1. Meaning:

forest, woods

2. Readings:

- Kunyomi (訓読み): もり

- Onyomi (音読み): シン

- Japanese names: もと

- Chinese reading: sēn

3. Etymology

森 belongs to the 会意文字 (かいいもじ, kaii moji, i.e. set of characters that are a combination of two or more pictographs, or characters whose meaning was based on an abstract concept). 森 follows a concept of three pictographs of a tree (木, き, ki) combined in one character, and it emphasises thick tree growth, i.e. woods.

The definition of the character 森 found in “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters” (說文解字, pinyin: Shūowén Jiězì) from the 2nd century C.E., compiled by Xu Shen (許慎, pinyin: Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.), a philologist of the Han dynasty (漢朝, pinyin: Hàn Cháo, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.), reads: 木多皃。從林。從木 (pinyin: Mù duō mào. Cóng lín. Cóng mù.), i.e., ”A thick growth of trees (in one area), from (the ideograph of) a thicket (林), from (the pictograph) of a tree (木).”

Curiously enough, the definition of the character for “tree” (木), found in the very same book, also suggests the meaning “emitting thick growth of plants (trees) over the land”. Today, words such as 林立 (りんりつ, rinritsu) or 森立 (しんりつ, shinritsu) mean “many objects (or people) standing lined up one aside another”.

A belief in Ancient Japan was that in deep thick forests abundant in huge trees, there are many places that had yet to be explored by humans, that the gods dwelt there, keeping their divine secrets to themselves. This Explains why the word “jinja” (神社, じんじゃ, i.e. “Shintou {神道, しんとう, Shintō} shrine”), as it appears in the Manyoushuu(萬葉集, まんようしゅう, Manyōshū, lit. “Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves”, the oldest collection of Japanese poetry, compiled in the second half of 8th century C.E.), was read “mori” (just like the character 森).

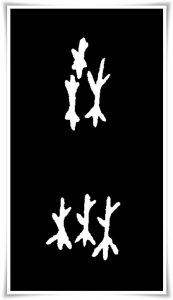

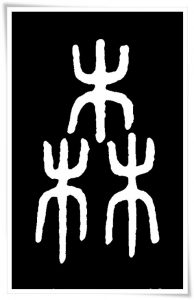

4. Selected historical forms of 森 .

Figure 1. Various oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun) forms of the character 森, Shang dynasty (商朝, pinyin: Shāng Cháo, 1600 – 1046 B.C.).

Figure 2. Ink rubbing of small seal script (小篆, しょうてん, shōten) form of the character 森, found in “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters” (說文解字, pinyin: Shūowén Jiězì) from the 2nd century C.E., compiled by Xu Shen (許慎, pinyin: Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.), a philologist of the Han dynasty (漢朝, pinyin: Hàn Cháo, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.).

Figure 3. Cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) form of the character 森, found in the calligraphy work entitled “Phonetic Dictionary in Cursive Script by The Ministry of Confucian Rites of Imperial China” (草書禮部韻, pinyin: Cǎoshū Lǐbù yùn ), by the Emperor Qian Long (乾隆, pinyin: Qián Lóng, reigned 1735 – 1796) of the Qing dynasty (清朝, pinyin: Qīng Cháo, 1644 – 1912 C.E.).

Figure 4. Ink rubbing of standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) form of the character 森, from the “Epitaph for Su Xiaocu” (蘇慈墓誌銘, pinyin: Sū cí mùzhì zhì míng, 538 – 601 C.E.), soldier and statesman of the Tang dynasty (唐朝, pinyin: Táng Cháo, 618 – 907 C.E.).

Figure 5. Semi-cursive (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) form of the character 森, found in the calligraphy by an outstanding Tang dynasty (唐朝, pinyin: Táng Cháo, 618 – 907 C.E.) calligrapher and high ranking official, Chu Suiliang (褚遂良, pinyin: Chǔ Suìliáng,597–658), entitled Ku Shu Fu (枯樹賦, pinyin: Kūshù fù, i.e.” Poem on the old withered tree”), 630 C.E.

5. Useful phrases

- 森林 (しんりん, shinrin): forest, woods

- 森閑 (しんかん, shinkan): silence

- 森森 (しんしん, shinshin): deeply forested

- 森の奥 (もりのおく, mori no oku): deep in the forest

- 森羅万象 (しんらばんしょう, shinrabanshō): all things in nature

Text: Ponte Ryūrui (品天龍涙)

English editing: Rona Conti

Japanese/Chinese editing: Yuki Mori (森由季)