In recent years, the popular Japanese art form known as etegami (e= image; tegami= letter) has captured the interest and imagination of artists all over the world. The simplest English definition of etegami may well be “Japanese postcard art.” But that phrase hardly does justice to the “the way” of etegami, and I’m happy to have this opportunity to give a fuller account of an art form I’ve been trying to promote through my blog to art lovers outside of Japan for almost twenty years.

“New Year’s Cards in Their Everyday Clothes”

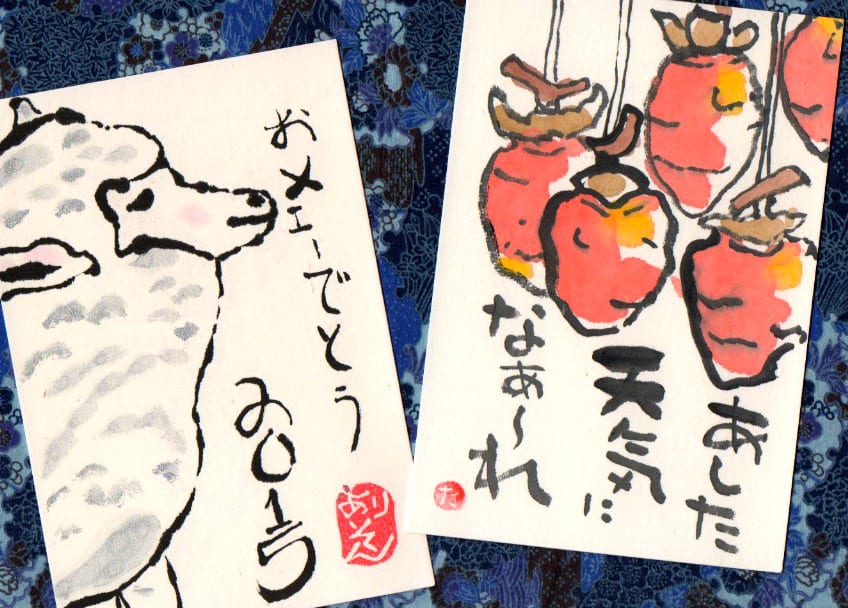

In 1873, when the Japan Postal Service first began to print standardized postcards, the traditional exchange of New Year greetings by letter (which dates back to AD 700s) suddenly became more affordable and popular than ever before. The set phrases used in traditional New Year’s greetings were ink-brushed onto the cards with a fine hand, often accompanied by an auspicious image such as Mt Fuji, red-crowned cranes, sea turtles, or the oriental zodiac animal of the new year.

The art form we now mean when we use the word “etegami” was conceived in the 1960s, when burgeoning calligrapher Kunio Koike became exasperated with the rigid traditions of his chosen field. He felt that the endless imitation of the masters was an exercise that diminished him. He longed for an art that did not require particular talent, years of training, or masters to demonstrate the “correct” form. He envisioned an art form that could be spontaneous, honest, and personal without being self-obsessed.

Koike began combining simple images with brief but thoughtfully chosen words on washi postcards, using tools and materials that had long been used in Japan’s traditional arts and were already familiar to him. He sent these postcards to a good friend with whom he explored the possibilities of his idea. He called this idea “New Year’s cards in their everyday clothes,” and created the slogan: Heta de ii. Heta ga ii, which can be translated “It’s okay to be awkward. Awkwardness has charm.” This wonderful slogan encouraged people who wanted to make art but had always felt they lacked the talent to do so.

The passion for etegami soon spread throughout Japan, and people began exchanging this form of postcard art through every season, rather than just at New Years. In 1996, Koike founded the Japan Etegami Society, which publishes a monthly magazine. Through the magazine, the Society sends out calls for etegami on specific subjects throughout the year, often displaying submitted works at the Society’s own etegami exhibition halls for public viewing.

Tools and Method

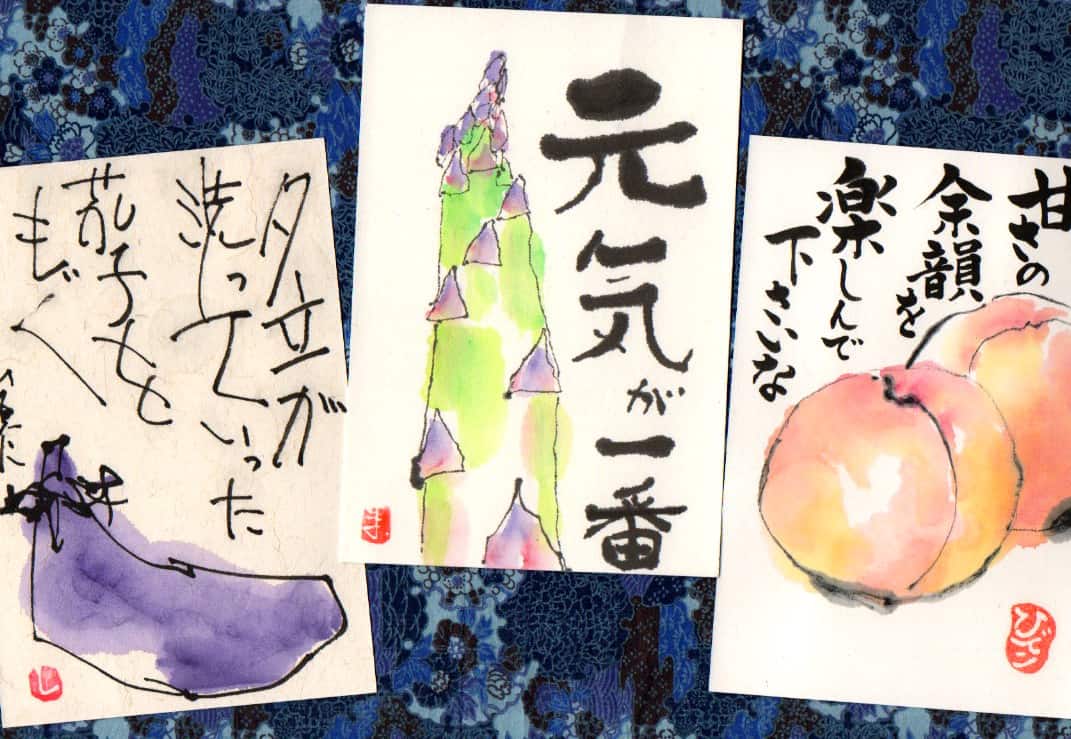

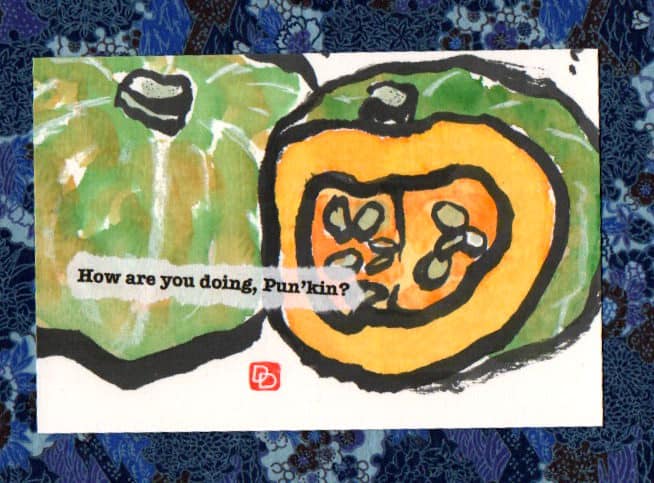

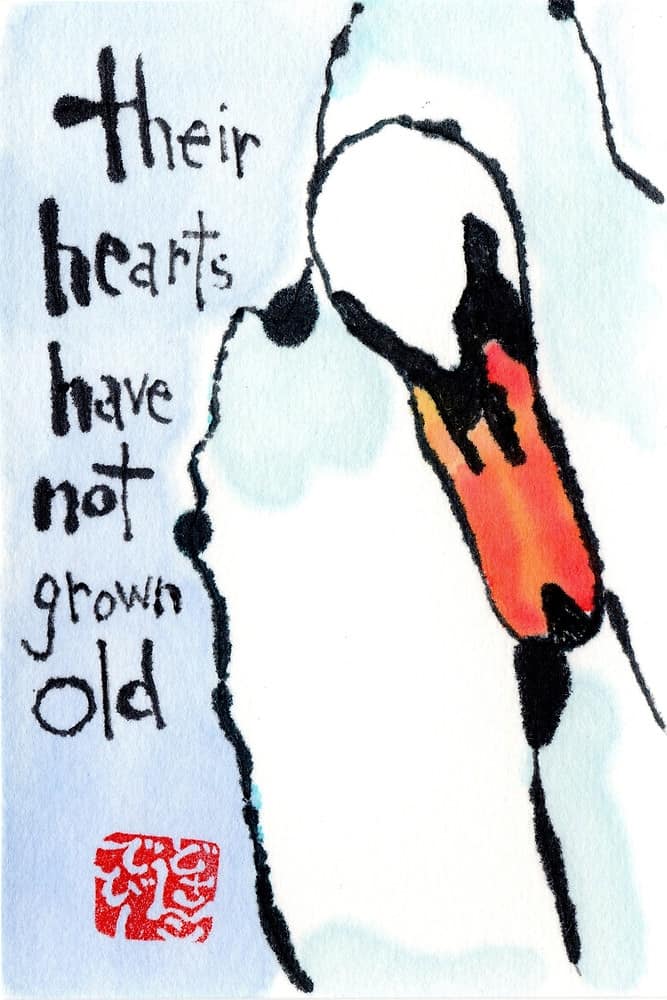

The standard tools and materials used in etegami include (1) a line-drawing brush (2) a coloring brush (3) liquid sumi ink (4) blocks of water-soluble, mineral-based gansai paints (5) a selection of washi postcards (called gasenshi) with varying degrees of bleed.

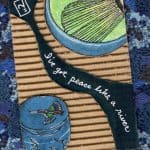

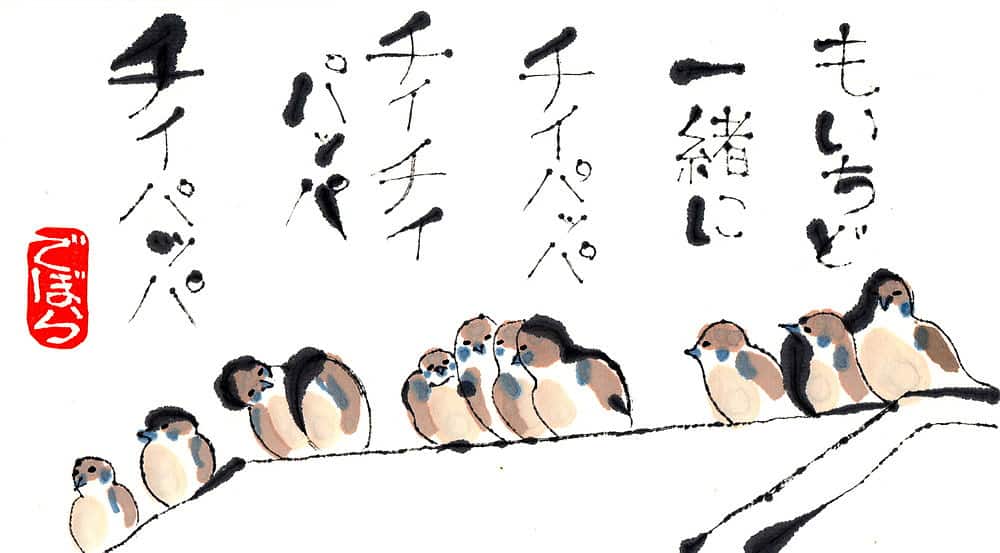

One distinctive characteristic of this art form is a desire to avoid total control of the process and the results. The lifted position of the elbow, the way the brush is loosely dangled perpendicular to the writing surface, and the extremely slow progress of the ink brush across the paper are some of the ways we strive to create “living lines,” the wobbly, often blotchy outlines of our subject.

Once the sumi outline is done, color is applied with the coloring brush, which requires no special handhold. Ideally, one “taps” rather than “strokes” the color onto the card, letting the color spread through the natural bleed (nijimi) quality of the washi card. The higher the bleed-rating of the card, the less control one has over the spread of the color, and this, too, adds character to the finished work.

Blank, unpainted space is important in etegami. We try to leave uncolored areas within the borders of the image, and the most orthodox etegami always have blank backgrounds.

We choose the subjects of our etegami from our daily lives, preferably items that reflect the season, such as fruits, vegetables, and seasonal flowers. Most often they are single subjects rather than items bunched together in some kind of staged still-life setting.

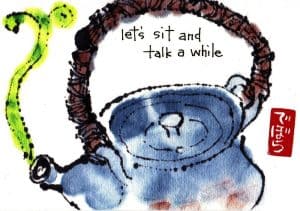

Ideally, the subject of an etegami is something that can be placed in front of us–something we can observe closely and touch. Painting from a photograph is discouraged, as is painting from the imagination. But– as I’ll explain later– once you’ve got the hang of orthodox etegami methods, it can be wonderful to depart from them and experiment with uncommon materials. An image accompanied by words, in a form that can be easily mailed to someone else– this is the basic requirement for etegami.

The Accompanying Words

Koike encourages us to use fewer rather than many words, and to avoid repeating information that the image already contains, so we would never accompany an image of an apple with the words “this is an apple,” unless it was meant humorously. Whether he chooses to use a writing brush and sumi ink, or a crayon, or a ball-point pen, the etegami artist aims at easy-to-read block letters rather than fancy calligraphy or elegantly cursive penmanship.

The finishing touch to an etegami is the placement of the hanko (chop), which serves as a signature. There is no “correct” place to press the hanko, so it can be anywhere the artist wants it to be. We generally do not use the fancy, stone-carved chops used by calligraphers and sumi-e artists. We typically make our own chops by carving the first kana syllable of our given name into rubber erasers, although there are endless variations.

Completing the Circle

“Catchers” are what Koike calls the people who are at the receiving end of our etegami. The sender is the “pitcher.” Catchers are a vital part of the etegami experience. We should be thinking of the intended recipient when we chose the subject and the accompanying words. Catchers help channel our focus outward, toward others, which keeps our etegami from turning into an exercise in self-absorption.

Every etegami we create should be posted to someone, even if we want to rip it up and toss it into the trash. We may be tempted to look at our work and think: “Does this piece reflect well on me?” or “Will the receiver admire me for this?” There is something very un-etegami in this way of thinking. Etegami is not about making ourselves appear skilled. Etegami is about enjoying the process, and about wanting to amuse, comfort, or maybe stimulate the mind of the receiver.

There are no master’s models in true etegami. Nor is there any place in etegami for drafts or underdrawings. Each etegami is a one-shot deal. Koike calls this a “shinken shoubu,” a phrase that means battling in earnest with real swords, as opposed to the wooden sticks and protective gear that are used in sword-fighting practice.

Further Adventures in Methods and Materials

Finally, there is plenty of room in this art form for departing from orthodox methods and materials, once one has grasped the heart of etegami. Thickened coffee can substitute for sumi ink; crayons instead of gansai paints. Pieces of an old bath towel wrapped around the tip of a chopstick can substitute for a brush; corrugated cardboard for washi postcards. Go ahead and paint from your imagination or a photograph, if you want to use a spaceship as your subject, and there are none handy in your neighborhood.

I have included photos of etegami painted by people from several different countries, including some of my own, using both orthodox and unorthodox methods and materials. Learn more about etegami from “The Beginner’s Guide to Etegami” a small but thorough book that is available from Amazon.com or my Etsy shop. The listing on my Etsy shop also provides a link to a downloadable, digital version of the book.

To learn more about Dosanko Debbie please visit her blog.