1. Meaning:

mouth

2. Readings:

- Kunyomi (訓読み): くち

- Onyomi (音読み): ク、コウ

- Japanese names: Does not appear in Japanese names

- Chinese reading: kǒu

3. Etymology

口 belongs to the 象形文字(しょうけいもじ, shōkeimoji, i.e. set of characters of pictographic origin). It is a pictograph of an open mouth.

In 說文解字 (shūo wén jiě zì, i.e. “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters”) from the 2nd century C.E., compiled by 許慎 (Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.), a philologist of the Han dynasty (漢朝, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.), we read that 口 was “the cause for eating and speaking”. In kinbun (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metal”) and divinatory script (卜文, ぼくぶん, bokubun), examples of the phrase “mouth and ear” (口耳, こうじ, kōji), show that 口 was originally written in the same manner as the character for a sacrificial vessel 口 (さい, sai ), used for occult rituals (receiving benediction from the gods).

Numerous modern interpretations based on the study of the 說文解字 (shūo wén jiě zì, i.e. “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters”) are erroneous. For instance, the 口 radical in characters such as 古, 右, 可, 名, 各, 吾, 吉, etc., is in fact a pictograph of a ritual vessel or container and not a mouth. The modern meaning of the character 口 (mouth) is a later evolution, and although careful analysis of the kinbun (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metal”) and divinatory texts shows proof of the use of the character 口 in the earliest historical stages of Chinese writing, there is no clear evidence that would support the theory that the original shape of 口 was not in fact derived from that of the ritual vessel (see Figure 1).

4. Selected historical forms of 口.

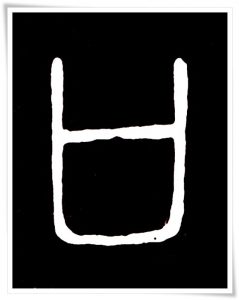

Figure 1. Various forms of the character 口 in oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun, c.a.1600 B.C. – 800 B.C.)

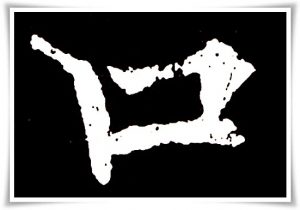

Figure 2. Seal script (篆書, てんしょ, tensho) form of the character 口, found in the book entitled 說文解字 (shūo wén jiě zì, i.e. “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters”) from the 2nd century C.E., compiled by a philologist of the Han dynasty (漢朝, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.), 許慎 (Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.).

Figure 3. Clerical script (隷書, れいしょ, reisho) form of the character 口. This ink rubbing comes from the temple stele 桐柏廟碑 (Chinese: Tóng bǎi miào bēi), erected during the Han dynasty (漢朝, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.)

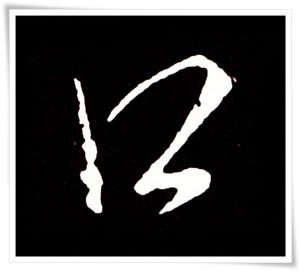

Figure 4. A very peculiar cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) form of the character 口, found in the Ming dynasty (明朝, 1368 – 1644), calligraphy by 祝允明 (Zhù Yǔnmíng, 1460 – 1526).

Figure 5. Ink rubbing of the standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) of the character 口, taken from the stele 道因法師碑 (Chinese: Dáo yīn fǎ shī bēi) erected in 663 C.E., during the early Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907 C.E). The text is attributed to 欧陽通 (Ōu Yángtōng, birth date unknown, died 691 C.E.), who was the son of the famous 欧陽詢 (Ōu Yángxún, 557 – 641) of the Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907).

Figure 6. Semi-cursive script (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) form of the kanji 口. Ink rubbing from the calligraphy work by 李邕(Lǐ Yōng, 678 – 747) Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907).

5. Useful phrases

- 入口 (いりぐち, iriguchi) – entrance

- 出口 (でぐち, deguchi) – exit

- 窓口 (まどぐち, madoguchi) – customer window (at a bank, post office, etc.)

- 火口 (かこう, kakō) – crater

- 口紅 (くちべに, kuchibeni) – lipstick