Some distinctive features of Huang Yao’s calligraphy

Many different scripts

Archaic awkward style

Painting in the background

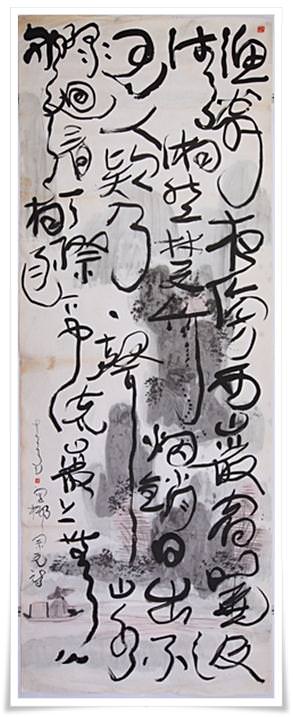

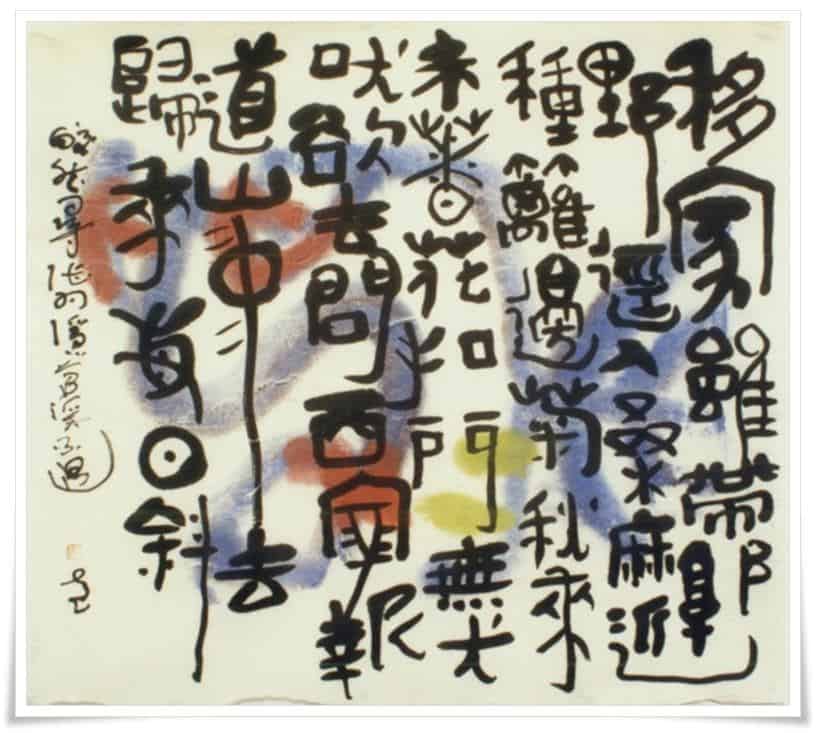

For variation, sometimes Huang Yao enhanced his calligraphy with splashes of color or shape in the background to accompany his calligraphy, example Figure. 6. The polychrome shape in the background is the character “shou” or longevity, but instead of being upright, it is lying on its side.

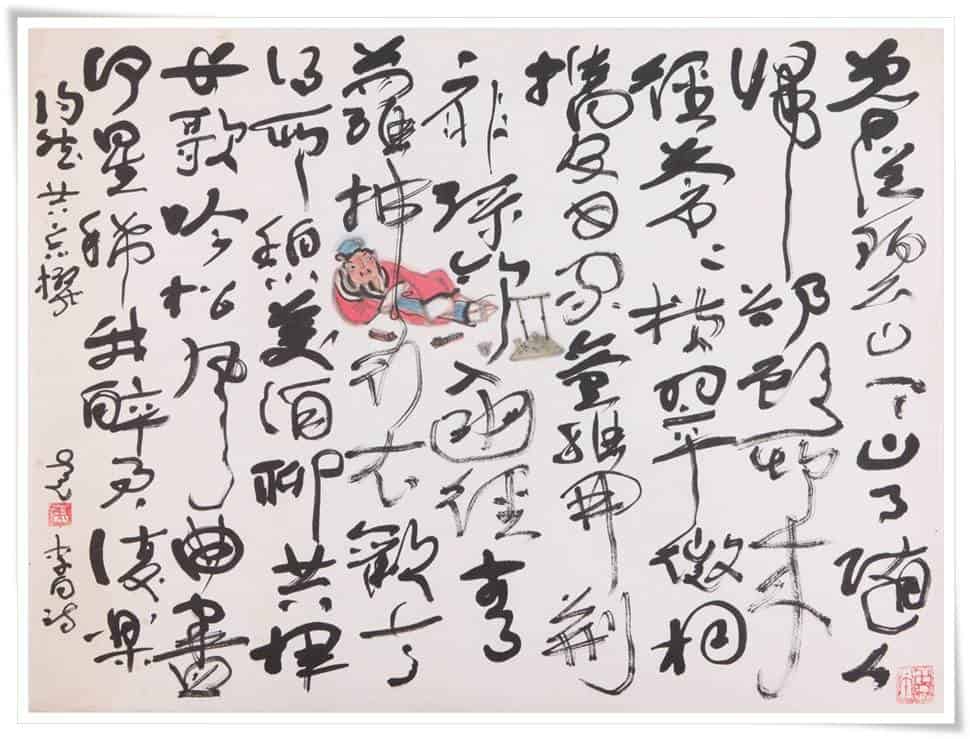

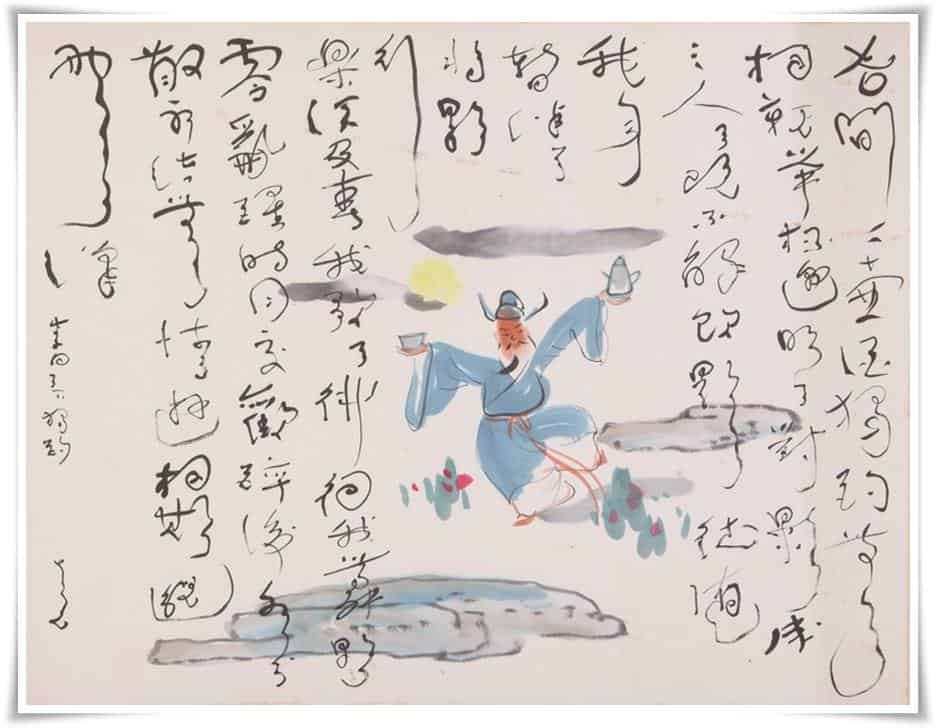

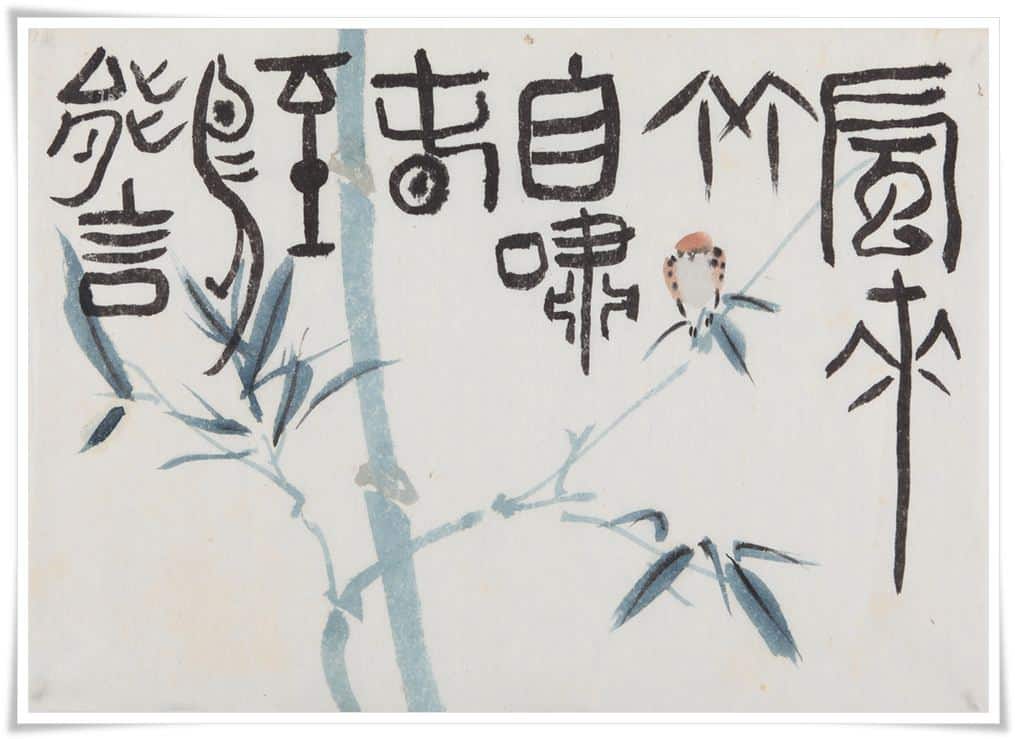

Use of painting to show meaning of the calligraphy, examples:

Expression of emotion

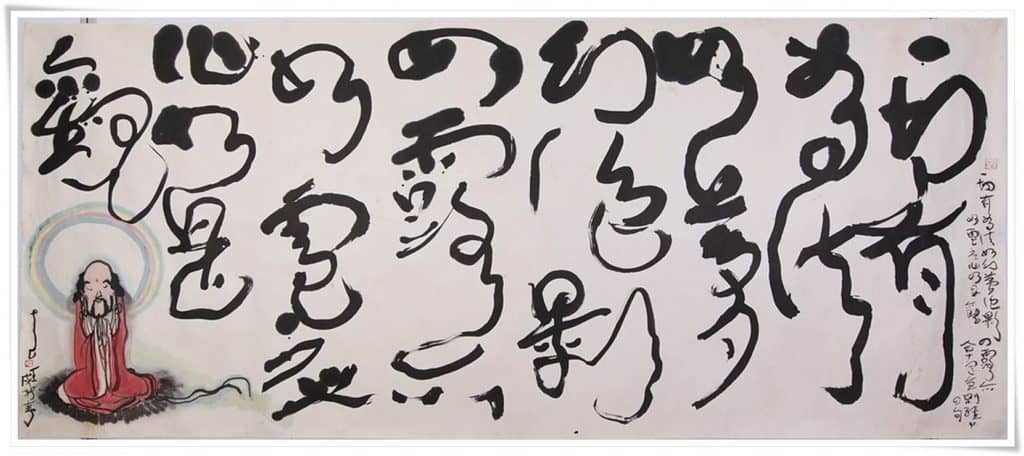

Huang Yao believed that Chuyun Shu should be a pleasurable way of writing. The calligrapher begins by relaxing both physically and mentally. With a peaceful state of mind, one’s innate dexterity is set free. Huang Yao would then write his favorite poems or verses in his usual order of strokes in the Chinese characters but upside down. Huang Yao considered Chuyun Shu as an unrestrained form of writing and best for spontaneity and speed, most suitable for caoshu where he was able to write characters fast without deliberation. This freedom in writing often allowed Huang Yao to express himself in a style that reflects the mood or emotion inspired by the meaning of the piece of the poem or verse. Figure. 10 is an example in expressing the rapid changes of the material world (The Diamond Sutra).

All compound things are like a dream,

a phantom,

a drop of dew,

a flash of lightning.

This is how to meditate on them or observe them.

Conclusion

Huang Yao had commented that there was really no secret to his ability to write Chuyun Shu in varying sizes, scripts and contents. People were curious and intrigued by this way of writing. He attracted large crowds whenever he gave demonstrations and he just wrote, wrote, and wrote happily. He felt that when he used Chuyun Shu the characters formed naturally, and not through conscious planning. He really thought it was just a lot of fun.

An interview regarding Huang Yao’s Chuyun Shu can be found at the link here.

For more examples of Huang Yao’s calligraphy, please refer to huangyao.org.

Part one of this article can be found here.

References:

1 Li Xianwen, “Zhongguo Meisu Cidian” (Dictionary of Chinese Art), Hsiung Shih Art Books Co.

Taiwan, Ltd., 2001. 1st edition by Shanghai Cishu Chubanshe, 1989.

2 Huang Yao, Shufa Rike or Daily Practice of Chinese Calligraphy, “Moyuan Suibi” (Jotting in

Relation to Ink), collected articles by Huang Yao, edited by Pan Qingsong, Kuala Lumpur:

Chinese Assembly Hall 2000, pp.122-125.

![Figure 5. Lou Shi Ming (A Simple Home) [177_08_38], Huang Yao Foundation](https://beyond-calligraphy.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Figure_5-huang_yao_unique_chinese_calligraphy.jpg)