1. Meaning:

flower

2.Readings:

3. Etymology

花 belongs to the 形声文字 (けいせいもじ, keiseimoji, i.e. phono-semantic compound characters). This is by far the largest group of Chinese characters, concluding about 85 – 90% of all kanji, which are composed of semantic (disclosing the general nature of a character) and phonetic (responsible for its sound, and often further narrowing the meaning of given character) elements. Usually, semasio-phonetic characters have a semantically corresponding version in a form of another character, of a more complex nature (so called 正字, せいじ, seiji, i.e. correct (traditional) characters; 花 is no exception here).

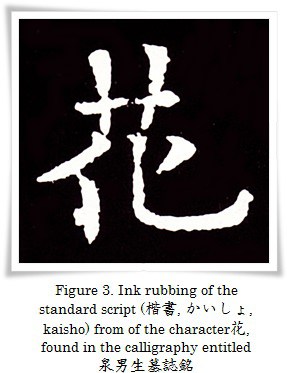

The phonetic part of the kanji 花 is 化 (か, ka, i.e. “action, change, etc.”). However, the 正字 of 花 is 華 (same reading / meaning, although different etymology). The seal script (篆書, てんしょ, tensho)form of the bottom part of the latter is a pictograph of a flower. The top part of 花 and 華 is a pictograph of the grass (a radical known as 草冠, くさかんむり, kusakanmuri, i.e. “grass crown”), or a ground plant (see Figure 1 and 3). The bottom part of 花 (化, か, i.e. “action of making something”, “change”) acts purely phonetically, although certain etymology theories suggest to take 化 as “a change” of the state of a plant (blossoming). It is also important to remember, that both 花 and 華 have multiple standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) forms.

Concluding, 花 is a semasio-phonetically simplified 華, although both characters have a separate etymology (same meaning, different origin). On the other hand, some dictionaries display them together (as one character with different forms), which may be confusing, and in my opinion, it is an incorrect classification. The origin of 花 goes back to the times of the reigns of 太武帝(Tài wǔ dì, 408-452), the third emperor of the Northern Wei dynasty (北朝, 386 – 534), and more precisely the year 425, when new characters were implemented via 新字千余 (Chinese: Xīn zìqiān yú, lit. “more than a thousand new characters”). For this reason (the timeline) 花 has no oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun) or clerical script 隷書, れいしょ, clerical script) forms. The shape of the seal script form(s) (Figure 1) of 花 strongly correspond with the ancient forms of the character 華, but in fact, they are not.

4. Selected historical forms of 花.

Figure 1. Ink rubbings of the seal script (篆書, てんしょ, tensho)forms of the character 花 (華), taken from the bronze vessels (small and large) 克鼎 (Chinese: Kè ding), Zhou dynasty, 10th century B.C.

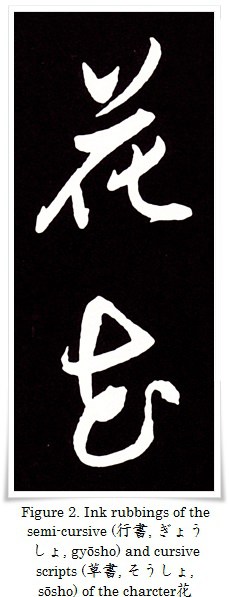

Figure 2. Ink rubbings of the semi-cursive script (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) and cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) of the character 花, found in the masterpieces of 祝允明 (Zhù Yǔn míng, 1460 – 1526), a famous calligrapher of the Ming dynasty (明朝, 1368 – 1644).

Figure 3. Ink rubbing of the standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) from of the character 花, found in the calligraphy entitled 泉男生墓誌銘 ( Quán nán sheng mù zhì míng) from 679 C.E. by 欧陽通 (Ōu Yángtōng, birth date unknown, died 691 C.E.), who was the son of famous 欧陽詢 (Ōu Yángxún, 557 – 641) of the Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907).