1. Meaning:

month, moon

2. Readings:

3. Etymology

月 belongs to the 象形文字 (しょうけいもじ, shōkeimoji, i.e. set of characters of pictographic origin). It is a pictograph of a crescent moon.

According to 說文解字 (shūo wén jiě zì, i.e. “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters”), by the philologist 許慎 (Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.), the sound of the character 月 (げつ, getsu) corresponds with that of 闕 (けつ, ketsu, i.e. “lack”, also in Chinese “deficiency”) in the same way as the sound of the character 日 (じつ, jitsu, i.e. “day”, also “sun”) corresponds with that of 實 (じつ, jitsu, i.e. “truth”, also “reality”). Simply, the Moon was seen as the spirit (shadow) of the Sun; Yin (cold, dark and shadowy) opposing Yang (bright, positive and truthful); the Yin forces are represented by the “shadow” character (陰, かげ, kage), and the Yang forces by the “sun” character (陽, よう).

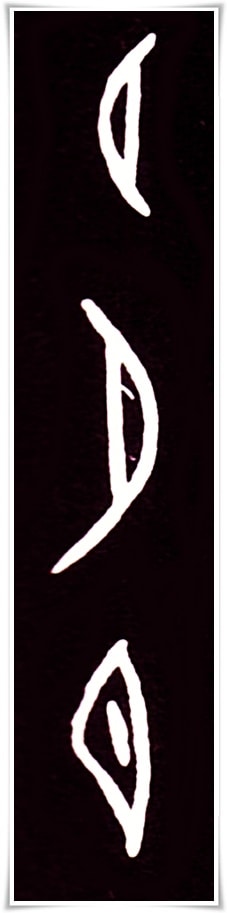

Similarly to 日, 月 was written with a small dot in the middle, representing an object. It is unclear what it represents, though there are many theories on this. There are forms of 月, however, that do not contain the dot. Those were the earliest forms of oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun), as shown in Figure 1.

Originally, 月 was written the way we see the crescent Moon from the Earth. In the process of stylisation it was turned on its axis. It is important to remember that at that time, for a period of some 2000 years (often referred to as The Age of Bamboo Slips), many characters were written on narrow bamboo (or other wood) planks known as mokkan (木簡, もっかん) in Japanese. Due to their oblong nature, many characters were elongated when written. You can observe this in one of our previous kanji etymology articles regarding the character 下 (した, shita, i.e. “below). The natural evolution of characters was stimulated by many practical and aesthetic factors.

4. Selected historical forms of 月.

Figure 1. Ink rubbing of the oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun) form of 月, from ca.1600 B.C. – 1200 B.C.

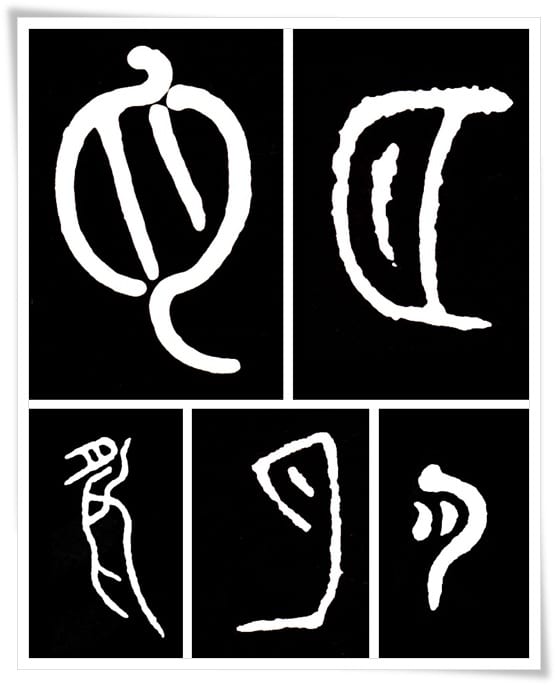

Figure 2. Various seal script (篆書, てんしょ, tensho) forms of the character 月, including kinbun (金文, きんぶん) and one of the decorative kinbun scripts known as chōchūten (鳥蟲篆, ちょうちゅうてん). The top-left is an ink rubbing from a calligraphy by a Chinese Confucian scholar and historian 莫 友芝 (Mò Yǒu zhī, 1811 – 1871). The top-right is a kinbun form found on a bronze vessel of the Zhou dynasty (周朝, 1046 – 256 B.E.). Note that it is turned on its axis 180 degrees. The bottom-left is an ink rubbing of the abovementioned chōchūten script, popular during The Spring and Autumn Period (春秋時代, 722 – 476 B.C.). This form was most likely found on a weapon, or a bronze decorative item. The middle-bottom is yet another form of the great seal script (大篆, だいてん, daiten), and the bottom-right is a form found on a seal.

Figure 3. Ink rubbing of the clerical script (隷書, れいしょ, reisho) form of the character 月, found on the stele 曹全碑 (Chinese: Cáo quán bēi), Han dynasty (漢朝, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.), 185 C.E.

Figure 4. Ink rubbing of the cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) form of the character 月, found in the Ming dynasty (明朝, 1368 – 1644) calligraphy by 祝允明 (Zhù Yǔn míng, 1460 – 1526).

Figure 5. Ink rubbing of the standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) at its ultimate and most outstanding stage of evolution, taken from the stele 温彦博碑 (Chinese: Wēn yàn bó bēi) by the brilliant Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907 C.E) calligrapher 欧陽詢 (Ōu Yáng xún, 557 – 641 C.E.).

Figure 6. semi-cursive script (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) script of the character 月. Ink rubbing from the calligraphy attributed to 王羲之 (Wáng Xī zhī,, 303 – 361 C.E.) of the Jin Dynasty (晉朝, 265 – 420 C.E.), who is often referred to as the Sage of Calligraphy (書聖; Chinese: shū shèng).