1. Meaning:

sound, noise, note (music)

2. Readings:

3. Etymology

音 belongs to the 会意文字 (かいいもじ, kaii moji, i.e. set of characters that are a combination of two or more pictographs, or characters whose meaning was based on an abstract concept).

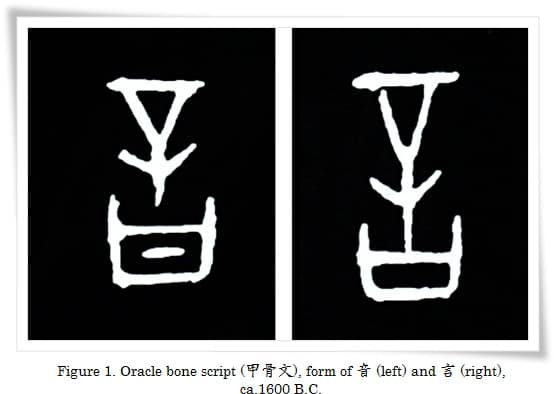

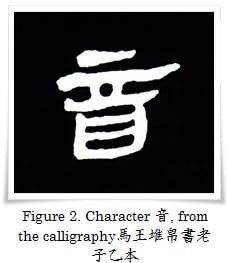

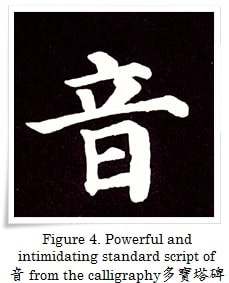

Despite the visual differences of modern forms, the characters 音 and 言 (いう, iu, i.e. “to speak”) have identical 古文 (こぶん, kobun, lit. “ancient text”) forms (Figure 1) of the top radical, however, the bottom parts of both characters slightly differ from each other. The bottom radical of both kanji is a pictograph of a vessel that was used for receiving blessings called さい (“sai”), and not a pictograph of a mouth (口, くち, kuchi) with a tongue inside, as many sources erroneously suggest, (click here to compare with the etymology of the character 右). Originally, the difference between those two characters was the horizontal line inside the ritual vessel pictograph of the character 音 (Figure 1 (left) or Figures 2 and 4) which symbolises the sound of the voice of the person performing a religious ritual.

However, due to the identical shape of both radicals (口, and さい), especially the forms written in 卜文 (ぼくぶん, bokubun, i.e. “divinatory text”), as well as a strong semantic connection between them (communicating with Gods through a vessel, that was also symbol of the voice of Gods), both radicals are displayed in dictionaries under 口, beginning with the earliest scripts (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun, i.e. “Oracle bone script“, and 金文, きんぶん, kinbun, i.e. “text on metal”). This may be quite misleading if not studied in depth.

The upper part of 音 is evidently connected with 言. The top part of the kanji 言 (and 音) is a pictograph of a needle, 辛 (しん, shin), used for performing ritual tattoos on individuals taking oaths during a ceremony (言 = 辛 + (さい, sai, i.e. “ritual vessel”). The seriousness of the oath was strengthened further by the ritual tattoo. 音 symbolises the internal voice of one’s heart, released verbally, in order to communicate with the Divine. The ritual vessel and the needle were to emphasise the inevitability of the Gods’ wrath if the oath was taken in bad faith, or not fulfilled. The ancient form of the character 音 was closely associated with the retaliation of the Gods (the voice and fury of divine beings).

The etymology of both kanji is very similar, which also explains why some forms of the seal script (篆書, てんしょ, tensho) of 音 and 言 are completely identical (they look as as shown in Figure 1, right-hand side form of the character 言). It is possible that 音 and 言 were used interchangeably in the earliest stages of the history of Chinese writing.

Meaning of the word “sound” (音) is also closely related to music, which was understood as a sound that originates in the artist’s mind (similarly as it happens during the religious ritual; speaking the words one is thinking of), and then is transformed into music, flowing through the musical instrument. This led to the modern general meaning of sound.

4. Selected historical forms of 音.

Figure 1. Oracle bone script (甲骨文), form of 音 (left) and 言 (right), ca.1600 B.C. Note that both characters share the same upper radical. The bottom part may be somewhat misleading; the bottom radical of the character 音 is a vessel that was used for receiving blessings (called さい, “sai”) with a horizontal line inside it that symbolises the sound of a voice, whereas the bottom radical of the character 言 is 口 (くち, kuchi, i.e. “mouth”)

Figure 2. Character 音, from the calligraphy 馬王堆帛書老子乙本 (Chinese: Mǎ Wángduī bó shū Lǎo Zǐ běn), discovered in the Mǎ Wángduī archaeological site in 長沙 (Chinese: Chángshā), written by the legendary 老子 (Lǎo Zǐ, the founder of Taoism). Ink on silk, early clerical script (隷書, れいしょ, reisho).

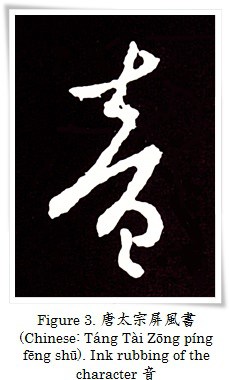

Figure 3. 唐太宗屏風書 (Chinese: Táng Tài Zōng píng fēng shū). Ink rubbing of the character 音, taken from the calligraphy by the emperor 太宗 (Tài Zōng, 626 – 649) of the Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907) in cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho), originally written on a folding screen (called 屏風, びょうぶ, byoubu in Japanese).

Figure 4. Powerful and intimidating standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho) of 音 from the calligraphy 多寶塔碑 (Chinese: Duō; bǎo tǎ bēi), by 顔真卿 (Yán Zhēnqīng, 709 – 785) of the Tang dynasty (唐朝, 618 – 907), ink rubbing of the stele erected in 752 C.E.

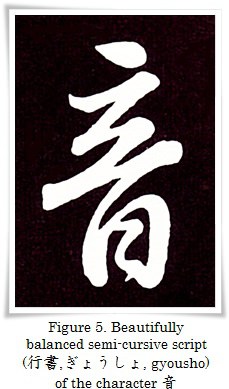

Figure 5. Beautifully balanced semi-cursive script (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho) of the character 音. Ink rubbing of the calligraphy by 董其昌 (Dǒng Qīchāng, 1555 – 1636), Ming dynasty (明朝, 1368 – 1644).