Nara, the ancient capital of Japan, seems worlds away from Tokyo and even Kyoto, especially in the bleak winter January month I chose to visit. In truth, I had been there several times, but this trip was to be a calligraphy supply buying trip in advance of my return to Boston. There is no hustle and bustle in Nara, and unlike Kyoto which is organized like a grid, one must do research and ask questions to find the places and areas one seeks for supplies. Yet for the purchase of ink, there is but one best destination which, at the time, had no website. It is Kobaien, located at 7 Tsubai-cho.

For over 400 years, sumi, 墨 Japanese for black ink sticks for calligraphy and sumi-e, has been made at Kobaien, founded in 1577 and recognized as the premiere ink making facility in Japan and in Nara where over 95 % of sumi is made. On my first visit there, I bought a few relatively inexpensive sticks of sumi. My level of calligraphy then did not seem to warrant investing in higher quality ink.

Perhaps it was an increased ability to speak Japanese and increased skill in calligraphy, perhaps it was very quiet in winter and the owner was not too busy, perhaps it was a question I asked. I have no idea for sure but was delighted to be invited to take a tour of the facility which has buildings on either side of a narrow road with a trolley track built into it for transport, all in back of the shop and well hidden from view.

Waiting for my eyes to adjust to the dark, the first building introduced to me was the place where soot is hand collected after it forms from the burning of branches such as pine to which pure vegetable oil such as rapeseed or sesame has been poured into unglazed earthenware on shelves which emit candle like light as the only illumination. It looks mysterious and stately. Small brushes used by skilled craftsmen collect the soot.

The next step in the process is to blend the soot with “nikawa” made into glue from cow skin or other animal skin which has been prepared in advance. While I did not see the very beginnings of the mixing of the two, I did see the space for preparing and keeping the “nikawa” liquid and at just the right temperature.

The craftsman kneads the mixture much like one kneads clay to remove air pockets and get a smooth and even product. There were three craftsmen kneading sumi in enclosed and small spaces. All were equally blackened by the process while intent on their tasks. The way to know that the kneading has been completed is by feel, and the craftsmen are in the top echelon of such knowledge.

The traditional technique for sumi production is followed by Kobaien collecting their own soot, whereas some other facilities purchase soot. Thus, from beginning to end, Kobaien follows the historical way of making sumi. It is said that the trees in Nara are particularly suited to making high quality sumi as the ink soot from the burned branches is likewise.

After the mixture for the sumi has the right consistency, fragrance is added before it is put into wooden molds. Otherwise, it is likely that the “nikawa” would have an unpleasant smell. The sumi lays side by side in wooden molds within a metal framework machine (non electric) which has the ability to press and release each ink stick. The photographs in this article will clearly show what is very difficult to explain in words.

The sumi is then carefully transferred to different levels of raw ash to remove moisture over time. Each stick is checked for moisture before moving on to the next level of the drying process. When enough moisture has been absorbed by the ash, some sticks are left to dry in the air. Others are wrapped in straw in a chain like fashion and hung to dry in small buildings which are carefully monitored for moisture content. The weather and time of year is always a factor in monitoring the ink drying phase. The process can take from two months to five years for the highest quality ink to mature and age, much like fine wine.

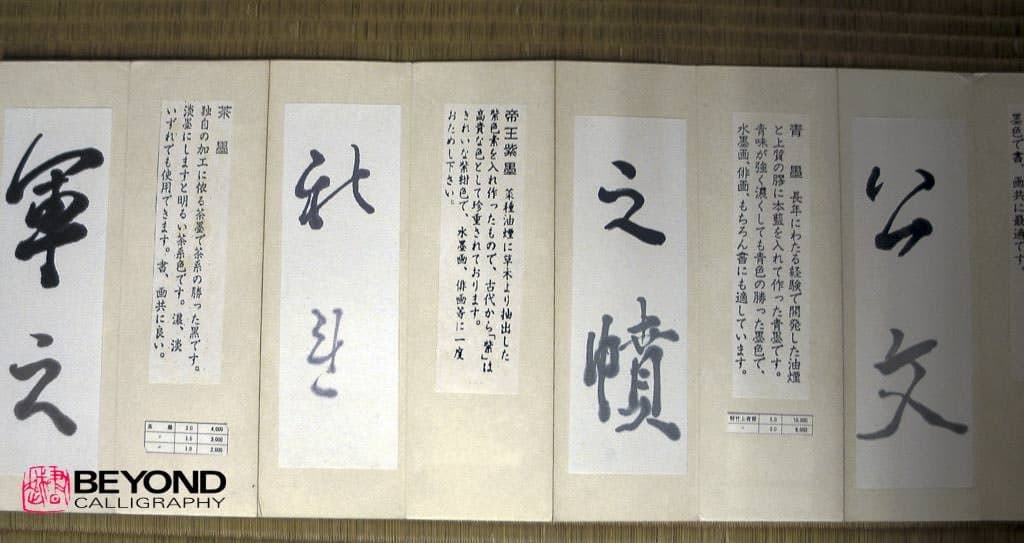

Inks are marked as to type with Kanji or , sometimes with gold, sometimes pressed shallowly into the ink itself. Some are polished/rubbed with a clam shell which gives a fine luster. And finally, some are decorated. Special boxes are made for each kind of sumi before they are put out for sale.

For centuries, ink made at Kobaien for calligraphy has been prepared by hand using inkstones or suzuri. Many sources describe the process which is slow and repetitive as a time for the calligrapher to settle into a meditative state before taking up the brush. There are many different sizes and qualities of inkstones, and each has its own rhythm and reacts with each ink differently. Making sumi is not something which can be rushed. The ink will be inferior and not interact with the brush properly. There is also the fact that ink, because of the nikawa ingredient, does not remain in good condition over time. Rather one should mix only as much as one needs for a day or so.

Thus arises a problem. If a calligrapher is making a large work, it is extremely time consuming to mix ink in sufficient quantities. At Kobaien, there were two electric machines for grinding ink. Presumably, since this was a store of the highest quality ink, they had chosen or recommended these machines. I bought the smaller one and brought it home. It was a great disappointment. It reminded me of when I taught ceramics to all ages including children. I used an electric Shimpo potters wheel of fine quality even with young students. Once in a while a parent would tell me that she or he had bought a potters wheel which turned out to be a great disappointment and frustrating for their children. I explained that the most important part of such a machine is the power of the motor. There was no comparison whatsoever with my Shimpo. With the small ink grinder, I found that I could grind ink more quickly than the machine, and it only made small batches.

As I began to do larger work and an opportunity presented itself, I was able to acquire a larger ink grinding machine. While it certainly works, as it turns out, one cannot grind ink quickly whether by hand or machine, as the ink quality will be quite inferior. My own Sensei does not have a machine. On the other hand, she often uses liquid ink for o-te-hon (teacher samples or book) to save time. I thought that one shouldn’t ever use liquid ink for any piece which one planned to back and have mounted into a scroll because the ink was not permanent and would bleed. Recent conversations seem to indicate the contrary which is a subject for another discussion.

What I can tell you without any hesitation at all is that in my experience, the quality for brushing and the tones and colors of a good to excellent sumi inkstick are far superior to any liquid ink.

Share your experiences in the comments below.