1. Meaning:

one.

2. Readings:

3. Etymology

一 belongs to the 指事文字 (shiji moji, i.e. characters expressing simple abstract concept) group of characters. One theory says that the shape of kanji 一 is based on the 算木 (sangi), which were divination rods (small wooden sticks of a similar shape to matches, but longer and thicker). Sangi were also used for calculations. Another theory states that 一 is a pictograph of an extended finger. The latter theory does not, however, mean that 一 is a member the 象形文字 (shōkei moji, i.e. pictographic characters), as its meaning is not “finger”.

Given Chinese character may have many various forms, and they often significantly differ from one another. On the other hand, few different characters (of separate etymology) may bear identical meaning.

There are more kanji of the same meaning as 一. One of them is 壱 (ichi), which has another, more complex form: 壹 (hitotsu, number one). It was implemented to avoid confusion during writing between another form of kanji 一, which is: 弌 (itsu/ichi), and the ancient Chinese character 弍 (ni),  which means “two”. The form of 弌 (ichi) comes directly from the 古文 (kobun, i.e. ancient writing of the Shang and early Zhou dynasties, c.a. 1600 B.C. – 800 B.C. ). It was imitating the shape of kanji 弍 (ni, i.e. two).

which means “two”. The form of 弌 (ichi) comes directly from the 古文 (kobun, i.e. ancient writing of the Shang and early Zhou dynasties, c.a. 1600 B.C. – 800 B.C. ). It was imitating the shape of kanji 弍 (ni, i.e. two).

壱 is nowadays used in legal documents, for the purpose of avoiding mistakes with numbers, and also for preventing document falsifications. 弌 is in fact another variation of  character 一, whereas 壹 or 壱 are separate characters.

character 一, whereas 壹 or 壱 are separate characters.

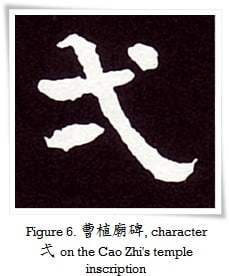

Lastly, please do not confuse 弐 and 弍. These are two separate characters. Another form of 弍 is 二, whereas the other form of 弐 is 貳. Confusing as it is, they all have similar readings and mean the same: “two” (this will be discussed further, when I will be writing about kanji 二).

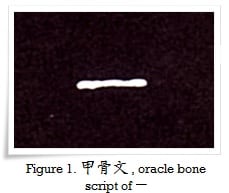

4. Selected historical forms of 一

Figure 1

古文 (ancient) form of 一. Oracle bone script form (甲骨文), from c.a. 1600 B.C.

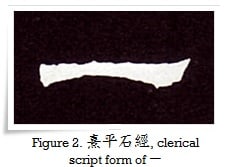

Figure 2

From the stele 熹平石經 (Chinese: Xī píng shí jīng) in clerical script, written during Eastern (Later) Han dynasty (後漢, 25 C.E. – 220 C.E.). Note characteristic”silkworm head” and “goose tail” (蠶頭雁尾, Japanese: santō gan-o), which are “trademarks” of matured Clerical script (八分隷, はっぷんれい, happun rei).

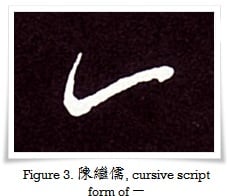

Figure 3

Cursive script (草書, sōsho) of 一. From one of the calligraphy works by 陳繼儒 (Chén Jìrú, 1558-1639) of the Ming Dynasty (明朝, 1368-1644)

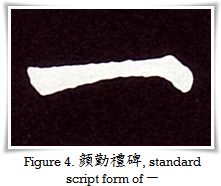

Figure 4

Standard script (楷書, kaisho) of 一. From the stele 顔勤禮碑 (Chinese: Yán qín lǐ bēi) by 顔真卿 (Yán Zhēnqīng, 709 – 785) of the Tang Dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907).

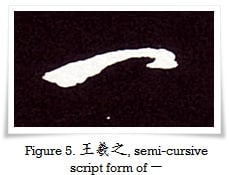

Figure 5

Semi-cursive script (行書, gyōsho) of 一. From one of calligraphy works attributed to 王羲之 (Wáng Xīzhī, 303-361) of the Jin dynasty (晉朝, 265 – 420 C.E.).

5. Selected forms of 弌

Figure 6

曹植廟碑 (Chinese: Cáo Zhí miào bēi, i.e. Inscription on the Temple of Cao Zhi (192 – 232 C.E.)).

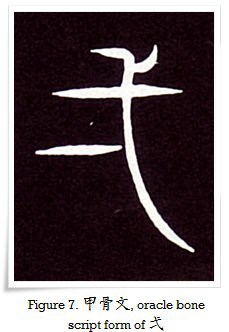

Figure 7

Oracle bone script form (甲骨文), from c.a.1600 B.C.

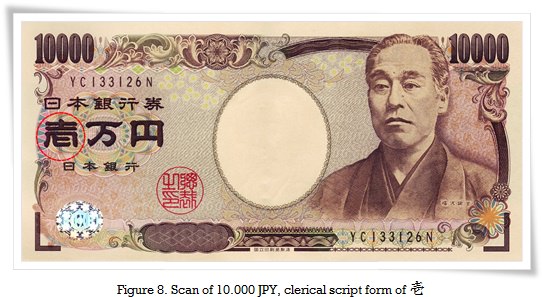

6. Example of 壱

Below (Figure 8 ) a scan of 10.000 JPY with a red circle around a Clerical script (隷書, reisho) form of kanji 壱 (mentioned above), as a real-life example of its official use in modern era. The text reads: 壱万円 (いちまんえん, ichiman en, lit. “(a single banknote of) ten thousand yen”).

If you happen to visit Japan one day, or perhaps, in case you are already living here, do not be surprised if you see kanji 壱 on a receipt or other documents. You will well know what it means.