1. Meaning:

child; first sign of Chinese zodiac; sign of the rat.

2. Readings:

3. Etymology

子 belongs to the 象形文字 (しょうけいもじ, shōkeimoji, i.e. set of characters of pictographic origin). It is a pictograph of an infant.

In “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters” (說文解字, pinyin: Shūowén Jiězì) from the 2nd century C.E., compiled by Xu Shen (許慎, Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.), a philologist of the Han dynasty (漢朝, pinyin: Hàn Cháo , 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.), we read: 十一月昜動。萬物滋。 (pinyin: Shíyīyuè yáng qìdòng. Wànwù zī.). It means that 子 is the Yang (昜 = 陽, yáng) element of the eleventh month (十一月) of the lunar calendar, which falls into the winter season. 子 is believed to be ruled by the water element (one of the four elements of nature that define the Chinese zodiac, and those are: 木 {pinyin: mù, i.e. “Wood”}, 火 {pinyin: huǒ, i.e. “Fire”}, 金 {pinyin: jīn, i.e. “Metal”}, 水 {pinyin: shuǐ, i.e. “Water”}), and it is under the control of the planet Mercury (水星, pinyin: shuǐxīng, lit. “Water Star”). Consequently, it is considered to be the force nourishing all living things (萬物滋).

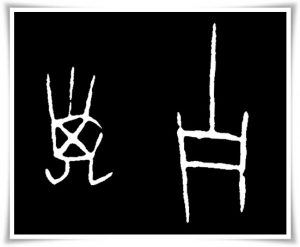

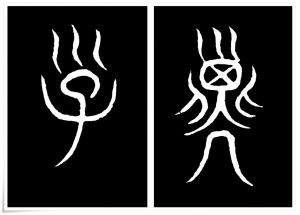

Although 子 is the first sign of the so called “twelve earthly branches” of the Chinese Zodiac (十二支, pinyin: shí èr zhī), i.e. the twelve animals, its seal script (篆書, てんしょ, tensho) form dating from the pre-Han dynasty period (i.e. before second century B.C.), so called 籀書 (pinyin: zhòu shū), was used to depict the sign of the snake (巳, pinyin: sì), the fourth month of the lunar calendar (summer season). See Figure 2. to compare. This form had already been written on turtle plastrons (shells) and bones incised in oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun) during the Shang dynasty (商朝, pinyin: Shāng Cháo , 1600 B.C. – 1046 B.C.). The form of 子 found in the divinatory texts (卜辞, pinyin: bǔcí) incised on turtle plastrons and animal bones during the Shang dynasty period, was once written as 㜽, with the 巛 (pinyin: chuān) on top of it, which symbolises (infant’s) hair (Figure 3).

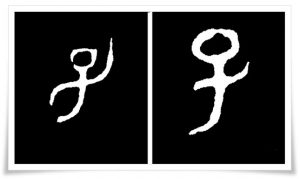

Some divinatory (卜文, ぼくぶん, bokubun) and kinbun (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metal”) script forms of 子 show a pictograph of an infant with one hand rising upwards and the other facing down (Figure 2). It was meant to symbolise “being worthy of the special social status of a ruler (or royal family members)”, and the origin of such a form is most likely associated with Prince You (王子友), who was made the Duke of Zheng (子鄭, pinyin: Zǐ Zhèng) in 806 B.C. He managed to establish the foundations for one of the strongest vassal states of the Spring and Autumn Period (春秋時代, pinyin: Chūnqiū shídài, 771 – 476 B.C.), after moving the court and most prominent merchants to the swampy and unpopulated area of Xinzheng (新鄭, pinyin: Xīnzhèng).

This theory would confirm the tradition present in later dynastic China of giving a courtesy name (字, pinyin: zì) to adult men (in their 20’s). Such a courtesy name, also known as 子某 (pinyin: zǐ mǒu; 某 literally means “such and such”), allowed for adding to the character 子 yet another character which would describe a given man’s point of view or philosophy. This concept corresponds to the significance and symbolism of the character 鄭 in 子鄭, i.e. the Duke of Zheng.

To illustrate this better, I will use the courtesy name of the disciple of Confucius (孔子, pinyin: Kǒng Zǐ, 551 B.C. – 479 B.C.) named Yan Hui (顏回, pinyin: Yán Huí, 521 B.C. – 490 B.C.). He took the courtesy name of 子淵 (pinyin: Zǐ Yuān, lit. “the child of abyss”, though 淵 may have the meaning of “revolving water”), which is in harmony and emphasises further the core teachings of Confucius himself. His famous quote is: “The wise take pleasure in rivers and lakes, the virtuous in mountains”. Both mountains and water are central phenomena to the Daoist concept of the world.

The later use of 子 in courtesy names originated during the Shang dynasty (商朝, pinyin: Shāng Cháo, 1600 B.C. – 1046 B.C.). At that time, 子 was added to names of rulers or royal family names as an honorific distinction. The ink rubbings (拓本, たくほん, takuhon) from various Shang dynasty artefacts (mainly bronze vessels, but also divinatory texts on animal bones) show that at least seventy of the names of rulers or their families included 子 in their real or courtesy names. If we look in a calligraphy dictionary, the number of ink rubbings and variety of forms of the character 子 is astonishing. The Great Calligraphy Dictionary (書道大字典, しょどうだいじてん, shodō daijiten) by Kadokawa Shoten (角川書店, かどかわしょてん), published in 1974, lists nearly 200 different forms of the character 子.

4. Selected historical forms of 子.

Figure 1. Two forms of the character 子 in oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun, c.a.1600 B.C. – 800 B.C.)

Figure 2. Left: Ink rubbing of the kinbun (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metal”) form of the character 子, taken from the wine vessel named 小臣兒卣 (pinyin: xiǎo chén ér yǒu), Shang dynasty (商朝, pinyin: Shāng Cháo, 1600 B.C. – 1046 B.C.). Right: Ink rubbing of the character 巳 (pinyin: sì, i.e. “6th earthy branch”, “Year of the Snake”, also “4th solar month {5th May to 5th June}”), found on the peculiar bronze wine container in the shape of a rhinoceros, named 小臣艅犠尊 (pinyin: xiǎo chén yú xī zūn), late Shang dynasty. Note the striking similarity of forms of those two characters.

Figure 3. Two forms found in the book “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters” (說文解字, pinyin: Shūowén Jiězì) from the 2nd century C.E., compiled by Xu Shen (許慎, Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.), a philologist of the Han dynasty (漢朝, pinyin: Hàn Cháo, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.). Left: small seal script (小篆, しょうてん, shōten); right: pre-Han dynasty great seal script (籀文, ちゅうぶん. chūbun).

Figure 4. Mature clerical script (隷書, れいしょ, reisho) form of the character 子. This ink rubbing comes from the late Han dynasty (漢朝, Hàn Cháo, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.) stele named 北海相景君碑 (pinyin: Běi hǎi xiān jǐng jūn bēi), 143 C.E..

Figure 5. Cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) forms of the character 子 found in works of the Ming dynasty (明朝, 1368 – 1644) literati Zhu Yunming (祝允明, pinyin: Zhù Yǔnmíng, 1460 – 1526 C.E.).

Figure 6. Ink rubbing of standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) of the character 子, from the stele 道因法師碑 (pinyin: Dáo yīn fǎ shī bēi) erected in 663 C.E., during the early Tang dynasty (唐朝, Hàn Cháo, 618 – 907 C.E). The text is attributed to Ou Yangtong (欧陽通, Ōu Yángtōng, birth date unknown, died 691 C.E.), who was the son of the famous Ou Yangxun (欧陽詢, pinyin: Ōu Yángxún, 557 – 641), also of the Tang dynasty.

Figure 7. Semi-cursive forms of the character 子 found in works of an outstanding ink painter and calligrapher of the The Song Dynasty (宋朝; pinyin: Sòng Cháo, 960 – 1279 C.E.) Mi Fu (米黻, pinyin: Mǐ Fú, 1051–1107 C.E.), also known as Mi Fei (米芾, pinyin: Mǐ Fèi).