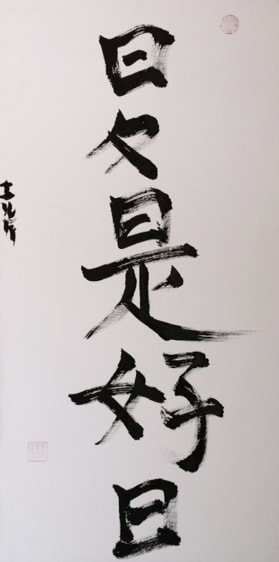

Mastering calligraphy is a lifelong journey. It requires practice, dedication, failure, and practice again. Never will there be a moment that work has reached the status of perfection. Nevertheless, one has to take the plunge at some point and show the work to the world. Thus, I have recently launched a website, deciding that now is as good a time as any.

Having travelled to Japan a few years ago, I took my first calligraphy course there and got inspired. I have dedicated my time to practice and training ever since and have been lucky to have received ongoing feedback from my Sensei.

Being committed is key, especially for an art such as calligraphy. Calligraphy is truthful and doesn’t lie: you only have one chance and a few breaths to do the brushwork. It is always a reflection of the artist’s state of mind. It makes calligraphy unique.

Recently I moved continents, from Asia to East-Africa. There is a very traditional artistic scene in this area, especially Maasai art and the tradition of East-African fabrics. No trace of calligraphy here, however. Japan and East-Africa are miles apart, not just geographically, but also in artistic tradition.

Where I am living now, resources are very limited. Practicing calligraphy requires specific paper, brushes, ink, and inkstone. Although ordering materials overseas is possible, it is difficult not to be able to feel the texture of the bristles of a brush, the surface of the paper.

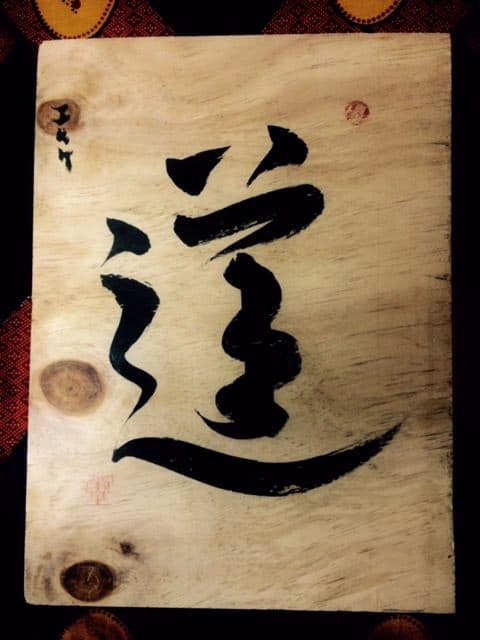

At first, this frustrated me. But then, I started thinking and trying to find new ways to get material. I walked around in town and saw wood workshops, tailors, meters and meters of beautiful fabric. Creativity is a state of mind. In the dusty East-African streets, the idea started to grow of trying to brush on different kinds of material: wood, canvas, cotton.

I got birch bark from a woodworker, canvas from a graphic design bureau, cotton from a fabric seller. I began brushing. I even brushed on the wall of my living room. Some things worked, others didn’t. I am still in the middle of experimenting. I also spoke to the old man who makes frames alongside the road. I trusted to him my calligraphy, and the next day he returned them to me, beautifully framed, all handmade.

My brushwork has become a crossover, first out of necessity, now because I really want it to. Just as Purism leads to narrow-mindedness in languages, arts, and architecture, this is also true in calligraphy.

I do not wish to compare myself to nor to criticize traditional Japanese Shodō (Zen) masters who have been practicing calligraphy in a very traditional manner. Shodō masters such as Shodo Harada or Yamada Mumon have been a great inspiration.

However, being in East-Africa has led to the insight that thinking out of the box, even for a very traditional art such as shodō, can lead to new inspiring dimensions. If you are technically skilled, new surfaces offer you the challenge that an artist is looking for. They also give the philosophical meaning of Zen phrases a contemporary and worldly dimension. Shodō can bring together and merge cultures and art forms.

More information about Elke Van dermijnsbrugge can be found at Studio Seicho www.studio-seicho.com