1. Meaning:

five

2. Readings:

- Kunyomi (訓読み): いつ、 いつ.つ

- Onyomi (音読み): ゴ

- Japanese names: い、 さ、 さつ、 ち、 ふ、 み、 め

- Chinese reading: wǔ

3. Etymology

五 belongs to the 仮借文字 (かしゃもじ, kashamoji, i.e. rebus (phonetic loan) characters; or in other words, characters that were borrowed phonetically to write another homophonic word.

The most ancient forms of the character 五 resemble the shape of two slanting wood pieces merged in the shape of the Roman letter X, forming a double sided receptacle. Alternate forms of this character also show a double lid, on the top and the bottom, covering the dish (for this reason, calligraphy dictionaries list this character under radical 二 (に, ni, i.e. “two”). The character 五、 etymologically, is unrelated to the modern meaning of the character 五, and its shape was borrowed purely for phonetic reasons. There is, however, one form of the character 五 represented by five diagonal parallel lines. It is most likely the earliest form of 五 that was replaced in later stages by a more complex rebus form (see Figure 1).

According to 說文解字 (shūo wén jiě zì, i.e. “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters”), by philologist 許慎、 (Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.), in ancient Chinese philosophy the Character 五 represents the five elements (or phases). They are known as 五行 (Chinese: wǔ xíng). Each of the elements plays its role in preserving the balance in the Universe, and they appear in both creative (positive element Yang (陽), and overcoming (negative element Yin (陰)) cycles:

The Generating cycle is as follows:

Wood (Chinese: 木, pinyin: mù) feeds Fire (Chinese: 火, pinyin: huǒ), Fire creates Earth (Chinese: 土, pinyin: tǔ) in the form of, Earth creates Metal (Chinese: 金, pinyin: jīn), Metal carries Water (Chinese: 水, pinyin: shuǐ), and Water nourishes Wood.

The Overcoming cycle is as follows:

Wood parts Earth (roots of the plants), Earth absorbs Water, Water quenches Fire, Fire melts Metal, and Metal cuts Wood.

Further, the symbolism of two lids located on the opposite sides of the dish could lead us to conclude, that the choice of the shape of the character 五 (Figure 1) was (perhaps) not purely phonetic, but was in fact an allegory of Heavens and Earth, Yin and Yang, and the joint sticks of wood were to be a symbol of interactions between the five elements.

Having said that,

and bearing in mind that the earliest forms of the characters were used for divinatory and occult purposes, the above may indicate that the character 五 could be classified as 指事文字 (しじもじ, shijimoji, i.e. “kanji whose shape is based on an abstract idea or concept”, and not a rebus (phonetic loan) character (仮借文字). Additionally, the characters for numbers 1, 2, 3, and 4 are all classified as 指事文字, and also all numbers do bear symbolic meaning related to occult rituals and beliefs. Nonetheless, 說文解字 (shūo wén jiě zì, i.e. “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters”) does not give the etymological explanation to the above, as well as does not explain the relationsship between the numbers. Since 說文解字 was not based on the knowledge of oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun), which was discovered in 1899, it would be impossible for the author to do so.

In summary, the in-depth analysis of the characters related to the ancient forms of 五, confirms beyond any doubt that 五 was indeed following the shape of a wooden receptacle equipped with two lids, and that indeed it is a phonetic loan character. For example, the former meaning of the character 吾 (ご, go, i.e. “I”) was “to protect”. 吾 was an ideogram of a ritual vessel used for receiving blessings (bottom part of the character, today written as 口, くち, kuchi, i.e. “mouth”), covered (protected) with a lid (五).

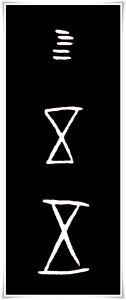

4. Selected historical forms of 五.

Figure 1. Ink rubbing of oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun) form of 五, from ca. 1600 B.C. – 1200 B.C. Note the radically different forms of the character 五 in its earliest stages of development.

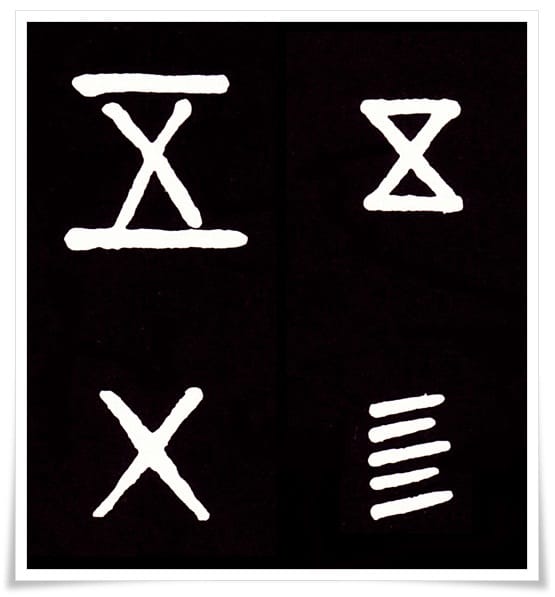

Figure 2. Various seal script (篆書, てんしょ, tensho) forms of the character 五. All four character are from the same period, Qing dynasty (清朝, 1644 – 1912 C.E.). The left two are the ink rubbings from works of the outstanding calligrapher and scholar 楊 沂孫 (Yáng Yísūn, 1813 – 1881), whereas the right-hand side examples come from works of the famous seal script scholar and calligrapher 呉 大澂 (Wú Dàchéng, 1835 – 1902 C.E.). Note that both forms of the character were still in use at that time.

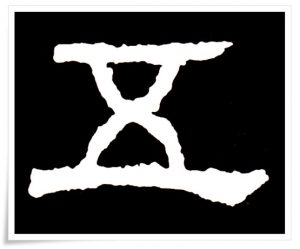

Figure 3. In rubbing of the clerical script (隷書, れいしょ, reisho) form of the character 五, found on the stele 白石神君碑 (Chinese: Bái shí shén jūn bēi) erected during the late Han dynasty (後漢, 25 – 220 C.E. ), 183 C.E. 白石神君碑 stele is an example of mature clerical script, also referred to as happun rei (八分隷, はっぷんれい, lit. “eight parts slave (script)”). Author is unknown.

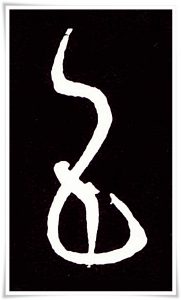

Figure 4. Ink rubbing of the cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) form of the character 五. According to the 書道大字典 (しょどう だいじてん, shodō daijiten, i.e. “The Great Dictionary of Calligraphy”, published in 1974 by 角川書店 (かどかわしょてん, Kadokawa Shoten), this form is to be found in the calligraphy entitled 風信帖 (ふうしんじょう, fūshinjō) by Kūkai (空海, くうかい, 774-835), a Buddhist monk, scholar and poet, who was possibly the greatest Japanese calligrapher of all time; Heian period (平安時代, へいあんじだい, 794 – 1185 C.E.). However, it happens so that only recently I have been practicing rinsho (臨書, りんしょ, i.e. “copying masterpieces”) of the very same text, and the character 五 does not seem to appear therein. This may be an error in the dictionary, which fact is quite interesting, and possibly could give a birth to a separate article. I will be consulting this issue with my calligraphy teacher, Master Kajita Esshū (梶田越舟, かじたえっしゅう, , 1938 – present) tomorrow, and elaborate on this further next week.

Figure 5. Ink rubbing of the standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) of the character 五, taken from the stele 道因法師碑 (Chinese: Dáo yīn fǎ shī bēi) erected in 663 C.E.; early Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907 C.E). The text is attributed to 欧陽通 (Ōu Yángtōng, birth date unknown, died 691 C.E.), who was the son of famous 欧陽詢 (Ōu Yángxún, 557 – 641) of the Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907).

Figure 6. Semi-cursive script Semi-cursive (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) script of the character 五. Ink rubbing from the calligraphy of a politician and famous Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907 C.E.) calligrapher 柳 公権 (Liǔ Gōngquán, 778 – 865 C.E.)

5. Useful phrases

- 五月 (ごがつ, gogatsu) – May

- 五年間 (ごねんかん, gonenkan) – period of five years

- 五百 (ごひゃく, gohyaku) – five hundred

- 五回 (ごかい, gokai) – five times

- 五階 (ごかい, gokai) – fifth floor