It is not an everyday occurrence to have the chance to visit a calligraphy exhibition with a tradition of 82 consecutive years. The 斯華会 (このはなかい, Konohana Kai) calligraphy association was founded by Master Ono Gadō (小野 鵞堂, おのがどう, 1862 – 1922)110 years ago. 鵞堂 (lit. “Goose Temple”) was the main pen name of Master Ono. Calligraphers may have alternate pen names, and it is not unusual. Master Ono sometimes signed his works as 斯華翁 (このはなおう, Konohanaō, i.e. “such a venerable flower”). 翁 also means “an old man”, which would suggest that this pen name was chosen in his later years. Thus, the origin of 斯華会 calligraphy association’s name is clear.

Master Ono was a great calligrapher in his time (明治時代, めいじじだい, Meiji Era, 1868 – 1912; 大正時代, たいしょうじだい, Taishō Era, 1912 – 1926). He was the one who laid the foundations for modern Japanese kana. Looking at works displayed during this particular exhibition confirms this fact. The event was not only replete with spectacular kana pieces, but also it showed that this particular calligraphy school has very solid foundations, going far back into the ancient history of calligraphy. Many works followed the so called “hidden spear” (藏鋒, ぞうほう, zōhō) style, a brush technique applied in some calligraphy scripts, though mainly in seal script (篆書, てんしょ, tensho) which is performed with a “rounded” stroke, referred to as enpitsu (円筆, えんぴつ, lit. “rounded brush”). This can be achieved through “hiding” the sharp “spear” of the brush tip, (formed with the hairs of the tuft), inside the line of a stroke, making them look rounded and smooth. In other words, while writing, the brush ought to be held at 90 degrees to the paper’s surface at all times, which assists in keeping the brush tip in the middle of the line, regardless of which direction one may be writing at the time. Such brushstrokes “lock” the energy within the lines, empowering and imbuing them with an ever-circulating spirit. The 行気 (ぎょうき, gyōki, i.e. “moving spirit”) in such works emanates from the black ink traces, mesmerizing the viewers. This technique was preferred by the Chinese calligrapher 王羲之 (Wáng Xīzhī, 303–361), traditionally referred to as the Sage of Calligraphy (書聖, Chinese: Shū shèng), of the Jin Dynasty (晉朝, 265–420). You may find it interesting, that geese were favorite pets of Master Xīzhī. It is said, that his brush technique and wrist movement were based on the way the geese turn their necks. He even built a pond in front of his house, which was named a “goose pond”. Master Ono’s choice of the pen name (“Goose Temple”) was most definitely a tribute to the great master of the brush – Wáng Xīzhī.

In this article, instead of simply explaining the meaning of what is written, I would rather focus on how the given calligraphy was written.

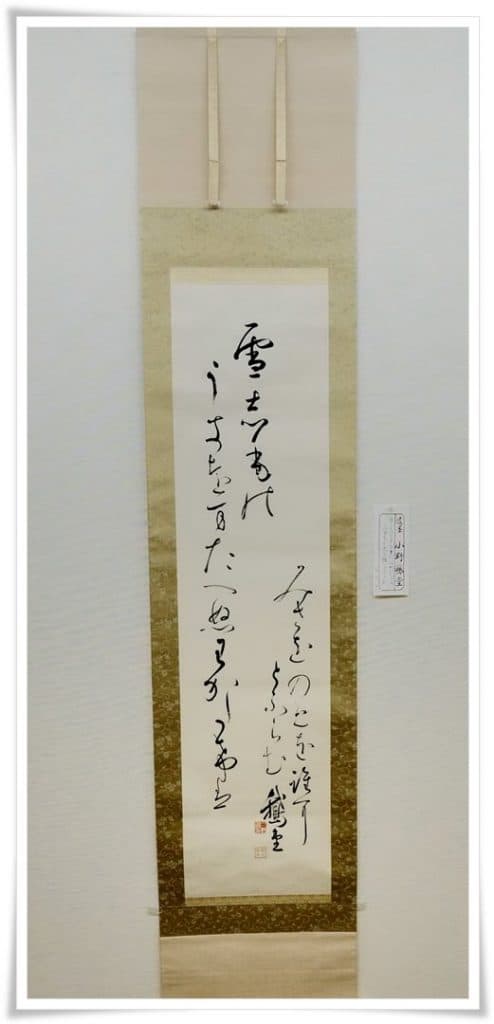

First let us have a look at Figure 3. It is a calligraphy in Japanese Kana script (かな) by Master Ono Gadō. Kana has many variants and there are multiple techniques that can be applied in one work. It takes great skill to combine one’s knowledge of the cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) and kana, while incorporating artistic arrangement of the text on the page. Kana is about the rhythm that serves as a bridge connecting the emotions of the artists with the meaning of the written phrase, as well as the composition. The calligraphy in Figure 3 merges two kana techniques. One of them is 散らし書き (ちらしがき, chirashigaki, i.e. “scattered writing”) and the other is 分ち書き (わかちがき, wakachigaki, i.e. “broken writing”). In scattered writing the calligraphy covers the sheet of paper in irregular patterns. The rows of kana start off at various heights which breaks the linkage between them, creating asymmetry. Going deeper into the philosophy behind this particular technique, we discover that scattered writing ought to depict the natural irregularity (and hence, the beauty) of a landscape and a far horizon, which blurs in the haze of a twilight.

Further, the placement of the signature is also very unusual. It comes at the left-hand side of the first row of text, and not at the end of the work (left side or bottom-left corner, optionally, at the bottom below the text), which is the traditional way of signing calligraphy. It breaks the monotony and introduces an element of surprise, spicing up the rhythm and enriching the composition. This technique is known as “maze writing” (女房奉書, にょうぼうほうしょ, nyōbōhōsho, lit. “court lady high quality writing paper”), a writing style created during the Kamakura period (鎌倉時代, 1185 – 1333), initiated by a female courtier of the Emperor Gonara (後奈良天皇, ごならてんのう, 1495 – 1557). Maze writing, as the name suggests, is a convoluted style in which the written word order is secondary to the composition.

Also, if I am not mistaken, Master Ono started off with writing the middle row, which would explain why the ink is so thick and dark there. Then, he proceeded to write the row to the extreme right. Then, he refills the ink before the second character from the bottom, and finishes the third line of text, ending just above his signature (two characters with red seals near them). The last row shows two more ink refills, and then one more on the signature. Thick and deep black lines combined with dry, pale lines are the rhythmical foundations of kana. They are the beating heart of the poetry of the brushstrokes.

…to be continued in Part 2.