manifest themselves.

Do this and you’re on the way to discovering mushin.

No Mind or Empty Mind?

You may have seen mushin defined as “no mind,” while I’ve mostly referenced “empty mind.” Both translations are accurate, but I think the later is less prone to misinterpretation. No mind doesn’t mean zombie-like action and images of lobotomies shouldn’t pop into your head. But they do, which is why I often decipher mu in this context as “empty.”

No mind is tied to mushin no shin, the “mind of no mind.” That’s Zen folks encouraging us to drop attachments to thought, since we typically feel that our thoughts are our minds. Let go of conscious thoughts—“the mind”—and allow subconscious habits to work efficiently. Plus, in art the unconscious is seen as a resource for deeper creativity.

So long ago, some Asian people coined mushin no shin. It made sense in an era without a comprehension of the conscious and subconscious aspects of the mind, without research into motor learning. Today, maybe we can shorten this to mushin. Actually, you can call it whatever you want, but first you have to experience it, something this article and my books are designed to help you experiment with.

If you’re like many of my readers, you’ve probably read other accounts dealing with Japanese culture, meditation, and art forms. If you have, you’ve seen a plethora of technical terms connected to the psyche:

- Muga—“no self”

- Munen—“no thoughts”

- Mushin—“empty mind”

- Mushin no shin—“the mind of no mind”

- Fudoshin—“immovable mind”

- Munen Muso—“no thoughts, no mental images”

- Tenshin—“heavenly mind”

- Heijoshin—“peaceful, stable, everyday mind”

- And more

Japan has a huge number of words and phrases dealing with the mental state in meditation, shodo, tea ceremony, martial arts, and other disciplines. They’re worth looking into, but I’m not convinced they are inevitably separate from each other. With some exceptions, I think we’re talking about different ways of describing varying aspects of the same thing.

My house has four doors leading inside: a front door, two back doors, and a garage door. You can choose any door to get in, but depending on which you use, you’ll initially see a different view. To explain how to find the door, I’d use a different description for each as well. Regardless, once you’re in my house, after you stroll around a bit, you’d see that all the doors go into the same home.

Which door you use isn’t important. What’s important is that you actually walk over and come inside my house. (Not literally. Seriously, don’t show up inside my home uninvited. I love my readers, but not that much.)

Once you’re in the house, words and descriptions don’t matter. They’re just symbols used in the place of bona fide experience. To understand meditation, shodo, or any traditional Japanese art, start practicing and wait at least a year before trying to evaluate what you’re learning.

That long? Yes, that long.

Anything with depth and value can’t be understood in 10 easy lessons. If it can, you’ll be bored quickly, and I doubt you’ll get much out of it. Kobara Sensei practiced shodo over 70 years, only to comment toward the end of his time here, “Did you notice I changed the way I paint that kanji? It’s different now because I’m starting to get better at it.”

Using Thought to go Beyond Thought

Kobara Sensei wasn’t the first individual to mention mushin. I’m far from the first to write about it. And I hope I’m not one more author contributing to misconceptions relating to it, because misunderstandings are widespread. So are assumptions, one reason why I prefer teaching students with no prior shodo experience and people who haven’t read a ton of articles like this one.

While I accept most individuals as students, providing they can work within the program of instruction, there are reasons for the preceding sentence. One is that I’ve met quite a few people interested in shodo, who’ve read about mushin and think shodo amounts to “just spontaneously moving the brush and expressing my feelings.” It does, but not the way they assume. (Want to find out what a shodo teacher has to offer? Don’t assume anything; practice at least a year and have direct experience.)

Many people have read shodo parallels Western abstract expressionism and may have influenced it. I even wrote as much in the past, and it’s historically true. But don’t assume shodo is equal to abstract art. It has its own inimitable place in the art world.

Correspondingly, don’t assume abstract art is easy. Just splash paint on a canvas, right? Any six-year-old could do it, right? Except they don’t, and their “paintings” don’t end up in high-end galleries.

A related assumption is that abstract artists can’t execute realistic paintings. With a few allowances, most start by drawing conventional still life arrangements like other artists, and they have a fine grasp of the fundamentals of realistic art. They learned the basics with great rigor.

Based on the above assumptions, some folks are dismayed that classical shodo requires intense precision in the brush strokes. It’s perfected by copying samples of calligraphy, without even slight deviation. The teacher corrects every error in balance and form with red ink. No conscious expressing of creativity is allowed at first.

It’s all about repetition, absorbing the essence of shodo as it’s been passed down through the generations into the subconscious, absorbing something older and greater than our egos. Repetition equals motor learning. Not engaging the ego equals muga, a state beyond self-consciousness, beyond the conscious mind. Cultivating habits equals freeing the unconscious mind. Requiring intense precision equals bringing the mind into the moment.

Mushin.

People assume I’ve “mastered” basic shodo, so they’re occasionally surprised that I can spend several hours to several days experimenting with how I want to paint something, trying different inks and brushes. When I’ve entered my shodo and/or sumi-e in international exhibitions, I’ve worked on one idea for an average of four months before sending the best example. This is common among shodo artists, although probably not everyone.

Doesn’t this involve consciously thinking? Yes.

Is this mushin? Yes and no.

Deciding what brush or ink stick to use requires thought. Noticing how dissimilar types of paper react to various inks requires thought. Figuring out which script to brush requires thought. Looking at the end result and evaluating it requires thought and at times spur-of-the-moment, intuitive perception as well.

But the act of using the brush is in the moment, free from indecision and distracting thoughts. As a result, I practice repeatedly and deliberately to ingrain what I’m striving for into my subconscious, but when the time comes, I let all of that go. I focus the mind briefly and positively. Then I just relax and do it.

Mushin.

Is it creative? For sure, but not in the hyper-intellectual way Western art is sometimes presented. Is it spontaneous? Definitely, that’s where its clout comes from. It emerges from the infinite depths of my subconscious, from generations of shodo artists in my lineage, and ultimately from the universe that I’m part of.

What if it stinks? I learn from it. Nothing’s wasted. Then I let go of the past, ball it up literally, and throw it in a paper bag full of crumpled art.

And I move on to create something the same, yet fresh and different, possibly better. As long as life exists, there’s another chance.

So shodo uses thought and a condition beyond thought . . . at least transcending overtly conscious thinking. It’s simultaneously deliberate and free, impersonal and personal, hard work and effortless. Its beauty takes place suddenly and in the instant, but it’s based on decades of disciplined practice. It’s the hours of training, the years of constant self-reflection, and the depth of study that makes mushin in action possible.