1. Meaning:

day off, rest, retire, sleep

2. Readings:

- Kunyomi (訓読み): やす.まる、 やす.む、 やす.める

- Onyomi (音読み): キュウ

- Japanese names: does not appear in Japanese names

- Chinese reading: xiū

3. Etymology

休 belongs to the 会意文字 (かいいもじ, kaii moji, i.e. set of characters that are a combination of two or more pictographs, or characters whose meaning was based on an abstract concept).

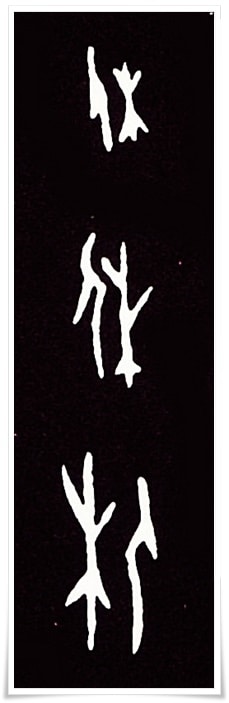

Comparing oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun) forms with some great seal script (大篆, だいてん, daiten) forms of 休 (Figures 1 and 2), it is clear that the 木 (き, ki, i.e. “tree”) radical was sometimes represented by 禾 (か, ka, i.e. two-branch tree radical; its original meaning was “growing grain”). As shown in Figures 1 and 2, the difference between the top part of 木 (き, ki, i.e. “tree”) and 禾 is evident.

It is highly probable that the 禾 was a reference to an announcement post (表木, ひょうぼく, hyōboku) at a (war) camp gate (両禾軍門, りょうかぐんもん, ryōka gunmon), where the achievements of a ruler or his army leaders were posted to allow passers-by to read about their heroism. The left-hand side radical 亻 (人偏, にんべん, ninben, i.e. “a person radical located at the left-hand side of a character”) is a pictograph of a person; in case of the kanji 休 it represents a person standing in front of such an announcement post.

Researching the etymology of characters such as 暦 (れき, reki, i.e. “calendar”), 歴 (れき, reki, i.e. “history”, but also “experience”), 厤 (れき, reki, i.e. “calculate”, also “calendar”), you will find out that all of those characters bear a reference to a (war) camp gate (all of the 木 radicals composing those characters were originally written as 禾). This confirms the theory that the character 禾 depicts the war camp gate pillars, or a centre mast. Thus, the original meaning of the character 休 was “to stop briefly (at the announcement post)” and read about distinguished (military) service of others (mainly kings or leaders)”. In fact, 休 still has such a meaning in modern Chinese language (i.e. to stop doing something for a brief period of time).

Analyzing the inscriptions in the earliest linguistically advanced script of the Chinese language known as kinbun (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metal”), we find an affirmation of this theory. Phrases such as 休寵 (きゅうちょう, kyūchō, i.e. “to pause (one’s actions) and cherish (someone))” or 休善 (きゅうぜん, kyūzen, i.e. “to stop for a while and admire others (who are) good at something”) refer to honouring those who excelled at something, by stopping for a while to learn about their outstanding deeds.

The character 休 appears in the short text incised on the 匡卣 (Chinese: Kuāng yǒu), a beautiful bronze wine jar from the Zhou Dynasty (周朝, 1046–256 B.C.), that was cast on the order of 周匡王 (Zhōu Kuāng Wáng, who reigned from 612 – 607 B.C.), the twentieth sovereign of the Chinese Zhou Dynasty, in the memory of 周懿王 (Chinese: Zhōu yì wáng, who reigned from 899 – 892 B.C.), the seventh sovereign of the Chinese Zhou Dynasty, and its meaning is “benevolent” (善), which is a reference to the actions of the aforementioned 周懿王.

The character 休 appears on numerous bronze vessels of various sizes throughout the history of ancient China, and even in old literature (such as 詩経 (Chinese: Shī Jīngand, i.e. “The Book of Odes” which is a collection of poems composed between 10th and 7th century B.C.)), and its meaning was always related to publicly displaying information about good deeds and military achievements, and especially those of kings and leaders.

In later stages, from the original meaning of 休, wider interpretations including “prestige”, “honour”, or “special favour” (from the ruler, as a token of gratitude)”, etc., were attributed to the character (such as “休善”, mentioned earlier on). This meaning was narrowed down throughout the millennia to “stopping for a while”, and eventually “resting”, through phrases such as 休息 (きゅうそく, kyūsoku, i.e. “rest”, or “relaxation”. The latter can be literally understood as: “to pause for a while to catch your breath”).

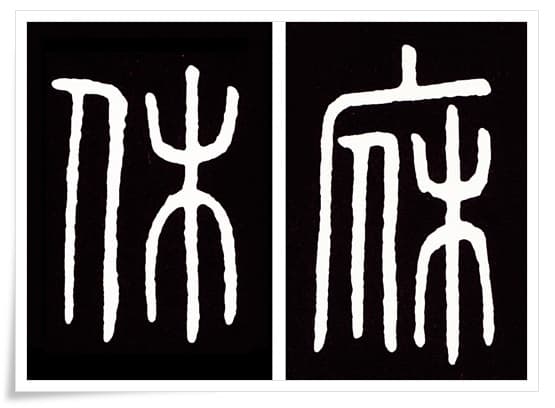

Lastly, the multilevel evolution of the character 休 can be observed by comparing its seal script forms, such as those found in 說文解字 (shūo wén jiě zì, i.e. “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters”) from the 2nd century C.E., compiled by 許慎 (Xǔ Shèn, ca. 58 C.E. – ca. 147 C.E.),a philologist of the Han dynasty (漢朝, 206 B.C. – 220 C.E.). As shown in Figure 3, you see two out of at least five variants (so called 異体字, いたいじ, itaiji) of the kanji 休 (i.e. 庥 and休). The 異体字 of a given character may vary quite significantly in form, though they all bear the same, or closely related, meaning.

4. Selected historical forms of 休.

Figure 1. Various oracle bone script (甲骨文) forms of the character 休.

Figure 2. Ink rubbing of the kinbun (金文, きんぶん, i.e. “text on metal”) form of the character 休, taken from a small bronze food vessel 史頌簋 (Chinese: Shǐ sòng guǐ), late Eastern Zhou dynasty (西周, 1100 – 771 B.C.). Note that the upper part of the right-hand side radical of this character is bent up and to the left, indicating the original application of 禾 instead of 木.

Figure 3. Two kanji variants (休 and 庥) of the character 說文解字 (shūo wén jiě zì, i.e. “Explaining Simple (Characters) and Analyzing Compound Characters”). Since the etymology of kanji is very complex, and spread throughout thousands of years, it is not uncommon for Chinese characters to have many semantically identical, yet visually different forms. Yet another form of 休 (𠇾) can be observed in Figure 7.

Figure 4. Ink rubbing of the clerical script (隷書, れいしょ, reisho) form of the character 休. This particular calligraphy was found on the remains of 朝侯小子碑 (Chinese: cháo hóu xiǎo zǐ bēi) stele from the late Han dynasty period (後漢, 25 – 220 C.E.).

Figure 5. Cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho) form of the character 休, found in the calligraphy work entitled 澄清堂帖 (Chinese: Chéng qīng táng tiē) attributed to 王羲之 (Wáng Xīzhī, 303 – 361), often referred to as the Sage of Calligraphy (書聖; Chinese: shū shèng), Jin Dynasty (晉朝, 265 – 420 C.E.). The original work did not survive (in fact, none of his original works exist), and the rubbing was taken from a stele erected during the Ming dynasty (明朝, 1368 – 1644 C.E.).

Figure 6. Ink rubbing of standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) form of the character 休, taken from the Jiucheng Palace stele (九成宫碑, Chinese: Jiǔ chéng gōng bēi), Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907 C.E.).

Figure 7. This is a semi-cursive script (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) form of the character 𠇾 which is one of the variants of the kanji 休. This particular form was found in the calligraphy by a brilliant Chinese calligrapher and ink painter 趙孟頫 (Zhào Mèngfǔ, 1254 – 1322 C.E.), written during the Yuan dynasty (元朝, 1271 – 1368 C.E.), founded by the Mongolian leader Kublai Khan.

5. Useful phrases

- 休日 (きゅうじつ, kyūjitsu): holiday, day off

- 休止 (きゅうし, kyūshi): pause

- 休意 (きゅうい, kyūi): peace, tranquillity

- 休心 (きゅうしん, kyūshin): rest assured

- 休暇 (きゅうか, kyūka): holiday, day off