1. Meaning:

ear

2. Readings:

- Kunyomi (訓読み): みみ

- Onyomi (音読み): ジ

- Japanese names: がみ

- Chinese reading: ěr

3. Etymology

耳 belongs to the 象形文字 (しょうけいもじ, shōkeimoji, i.e. set of characters of pictographic origin). It is a pictograph of a human ear.

說文解字 (shūowén jiězì, i.e. “Explaining Simple {Characters} and Analyzing Compound Characters”), by the philologist 許慎 (Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.), provides us with a definition of this character. There, one reads that “the ear is an organ governing hearing ability”.

Eyes and ears were considered to be organs which enabled some people to contact the divine spirit of the gods. Such virtuous individuals were referred to as “pure” (聖, せい, sei; also: “saint”). The etymology of the character 聖 indicates that this character is a member of 会意文字 (かいいもじ, kaii moji, i.e. set of characters that are a combination of two or more pictographs, or characters whose meaning was based on an abstract concept). It combines the idea of offering (呈, てい, tei) and 口 (さい, sai, where 口 stands for a sacrificial vessel used in rituals; read more here) and hope (望, ぼう, bō) for receiving blessings. The meaning of 耳 in 聖 is closely related to offerings to and listening to the voice of the divine. The oldest oracle bone script forms of 耳 from the early Shang dynasty period show a bent figure of a human being (kneeling or bowing while praying) with a large ear on top of it. If you refer to my article about the character 見 (けん, ken, “looking”, “viewing”), you will notice a great similarity between the concept behind both, as well as a virtually identical etymology (ideologically speaking).

The above should explain the etymology of the complex character which means “to listen”, written as 聽, nowadays simplified to 聴. As you can see, the “offering” (𤣩) radical was removed. The character 聽 incorporates “offering” and “listening” (耳 plus 𤣩), as well as well as “eyes” (目, め, me) and “heart” (心, しん, shin). The word 耳目 (pinyin: ěr mù) in Chinese means someone’s attention. It also refers to the fact that wisdom is gained through listening and watching. The character 心 has many meanings, and, in this case, it most likely stands for an “intention” to listen, and taking all of the words to heart.

The character 聽 and its unfortunate simplification, is a great opportunity for stressing how dangerous and linguistically unstable a character simplification can be. The main issue with modern simplified Chinese characters is that, etymologically speaking, they are indecipherable. Even if one doesn’t know a character or two within a text, he or she can still deduce the meaning from its radicals. If the essential components are removed or simplified, the characters become unreadable. I hope that this issue will be eventually recognised by the Chinese government and that proper and traditional forms of characters will be restored as they should be.

4. Selected historical forms of 耳 .

Figure 1. Ink rubbing of the Oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun) forms of 耳, from ca.1600 B.C. – 1200 B.C.

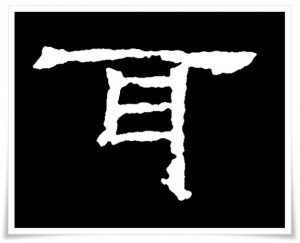

Figure 2. Small seal script (小篆, しょうてん, shōten) form of the character 耳, from the book 說文解字 (shūowén jiězì, i.e. “Explaining Simple {Characters} and Analyzing Compound Characters”), by the philologist 許慎 (Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.).

Figure 3. Ink rubbing of clerical script (隷書, れいしょ, reisho) from the stele 正始石經 (pinyin: Zhèng shǐ shí jīng), which records the text of the Five Classics (五經, pinyin: Wǔ Jīng) of Confucianism, the Three Kingdoms period (三國時代, pinyin: Sānguó shídài , 220-280 C.E.)

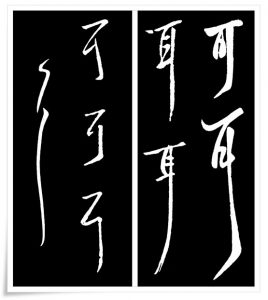

Figure 4. Ink rubbings of the cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) (left) semi-cursive (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) forms of the character 耳 (right). All characters are attributed to the Sage of Calligraphy (書聖; pinyin: : shū shèng) Wang Xizhi (王羲之, pinyin: Wáng Xīzhī, 303 – 361 C.E.) of the Jin Dynasty (晉朝, pinyin: Jìn Cháo, 265 – 420 C.E.).

Figure 5. Ink rubbing of the character 耳, taken from the stele 張猛龍碑 (pinyin: Zhāng měng lóng bēi), erected in 522 C.E. This example is reflective of the characteristics of the Northern Wei (北魏, pinyin: Běi wèi, 386 – 534 C.E.) dynasty standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho).

5. Useful phrases

- 耳目 (じもく, jimoku) – eyes and ears, someone’s attention

- 左耳 (ひだりみみ, hidari mimi) – left ear

- 早耳 (はやみみ, haya mimi) – quick-eared

- 初耳 (はつみみ, hatsu mimi) – something heard for the first time

- 耳鼻科 (じびか, jibika) – otolaryngology