1. Meaning:

king, monarch, ruler, magnate

2. Readings:

- Kunyomi (訓読み): オウ、 -ノウ

- Onyomi (音読み): オウ、 -ノウ

- Japanese names: おお、 おおきみ、 わ

- Chinese reading: wáng, wàng

3. Etymology

王 belongs to the 象形文字 (しょうけいもじ, shōkeimoji, i.e. the set of characters of pictographic origin).

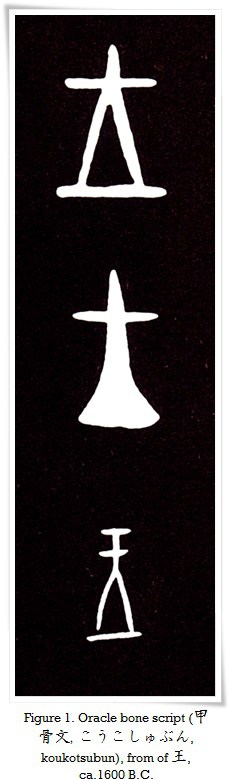

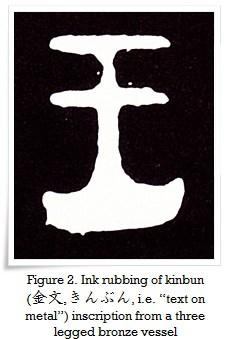

The oldest forms of this character from early Shang dynasty (商朝, 1600 – 1046 B.C.) are pictographs of a large axe (鉞, まさかり, masakari) blade (刃部, じんぶ, jinbu), as shown in Figures 1 and 2. The association of the axe with the ruler comes from a ceremonial axe that was kept near the throne, and was used for performing rituals in ancient China.

According to a work of a philosopher Dǒng Zhòngshū (董仲舒, 179-104 B.C.) of the early Han dynasty (漢朝, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.), titled 春秋繁露 (Chinese: chūn qiū fán lù, i.e. “Rich Dew of Spring and Autumn”), the shape of the character 王 has a symbolic meaning. The three vertical lines depict three powers: Heaven, Earth and Man (天地人, てんちじん, tenchijin), which are then connected by a vertical line symbolising the ruler bracing those powers and taking control over them. In his book we read: “王道通三 (Chinese: wáng dào tōng sān)”, which could be translated as “the way of the statecraft is (to gain) mastery over the three (powers)”. A similar political axiom was put forth by Confucius (孔子, 551 – 479 B.C.), four centuries earlier.

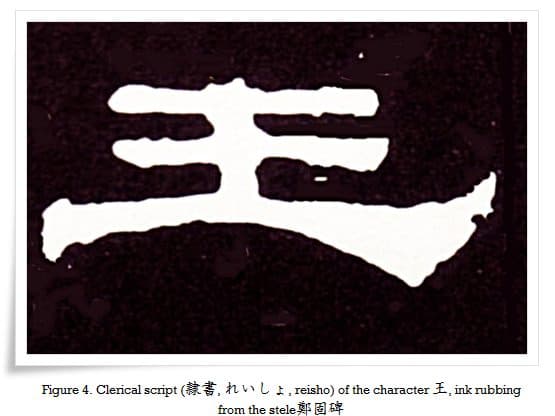

As you notice in figures 1 and 2, in comparison with figures 4 and 6, there is a significant difference in the distance between the two (or one, in case of the oracle bone script) top horizontal lines and the distance between the middle and the bottom lines. Starting from the 221 B.C. and the unification of great seal script (大篆, だいてん, daiten) under small seal script (小篆, しょうてん, shōten), the thickness of the bottom stroke (the one that depicts the axe blade) was standardised, however, the distance between the middle and bottom stroke was still more discernable than it was in later periods (it is quite evident in clerical script, see Figure 4). There is, of course, a reason behind this. The seal script form of the character 玉 (たま, tama, “sphere”, also a “jewel”), initially was mostly identical to 王 in form. The only difference was the distance between the middle and bottom horizontal lines (Figure 3).

In clerical script this distance was reduced, and a dot was added to the bottom-right of 玉, as the last stroke of this character (please see my article on stroke order to read more about it). Please compare the two characters (王 and 玉) shown in Figure 3 with those in Figures 4 and 6.

4. Selected historical forms of 王.

Figure 1. Oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun), from of 王, ca.1600 B.C. Note the clearly visible shape of a broad axe blade.

Figure 2. Ink rubbing of Kinbun (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metal”) inscription from a three legged bronze vessel (大盂鼎, Chinese: dà yú dǐng), from the early Western Zhou dynasty period (西周, 1046-771 B.C.), ca. 11th century B.C.

Figure 3. Small Seal script (小篆) forms of 王 (left) and 玉 (right). Both characters are ink rubbings taken from a calligraphy by 呉讓之 (Wú Xīzǎi, 1799 – 1870), a famous seal carver and calligrapher of the Qing dynasty (清朝, 1644 to 1912), the last dynasty of China.

Figure 4. Clerical script (隷書, れいしょ, reisho) of the character 王, ink rubbing from the stele 鄭固碑 (Chinese: zhèng gù bēi), from the Eastern Han dynasty period (東漢, 25 – 220 C.E.), 164 C.E.

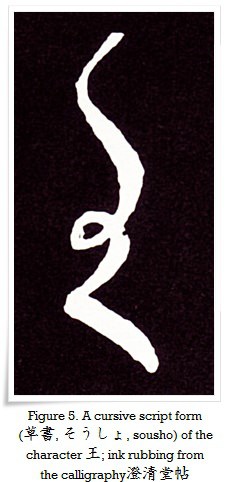

Figure 5. A Cursive script form (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) of the character 王; ink rubbing from the calligraphy 澄清堂帖 (Chinese: chéng qīng táng tiē) by 王羲之 (Wáng Xīzhī, 303 – 361) of the Jin dynasty (晉朝, 265 – 420).

Figure 6. Standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) of 王, ink rubbing from the stele 顔勤禮碑 (Chinese: yán qín lǐ bēi), by 顔真卿 (Yán Zhēnqīng, 709 – 785) of the Tang Dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907).

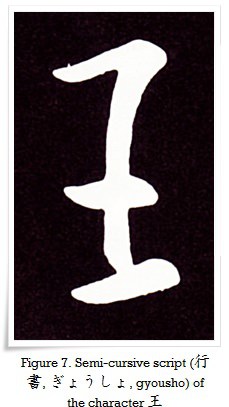

Figure 7. Semi-cursive script (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) of the character 王. Ink rubbing of calligraphy by 王導 (Wáng Dǎo, 276-339), a statesman of the Jin dynasty (晉朝, 265 – 420).

5. Useful phrases

- 王様 (おうさま, ōsama) – king

- 王国 (おうこく, ōkoku) – kingdom, monarchy

- 王子 (おうじ, ōji) – prince

- 女王 (じょおう, joō) – queen